Inside Look: The Construction of NASA's Next Mars Rover

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

In May 2011, SPACE.com reporter Mike Wall visited NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., as scientists and engineers were wrapping up work on Curiosity, NASA's next Mars rover. With Curiosity's launch planned for Saturday (Nov. 26), this is his account.

It could be a scene from a James Bond film — a glimpse into the archvillain's lair.

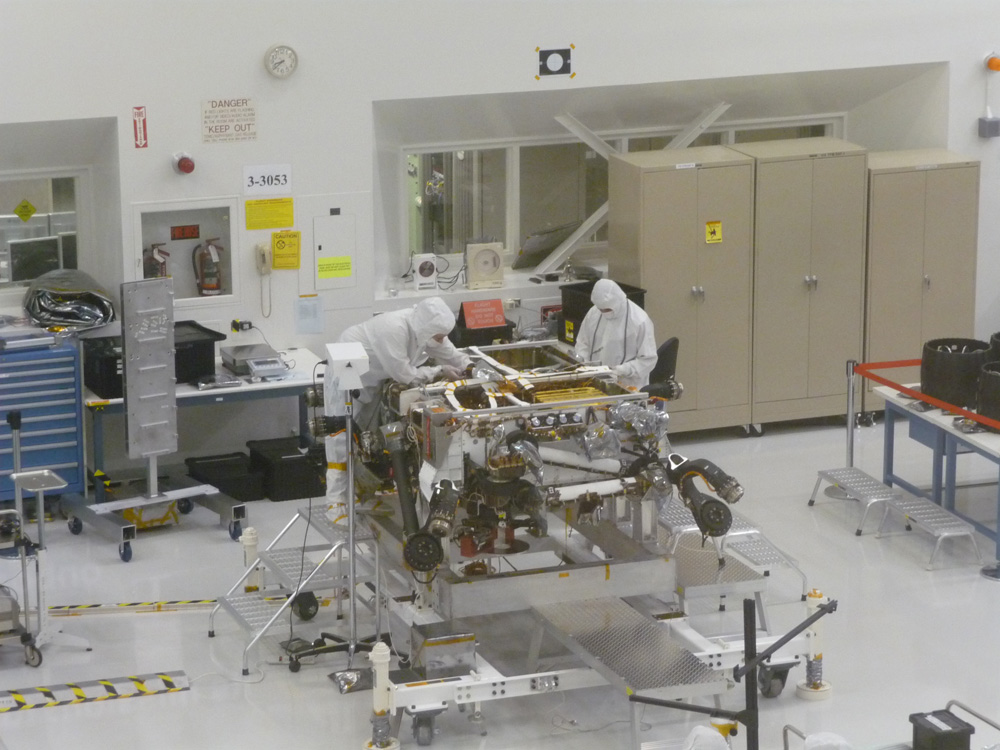

Anonymous white-clad workers, their faces obscured by surgical masks, cross a cavernous, high-ceilinged room. They pause to adjust or inspect large pieces of mysterious equipment, some of which is spangled with bright gold foil. It's obvious that they're building something complicated and important.

But they're not assembling a doomsday device, because this is no movie. The white-garbed technicians are employees at JPL, and they're putting the finishing touches on the space agency's next rover mission to Mars. This mission is called the Mars Science Laboratory, and the rover at the heart of it is a car-size robot named Curiosity.

I'm watching the technicians from a viewing gallery about 30 feet (9 meters) above a clean room at JPL's Spacecraft Assembly Facility in May 2011. JPL has been putting spaceships together for 50 years, so scenes like the one taking place below me are routine here.

But for me, taking all this in is a novel, surreal and thrilling experience. I'm looking at gear that, come next August, will be cruising around the surface of another planet. [Photos: NASA's Curiosity rover]

The next Mars rover, in pieces on the floor

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The $2.5 billion Mars Science Laboratory is slated to launch Saturday (Nov. 26) and drop Curiosity onto the Red Planet's surface in August 2012. The rover's primary task will be to assess whether Mars is, or ever was, capable of supporting microbial life.

Most of the pieces of the mission are laid out beneath me in the clean room.

"Do you know what you're looking at?" asks MSL project manager Pete Theisinger. Theisinger has agreed to meet and chat with me, as part of a larger tour I'm taking of JPL.

Theisinger guides me through the various MSL components, starting with Curiosity, which sits near the far wall. It's tough to peg the craft as a rover at the moment; it's been flipped onto its back, and its six wheels are off. Two technicians are elbow-deep in its electronic guts, reworking some of the rover's avionics and cabling.

Farther along the back wall, close to the room's right-rear corner, is MSL's cruise stage. This ring-shaped structure, about 13 feet (4 m) wide, will propel Curiosity and its associated parts through space to Mars, taking over where the mission's launch vehicle, an Atlas 5 rocket, leaves off.

A white-clad worker sits inside the ring, making some inscrutable check or adjustment. He, like the other technicians, wears a white mask and head-to-toe coveralls to minimize the chances of contaminating MSL with dust or microbes.

