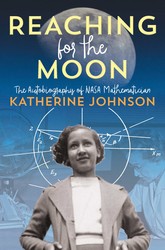

Reaching for the Moon: Exclusive Excerpt from Katherine Johnson Autobiography for Kids

In the early 1950s, Katherine Johnson was thrilled to join the organization that would become NASA. As a mathematician, she worked on many of NASA's biggest projects including the Apollo 11 mission that landed the first men on the moon.

Johnson's work was critical to the success of many of their initiatives, including the Apollo lunar landing program and the start of the space shuttle program. Throughout her long career she has received numerous awards, including the nation’s highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, from President Barack Obama. Additionally, one day before her 100th birthday, West Virginia State University unveiled a new statue of her along with a scholarship in her name. In May 2018, Mattel released a Barbie doll in Katherine’s likeness as part of their "Inspiring Women" line.

And in July, Johnson is releasing an autobiography, "Reaching for the Moon" (Athenium Books for Young Readers, 2019), chronicling her life and her groundbreaking work at NASA for an audience of young readers aged 10 and up. Read an exclusive excerpt from Chapter 5 of "Reaching for the Moon" below about Johnson's first days at NACA, the predecessor to NASA.

Related: Best Kids' Space Books

Excerpt from "Reaching for the Moon" Chapter 5

The night before my first day of work at NACA, I touched up my navy-blue tweed pleated skirt and jacket and checked my stockings to make sure they didn't have any runs. I woke up the next morning without an alarm clock, excited and a little nervous. I sensed that my life was about to change.

"What secret project do you think the government will have me working on?" I wondered aloud to Jimmie, who lay awake in bed alongside me.

"I don't know, honey, but I know it will be important."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I guess I'll have to wait to find out!"

When I arrived at Langley later that morning, I discovered that since I had a bachelor's degree in mathematics, I would be hired as a mathematician. Women whose degrees were in other disciplines were hired to be what were called computers.

I was to report to a branch called West Area Computing and would be on probation for six months.

"Don't come in here in two weeks asking for a transfer," the human resources director told me.

"This is just my first day," I replied, taken aback. "I'm not sure why anyone would do that."

I didn't appreciate her comment, but there was a tightrope I needed to walk. I was really excited about this job — and as a mathematician I would be getting paid three times as much as I'd been paid as a teacher.

Related: How 'Hidden Figures' Came Together: Interview with Author Margot Shetterly

My heart beat with excitement as a woman led me over to the Aircraft Loads Building. Then she opened a door and ushered me in.

As I stepped into the room, I witnessed something that I'd never seen before: a couple of dozen Colored women sitting at desks, typing on Monroe or Friden desktop calculating machines.

What an amazing sight!

I stood there astounded. All of the women were neatly dressed in blouses and jackets and skirts. Back then a room filled with so many professional Colored women was a rare sight. And not one of them was a teacher or a nurse, the professions that were most common for Colored career women. Nor were any of them domestics, the job so many Colored women worked in back then.

These were the highly regarded computers I'd been hearing about. The click, click, click of their fingers running across the ten-by-ten gray manual keyboards of their calculators resonated throughout the room. Long before the electronic device we now know as a computer came into being, "computer" was the job title given to the women who performed mathematical calculations for Langley's engineers. I knew that the engineers were all men; the computers were all women. Most were White; a smaller number were Colored. I'd learn that all of us were known as computers with skirts.

"Katherine?" A familiar voice from behind me brought me out of my reverie.

I turned around to a smiling woman whose right hand was outstretched — the same woman I'd met back in White Sulphur and whose daughter had often sat on my parents' front porch.

"Dot?"

"Oh, what a small world!" She laughed.

"My goodness! I've heard so many amazing things about you, but had no idea that the person I've been hearing about was you," I said, recalling our days back in White Sulphur when the girls were little. "I'm thrilled to be here and am ready to work."

Before long, I'd learn that Mrs. Vaughan, as I called her at work, was an honors graduate of Wilberforce University with a degree in math. She had been recruited to Langley in 1943 from Farmville, Virginia, where she had been working as a math teacher. She arrived believing she was accepting a temporary job; however, her work had become so highly respected that not only was she still at Langley years later, but in 1949, she had been promoted to acting head of the group. In 1951 she became one of NACA's first women section heads as well as the base's only Colored manager.

A White woman, Margery Hannah, was the head of West Computing and was Dorothy's boss.

It soon became clear that Dorothy was highly respected by both White people and Colored people. I'd discover that both her work and the work of the West computers was admiringly regarded all over the Lab. And she moved with an authority that I had rarely seen in other Colored women, who were usually required to fill subservient roles. Mrs. Vaughan was accustomed to being in charge.

