Satellite megaconstellations will mar astronomers' view of heavens, study finds

The impact will be greatest on telescopes with wide-field views.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

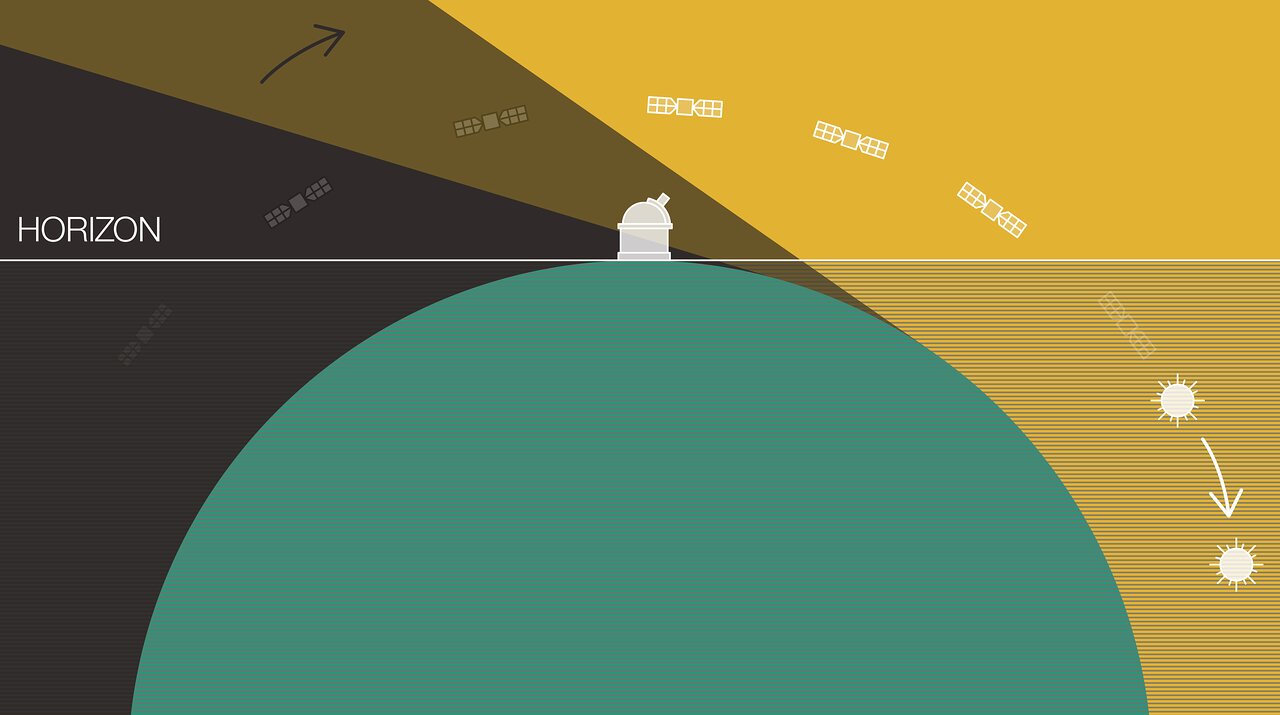

Two European Southern Observatory (ESO) telescopes will be "moderately affected" in their observations by the rise of big, new satellite constellations like SpaceX's Starlink and Amazon's Project Kuiper, a new study finds, while wide-field telescopes will be "severely affected."

While the study covers multiple observatories, it centers on two flagships of ESO – the operational Very Large Telescope (VLT) and the forthcoming Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) — that perform (or will perform) broad studies of exoplanets, stars and galaxies.

Long exposures at twilight of around 16 minutes could see roughly 3% of their observations "ruined," the study team found, while shorter exposures would see about 0.5% of observations hurt by satellites. Dark-night observations would be less affected, as the satellites would be in shadow.

Related: In Photos: SpaceX launches 60 Starlink satellites to orbit

These ground observatories are important for astronomy, as they can provide a higher resolution than space observatories, such as NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, and can be more easily upgraded. But their pristine, dark-sky views in Chile will be threatened as more satellites clutter the sky, ESO officials said.

Companies such as SpaceX and Amazon plan to launch thousands of satellites to build out their internet-beaming constellations, and these machines will be regularly crossing the sky and occasionally blotting out cosmic views. The International Astronomical Union is among the professional groups warning about how these constellations could impact astronomy, meaning ESO is adding its voice to those of a growing group of concerned astronomers.

Another category of observations facing a threat is wide-field views, which capture a large portion of the sky at one time. For example, the U.S. National Science Foundation's Vera C. Rubin Observatory could see between 30% and 50% of its exposures marred by satellite streaks, ESO officials said. One of Rubin's mandates is to seek out asteroids that may pose a threat to Earth, which would be more difficult to do under the new circumstances, the organization added.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Because of their unique capability to generate very large data sets and to find observation targets for many other observatories, astronomy communities and funding agencies in Europe and elsewhere have ranked wide-field survey telescopes as a top priority for future developments in astronomy," ESO officials said in a statement.

The new ESO study assumes an orbital population of 26,000 operational constellation satellites. About 250 of these craft will be above big scopes like the VLT at any given time in the zone where astronomical observations typically take place, at 30 degrees or more above the horizon. A naked-eye observer, not using a telescope or binoculars, would likely be able to see up to 100 at a time, 10 of which would be more than 30 degrees above the horizon, ESO officials said.

For perspective, there are currently about 2,200 operational satellites orbiting Earth, along with a lot of space junk.

But steps can be taken to reduce the impact of the coming megaconstellations, ESO officials said.

"Depending on the science case, the impacts could be lessened by making changes to the operating schedules of ESO telescopes, though these changes come at a cost," ESO officials said in a statement. "On the industry side, an effective step to mitigate impacts would be to darken the satellites."

SpaceX is testing a coating that is supposed to lessen the glare of its Starlink satellites, 300 of which are already up. And that number is just the beginning; the company already has approval to loft 12,000 Starlink satellites and has applied for permission to launch about 30,000 more.

SpaceX founder and CEO Elon Musk has expressed confidence that Starlink won't unduly affect astronomy efforts, despite the current concerns. The satellites get much dimmer as they climb to their operational orbits, he said, stressing that much of the worry has stemmed from observations of recently deployed Starlink craft flying low and in formation.

"I am confident that we will not cause any impact in astronomical discoveries. Zero," Musk said Monday (March 9) during a keynote conversation at the Satellite 2020 conference in Washington, D.C. "We'll take corrective action if it's above zero."

A study based on the research will appear in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics and is available in preprint version on ESO's website.

- Why SpaceX's Starlink satellites caught astronomers off guard

- 10 space discoveries by the European Southern Observatory

- SpaceX's 1st Starlink satellite megaconstellation launch in photos

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.