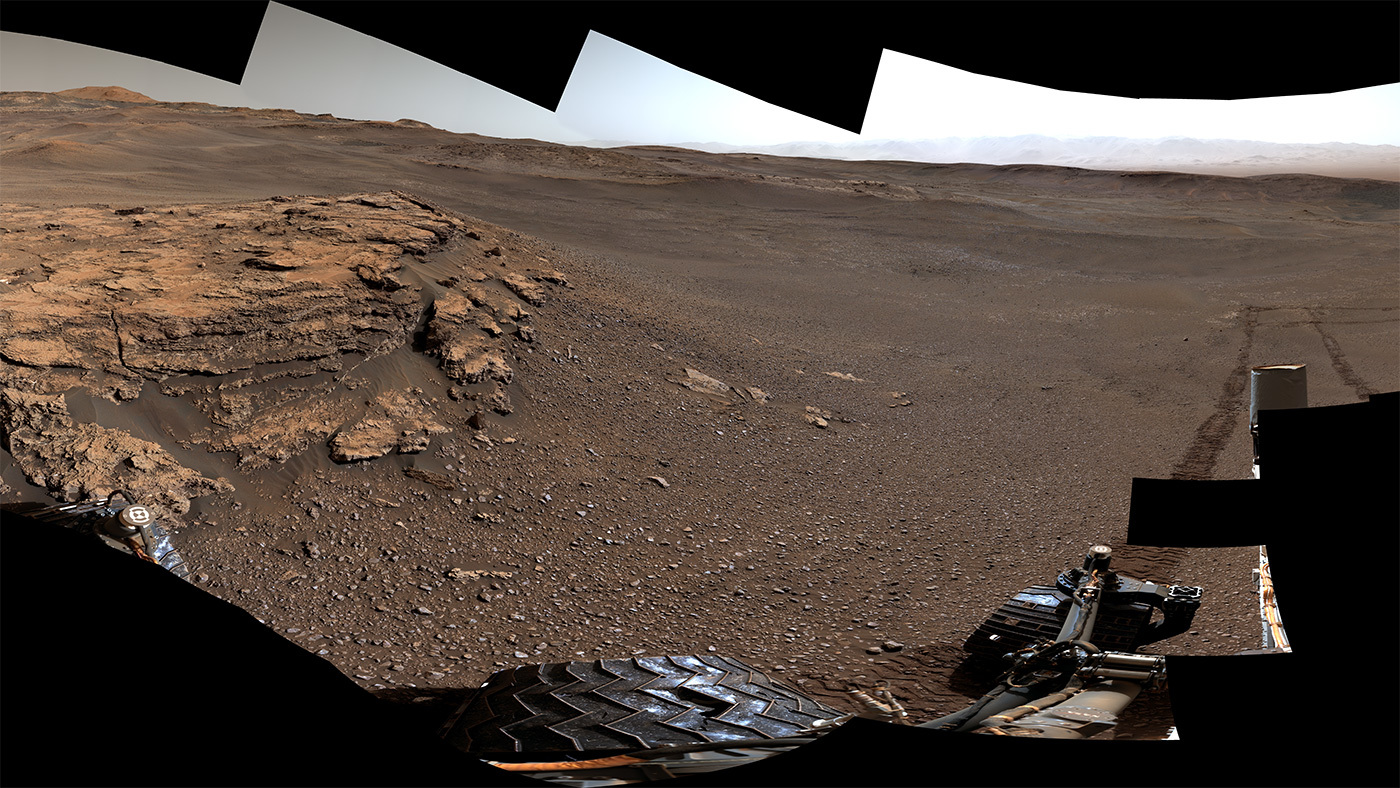

Martian Merlot? How a Red Wine Compound May Help Us Cope with Mars' Gravity

Resveratrol is found in peanuts, chocolate and blueberries, too.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A plant compound found in chocolate, peanuts, blueberries, grapes and wine may be a great supplement for future spacefarers wanting to maintain their bone and muscle health after leaving Earth — and its gravity — behind to reach Mars.

Marie Mortreux is the lead researcher of a new study looking at the effects of this antioxidant, known as resveratrol, on rats exposed to simulated Martian gravity.

While there's been quite a bit of research conducted over the last five decades about the effects that microgravity can have on the human body, the potential effects of Martian gravity, roughly 40% of Earth's gravity, on terrestrial lifeforms like the human body "remain less well understood," according to Mortreux and her colleagues in a recent paper.

Related: Wine on Mars? World's Oldest Wine-Making Country Wants to Make It Happen

Mortreux is a post-doctoral research fellow at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) at Harvard Medical School in Boston. She worked in the lab of Seward Rutkove, Chief of the Division of Neuromuscular Disease in the Department of Neurology at BIDMC, who also co-authored a 2013 study that looked at the effects of microgravity on mice flown into space aboard the shuttle mission STS-135. When NASA awarded Rutkove a grant for this current research, he selected Mortreux to lead the new research on how Martian gravity would affect rats and whether doses of resveratrol would help counter the deteriorative effects of reduced gravity, Mortreux told Space.com.

Rodents aren't the only creatures that have been put to the test for the sake of understanding what Mars might do. The 2015 Twins Study looked at how astronaut Scott Kelly's body changed compared to that of his twin brother, astronaut Mark Kelly, who remained on Earth's surface as a control during the nearly year-long study.