Each day as they came into our office, I observed that the White male engineers really relied on her to recommend the best computers for each particular job. If she could come from a small town, as I had, to Langley and excel, I was certain that I could too. Dorothy Vaughan was incredibly knowledgeable. She was very impressive; I found her presence inspiring.

The first assignments Mrs. Vaughan gave me involved working with engineers focused on airplane aeronautics. Aeronautics includes the science and practical issues associated with building and flying airplanes. During that era our nation was focused on the goal of supersonic flight, which means that the speed of the airplane is faster than the speed of sound. That's pretty fast. Sound travels at 768 miles per hour. Whenever a plane travels that fast, it creates a shock wave called a sonic boom that sounds like a loud clap of thunder. The base was also creating experimental planes with new shapes that allowed them to fly faster and faster. As the Cold War continued, NACA focused on designing missile warheads. People were also starting to talk about the first humans flying to outer space.

The engineers' job was to come up with the theories and formulas that advanced the nation's aviation know-how; the computers performed and checked calculations to ensure that the engineers' ideas worked. Back then there was a widespread belief that men were just not interested in the small things. They didn't care how you did the work, they would just say, "Give me the answer." It was believed that women would be more attentive to the fine details; men wouldn't have the patience to do that.

If the men's ideas didn't work, the planes wouldn't fly, so the women's work was absolutely essential. Later, I would learn that the women of West Computing could type ten digits at a time into their calculators from memory.

Right away I loved my new job. Suddenly I was using the advanced theorems and skills I'd learned from Dr. Evans and Dr. Claytor. I could immediately see how well they'd prepared me. My class on the math of outer space came in especially handy.

Each morning, I'd get up, unfasten the bobby pins that held my pin curls in place, and get dressed. Then I'd awaken the girls and we'd eat breakfast — usually fruit, cereal, toast, and maybe homemade apple sauce. After that, we were off to work and school.

My neighbor Eunice Smith, a West computer who lived three blocks over, would pick me up, and she, Alta Brooks (another computer), and I would rush to the office together. The environment at Langley was so stimulating; it was exciting; it challenged every bit of my brain! It was a pleasure to do work that produced results that were so important to the engineers. But even though some of my work is famous today, back then I had no idea that it would one day be important or known the whole world over.

The West Computers were extremely committed to our assignments. We did a good job, worked a full day, and fulfilled our responsibilities; that was our mantra. We felt proud to be representing the Colored community in supporting our nation, especially in the face of the threats posed by the Russians.

At NACA, I didn't feel segregation in quite the same oppressive way that I did out in the world. Though there were Colored bathrooms and a Colored section of the cafeteria, I usually ate at my desk. Margery Hannah treated us well, and I spent lots of time working with or for White men and women, which was different from what was happening throughout much of the South. We had a mission and we worked on it. What was important was to do your job.

Of course, at the end of the day, segregation dictated that we went home to separate communities, our children attended separate schools, we worshipped in separate churches — we even shopped for clothes in different places and went to different grocery stores.

But the next day we'd arrive at Langley and come together to do our jobs all over again.

Related: 'Hidden Figures' Explores NASA and Civil Rights History

Now, when I first reported to the branch, the men would just hand me work and tell me they needed me to make calculations. Back then women were supposed to stay in their place. Lots of people — both men and women — believed that women were too emotional and that we should stay home and raise the children and leave all the thinking and working up to men. Of course, this belief system was less common among Colored families, since we weren't allowed to have the best jobs. Colored women were very poorly paid, and so were our husbands. Our families needed women's income in order to survive, so as a result most of us worked. Still, in the workforce, women were to stay in their place.

About two weeks into my new job, a man burst into the office, seemingly in a hurry.

"I need two Colored computers," he stated over the din of the typing.

There was a specific reason that he'd come to West Computing as opposed to East Computing, where the White computers worked. The hurdle for White women computers to be hired was lower than it was for Colored women. Indeed, many of them were the engineers' wives. White women could get hired without having a college degree. Colored women were not only required to have a college degree, ideally in math, but they also had to have a high GPA. In fact, NACA recruited Colored students who had earned honors in math.

Dorothy pointed at me and another woman and said, "Katherine, Erma."

Erma Walker was one of my peers, and boy, she was sharp! Mrs. Vaughan knew that our educational backgrounds and skills matched what that engineer's department was looking for. Later I'd learn that Erma's husband, Cartwright, worked with Jimmie at the shipyard.