A new landing system

In front of the cruise stage, between it and the rover, sits the entry-descent-landing system. This is a novel and fantastic-seeming piece of technology — a rocket-powered sky crane that will lower Curiosity to the Martian surface on cables while hovering in mid-air.

Theisinger chuckles a bit when I say this sounds like something out of a sci-fi movie.

"I know, I know," he says. But he and the MSL team have faith in the system, which performed very well in full-up simulations.

"We're pretty confident that this will work," Theisinger says. "We've done everything that we know how to do" to test it. [Best (and Worst) Mars Landings of All Time]

Just in front of the cruise stage sits the backshell, a white, gumdrop-shaped structure that will encase the rover and landing system. The only MSL piece missing, aside from the launch vehicle, is the heat shield, which will protect the mission's components from the fiery temperatures experienced during entry into Mars' atmosphere. The heat shield is in Colorado at the moment, Theisinger says.

The work being done with Curiosity and other MSL parts consists of final tweaks and checks, to wrap up everything ahead of delivery to the Florida launch site, which occurred in late June.

Learning more about Curiosity

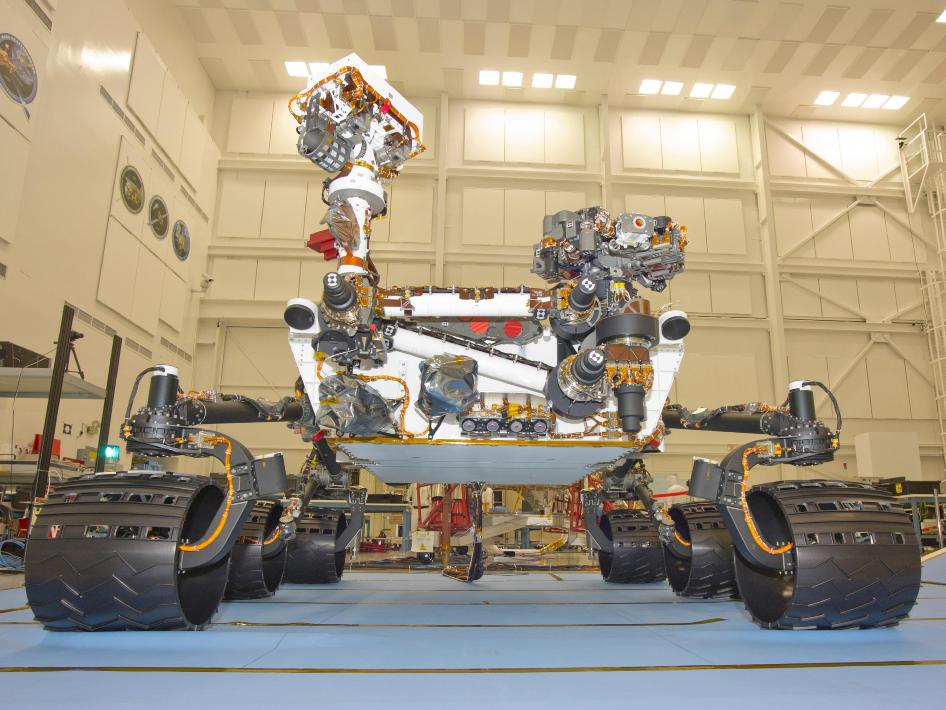

Curiosity is a big, burly rover that will allow scientists to learn much more about the Martian environment, both past and present. Curiosity weighs about 2,000 pounds (909 kilograms), compared to 375 pounds (170 kg) for each of its predecessors, the highly accomplished twin rovers Spirit and Opportunity.

Spirit and Opportunity landed on Mars in January 2004 to look for evidence of past water on Mars. They found a lot of it.

Curiosity will go a step further, assessing the Martian landscape for habitability during its planned two-year mission.

The rover will use 10 different science instruments to do this job, which will involve characterizing rock in minute detail and searching for organic molecules, among other tasks.

Curiosity boasts a five-jointed, 7-foot (2.1-m) robotic arm, which by itself weighs nearly half as much as Spirit or Opportunity. This arm will help in sample acquisition and analysis, and it has a drill that will be able to bore about 2 inches (5 centimeters) into Martian rock. No previous rover has had this deep-drilling ability, and the MSL team is pretty pumped about it.

"For geologists that study rocks, there's nothing better than getting inside," MSL deputy project scientist Joy Crisp told me, after I'd said goodbye to Theisinger and the clean room. During our meeting, she gave me in-depth information on Curiosity's science payload and objectives.

I also met with JPL's Kevin Burke, who has led much of the work in developing the tools on Curiosity's arm. Burke described the processes involved in designing, building and testing such a complex suite of equipment, which must work perfectly together on the frigid surface of an alien planet.

Burke also talked about some late re-work that had just been done on the drill's force sensor, which tells the rover how hard it's pressing on the drill.

It was a fascinating day. When I left JPL, my head was full of facts, diagrams and visions of Curiosity roving about the Martian surface. Burke said I should come back to JPL to watch MSL's landing in August. I've already got it circled on my calendar.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall.Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcomand on Facebook

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.