Evolution selects for the best qualities that make an animal thrive in its environment. For creatures that fly, bones have evolved to be delicate (like bats) or hollow (like birds). For animals that live in the depths of the ocean, bioluminescence is a valuable trait. And for terrestrial animals like humans, our skeletomuscular system evolved to perform under 1g of gravity, the average acceleration pushing down at sea level. When 300,000 years of homo sapien conditioning get upended by putting our bodies in space, they quickly adjust, but the lack of Earth's gravity can take a toll on our health.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

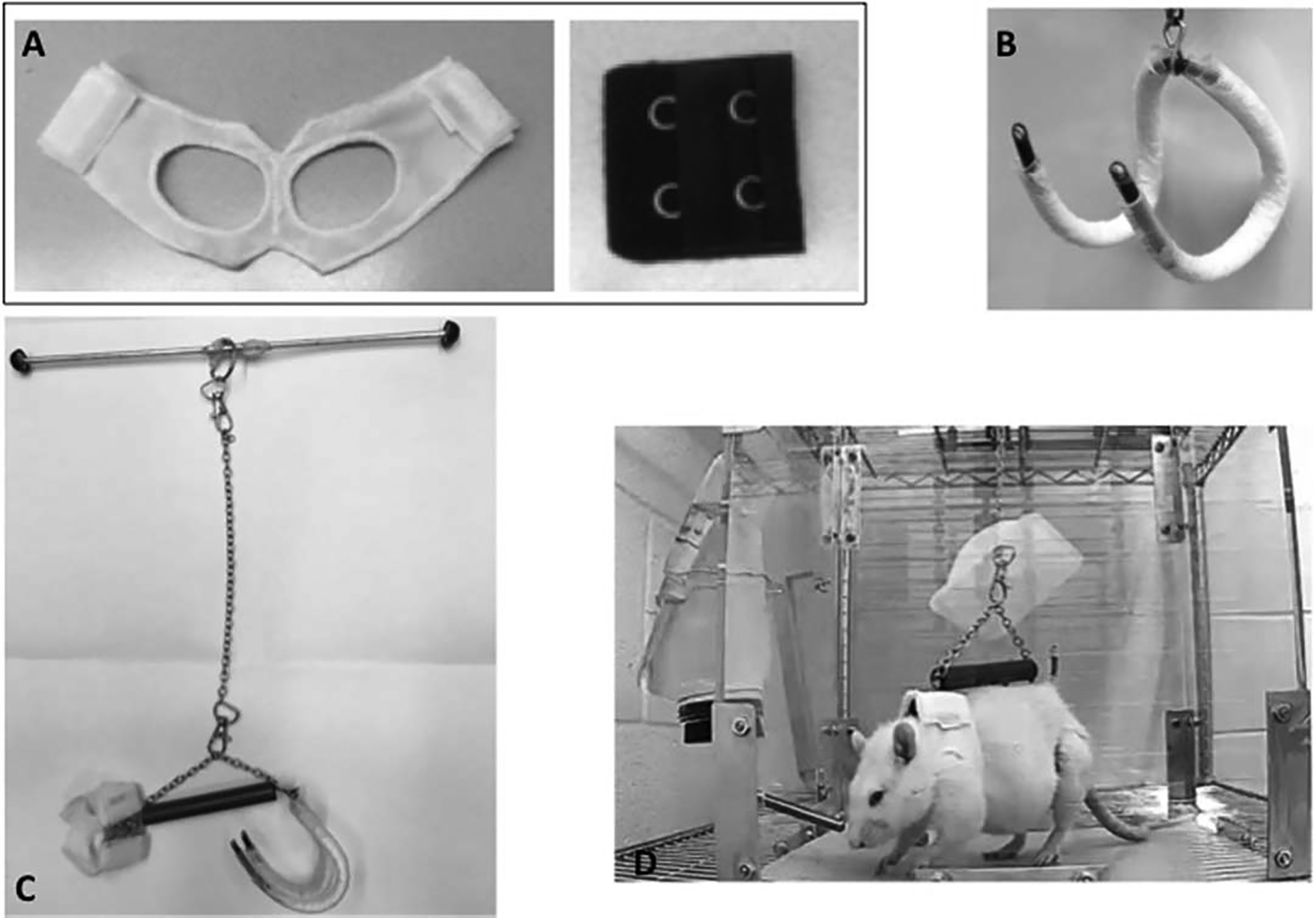

To investigate how resveratrol might help human bodies adapt better for long-duration missions to Mars, Mortreux put them into special apparatuses.

"Basically my rats [were] secured in a jacket, in a pelvic harness. They were suspended from the top of their cage, and by adjusting the length, I can adjust how much they are weighing on the floor. So, if my rat weighs normally 400 grams (.88 lbs) when it's at 0.4g... he's only bearing 40% of his body weight. This is what we call the Martian gravity analog," Mortreux told Space.com.

Then the 24 rats were split into two groups and both sets were exposed to Martian gravity for 14 days. One group was given daily doses of resveratrol, with their first dosage coming in on the same day they experienced mock Martian gravity.

Once the 14-day period was up, the researchers euthanized the rats and measured the mass of their triceps surae, the pair of muscles located at the calf. The rats who received resveratrol maintained more of their muscle density and mass than the control group.

Mortreux unexpectedly became involved in this space-related work, she told Space.com. "I have to say, I love space but I never imagined myself being a space scientist when I was doing my Ph.D, and I became one and I am very glad I did."

The paper detailing Mortreux's work was published July 18 in the journal Frontiers in Physiology.

- Forget Space Beer, Order Meteorite Wine Instead

- A Brief History of Mars Missions

- Mars Explorers Will Tackle Radiation, Depression … and Space Bread

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.