Vibrating Glove May Give Helping Hand to Astronauts & Surgeons

No, it's not a sex toy — it's better. A new vibrating glove not only boosts the sensitivity of human fingertips, but also enhances hand coordination. That may someday help space-suited NASA astronauts work well with their hands during marathon spacewalks or aid neurosurgeons during delicate operations.

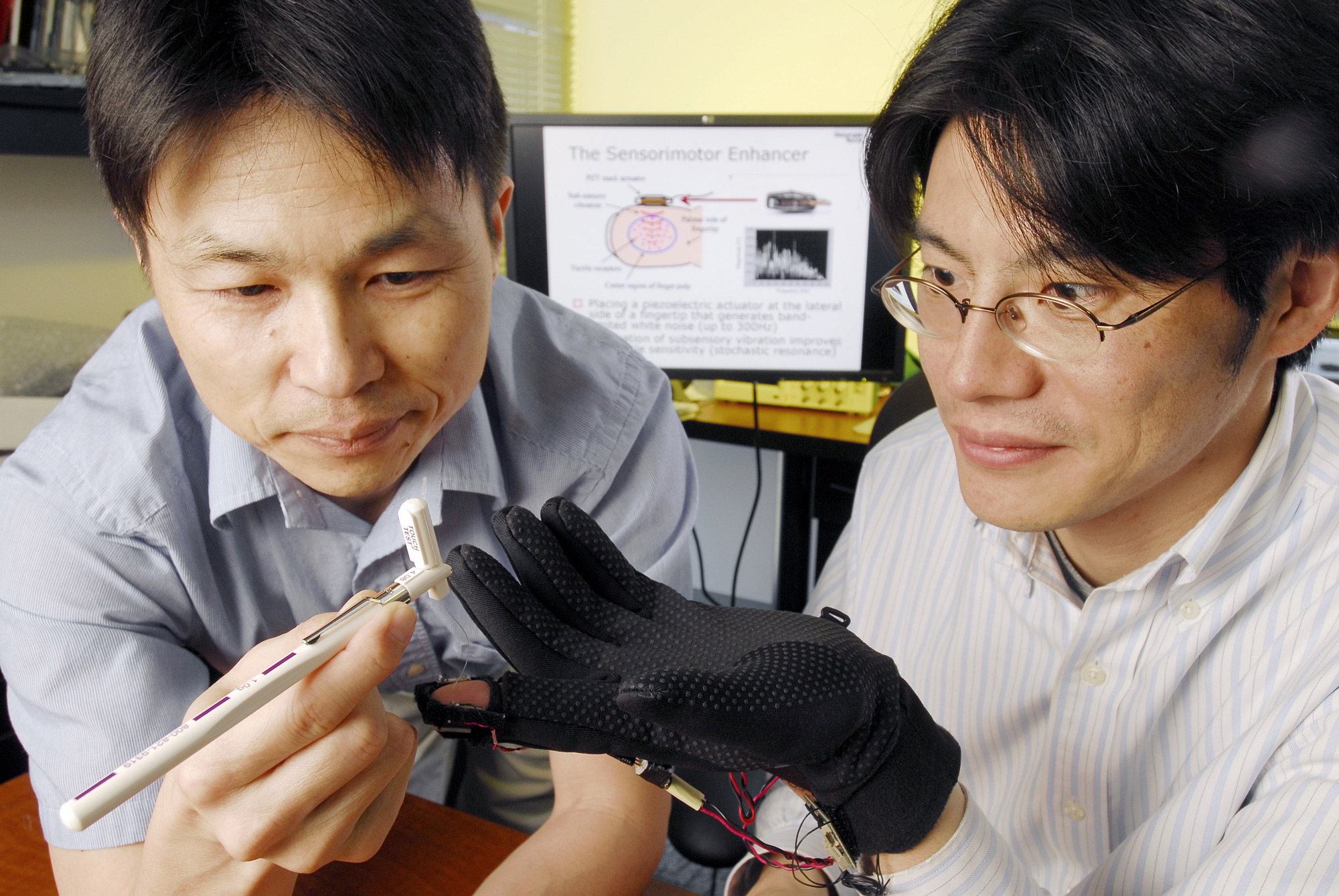

Scientists have known for decades that faint vibrations can make fingertips hypersensitive. But recent tests with the handy new glove have shown the connection between having a better sense of touch and having more nimble fingers, said Jun Ueda, an assistant professor in mechanical engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta.

"It can be used in any case where you want to wear gloves but don't want to lose your sense of touch," Ueda said. "And it's not limited to that application. What we're seeing are possible benefits for precise assembly tasks, such as when astronauts use a space tool during a spacewalk."

U.S. military members ranging from soldiers to jet fighter pilots could benefit from such gloves during combat. Similarly, fishermen or oil rig workers might also make use of the enhanced manual skills when working in rough, cold environments. [Infographic: Spacesuit Fashion Through the Years]

Filling up the glass

The gloves might also help school kids with their handwriting.

"What I'm thinking is we may be able to help small kids with their handwriting skills, by helping them manipulate pencils or pens accurately so that they can make nice graphics or letters," Ueda told InnovationNewsDaily.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Such enhancement is possible because of how the human sense of touch works. Nerves in our fingertips get triggered once outside stimuli reach a certain threshold — a bit like how water fills up a glass until it overflows. Faint "white noise" vibrations can partially fill the metaphorical glass and make it easier for smaller stimuli to trigger fingertip nerves.

The vibrations boosted performance during sensitivity tests for 10 volunteers, who wore the gloves with their non-dominant index fingers exposed. Tests included sensing when two points were touching their finger as opposed to one, sensing the weights of different fiber strands pressed against their fingers, and blindly feeling pieces of sandpaper to match them to another piece.

But the biggest challenge came when each person pinched and held an object for three seconds with as small a force as possible without letting it slip. Each person did better on the tests during several vibration levels, even at 50 percent below the level where they could sense the vibrations.

From humans to robots

Improved performances of 15 to 20 percent on such tests may sound small, but still stood out as statistically significant. Ueda and his colleagues hope to fine-tune the glove design and also figure out the level of vibration related to the greatest benefits. [Astronauts in Space to Explore Earth with Robots]

The glove might even someday help humans to remotely control robots, if the glove's movements are wirelessly transmitted to a robot's equivalent of hands. The added sensitivity and coordination could give the human operator more skill in controlling the robot hands — especially if vibrational feedback in the glove simulates the resistance of an object that the robot might pick up or handle.

"What we could do is artificially amplify the force by a factor of two or three and give the amplified force to the operator," Ueda said. "Another strategy is that it might be OK to give the same amount of force, if the operator has better sensitivity by using our device."

For now, Ueda wants to make sure that the device can work when a person's fingertip is covered by the glove, as would be the case in most real-life situations. But his group has already begun considering proposals for either NASA or the U.S. Department of Defense.

You can follow InnovationNewsDaily Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.