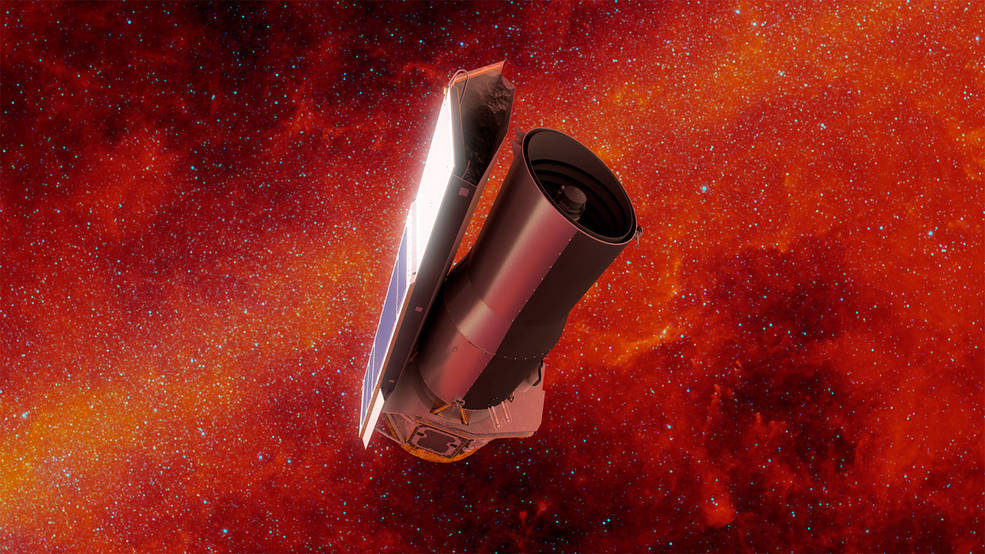

Farewell, Spitzer Space Telescope! NASA shuts down prolific observatory.

It saw light that humanity could never see.

One of NASA's great telescopes will go offline today (Jan. 30) after 16.5 years of observations that helped to paint a more complete picture of the universe.

The Spitzer Space Telescope launched in 2003 to look at the universe in the infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum, allowing scientists to view objects that are cooler than the stars that emit visible light. Spitzer could view the structure of galaxies and also expanded on its original mission by watching a variety of cosmic objects, like the Earth-size TRAPPIST-1 rocky exoplanets, a nearly invisible ring around Saturn and a comet that was struck by a spacecraft.

Human eyes can naturally sense starlight, but sometimes we need specialized tools that can view our world through other parts of the light spectrum, allowing us to learn more than what meets the eye. "The advances we make across many areas in astrophysics in the future will be because of Spitzer's extraordinary legacy," Paul Hertz, director of astrophysics at NASA said in a NASA statement about the mission.

Related: Spitzer's greatest exoplanet discoveries of all time

More: The infrared universe seen by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope

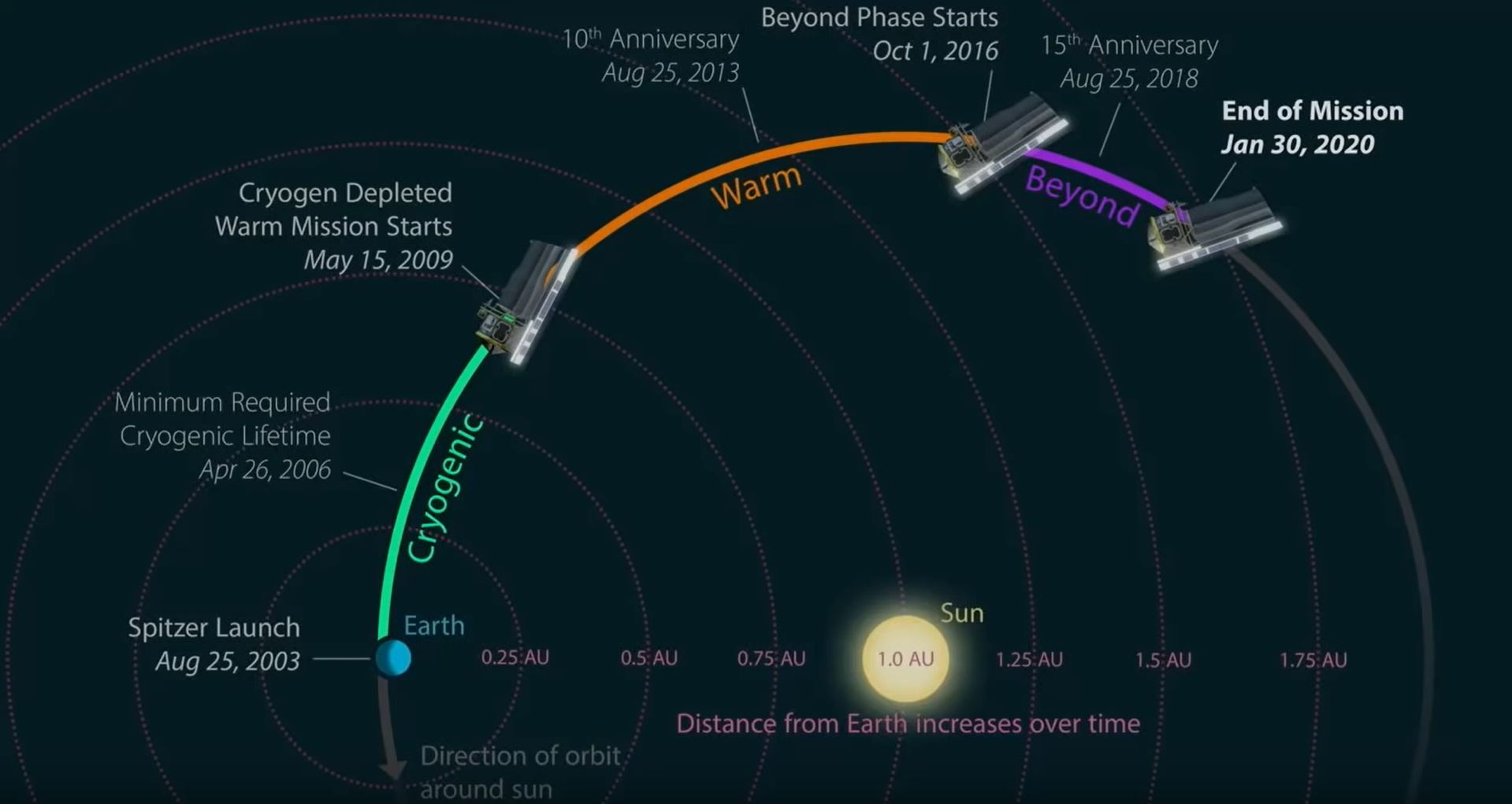

Spitzer's science activity came to an end yesterday (Jan. 29) and its mission team will put the spacecraft into a permanent hibernation mode today (Jan. 30). After the final command, Spitzer will continue its trajectory that takes it farther away from the Earth over time, where team members think it will eventually crash into a debris field, according to mission team remarks during NASA's Jan. 22 news conference.

Spitzer made its observations using a technique called spectroscopy, which scientists can use to measure the chemical composition of dust to learn what the universe's ingredients are like.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Spitzer's former Project Manager Suzanne Dodd said in a Jan. 23 panel about the telescope that Spitzer uncovered a "cornucopia" of cosmic details. Much of its work dealt with interstellar dust, which cocoons baby stars, provides the building blocks for planets and creates the invisible skeleton of galaxies across the universe.

"Dust are these clouds of soot that fill the interstellar medium and can completely block our view of the center of our galaxy and the more distant parts," Robert Hurt, Spitzer imaging scientist, said during the panel. "Dust has a very interesting property that as you go to longer wavelengths of light, that light starts to be able to move through the dust … to the point that it becomes virtually transparent."

In the shorter infrared wavelengths, dust can glow because stars can heat up the frigid material to a slightly warmer temperature. Spitzer could observe very cold objects that are just slightly above absolute zero, which allowed scientists to get a better idea of an environment far, far away.

"Being able to see the dust as a glowing element, we can now see those spiral arms [of a galaxy] as the skeleton in an X-ray of an animal, where the dust is building up as ridges and lanes and spokes, Hurt said. "These are tied to the processes that flows through a galaxy and builds up and creates dense regions of star formation."

Spitzer helped reveal that galaxies in the early universe were heavier than scientists expected, deepening their understanding of how galaxies evolve over time, according to the NASA statement.

The mission's scientific output relied on the spacecraft's location. "The key to Spitzer's success is it's novel orbit," Dodd said in the panel event. "It's in an Earth-trailing orbit, which means once it's launched, it's in the same orbit as the Earth around the sun but it just drifts away slowly."

To view the universe in infrared, Spitzer had to be cool enough to not emit heat and far enough away from Earth in order to get a good view without interference from the infrared environment around our planet and the moon.

But the mission wasn't designed to work for 16 years or at its current distance from Earth. "The team has had to adapt year after year to keep the spacecraft operating," Joseph Hunt, Spitzer project manager, said in the NASA statement. "But I think overcoming that challenge has given people a great sense of pride in the mission. This mission stays with you."

Spitzer's now-former observatory colleagues, the Hubble Space Telescope and the Chandra X-ray Observatory, are still watching the universe. Hubble will celebrate its 30th anniversary this year.

- With end in sight, Spitzer Space Telescope releases glorious nebula images

- Swan nebula 'star factory' reveals protostar treasure to NASA's flying telescope

- Tour the colorful Crab Nebula with this stunning new 3D visualization

Follow Doris Elin Urrutia on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.