We grabbed our purses and lunch bags, then followed the man over to the Maneuver Loads Branch of the Flight Research Division, where we were then assigned to an all-male research team. We were given desks near each other and were each given a calculating machine.

When I sat down, the engineers sitting next to me got up and walked away. I wasn't sure why. Was it because I was Colored? A woman? Something else? There was no way to know for sure, but I found it amusing. Eventually, we became good friends.

One of the engineers wanted to me to help him analyze some data from a flight test. I was to look through his long calculation sheets and compute an answer for him. That was my job, so I would do it to the best of my ability.

I pulled out my graph paper and my French curves, which would help me draw curves of different radii. But as I double-checked the engineer's math, I saw something unexpected. The calculation didn't look right. I soon discovered that he'd made an error involving a square root.

I thought for a moment about how to approach the situation. It would be unusual for a Colored person to question a White person. I knew that in some situations questioning White people could be quite dangerous. We learned to pick our battles for the greater good and let other things go by the wayside. It was also unusual for a woman to question a man. Back then most women just did what they were told to do. They didn't ask questions or take the task any further.

But if you want to know the answer to something, you have to ask a question. Always remember that there's no such thing as a dumb question except if it goes unasked. Girls and women are capable of doing everything that boys and men are capable of doing. And sometimes we have more imagination than they do.

Knowing this, I took a deep breath before I spoke. "Is it possible you could have a mistake in your formula?"

Now, if the wind tunnels hadn't been running in the background, with their constant whoosh and roar, I might have heard a pin drop in the room.

I'd crossed a social line, and everyone froze. I could almost hear some of the engineers thinking, Who is she, a Colored woman, to question a White male engineer?

The man came over to my desk and looked over my shoulder.

"I could have made a mistake," he said, "but we've been using that formula for years."

"I understand that, sir. I just think that it's inaccurate."

His face began to turn the color of a cherry cough drop.

I was right and he knew it.

Before long it became clear to the men that I'd studied a high level of math known as analytic geometry. Very few men, not to mention women, excelled in that type of math. When I finished that project, I expected to be sent back to West Computing so that Mrs. Vaughn could assign me to the next project, as was the normal protocol.

To my surprise, that never happened. Somehow the engineers "forgot" to return me. Instead they just handed me the next set of calculations—and then the next. Then the next. Then the next. That's when I realized that they needed me, Colored or a woman or not.

And suddenly I found myself a research mathematician! I was no better than anyone else, but no one was any better than me.

Every time engineers would hand me their equations to evaluate, I would do more than what they'd asked. I'd try to think beyond their equations. To ensure that I'd get the answer right, I needed to understand the thinking behind their choices and decisions. I started asking them "how" and "why."

At first they were surprised. So were Erma and the other Colored computers who occasionally worked with me in that department. Back then men — especially those in prestigious careers — expected that women would not question them.

A couple of the guys looked at me like I should mind my business. Who was I to be doubting them? I was Colored. I was a female. They were both men and engineers.

But I was good at what I did, and I wasn't doubting them; I was being curious. Eventually they'd answer.

Then after a while, in addition to "why," I also started asking "why not" so that I could get to the root of the question.

I didn't allow their side-eyes and annoyed looks to intimidate or stop me. I also would persist even if I thought I was being ignored. If I encountered something I didn't understand, I'd just ask. And I kept asking no matter whose calculations I was evaluating — an engineer's or the head of the entire department.

Having enough information to do my work accurately was essential, so I just ignored the social customs that told me to stay in my place. I would keep asking questions until I was satisfied with the results. Before long the guys began to understand the contribution that I was able to make when I had the answers to the questions that allowed me to think on their level. Quietly the quality of my contribution began to outweigh the arbitrary laws of racial segregation and the dictates that held back my gender.

In this building there was no Colored bathroom, so I just went to the women's room that was there. (Eventually I was someplace at Langley where there was a Colored bathroom, but I refused to use it, and nobody had the nerve to say anything.) I stopped going to the cafeteria altogether. It was too far, so I just ate at my desk. After a while, at lunchtime I began to play bridge with the engineers I worked with.

After my six-month probation, I got a promotion, a raise, and an offer to permanently join the Flight Research Division's Maneuver Loads Branch, whose research included keeping aircraft safe when they were in flight.

Shortly thereafter they assigned me to help solve the mysterious plane crash of a small Piper plane that seemed to have just dropped out the sky on a clear blue day. For months I studied and plotted the data from the plane's flight recorder, noting the plane's altitude, speed, acceleration, and so on, measured during the flight. Eventually the engineers ran a simulation. I analyzed that data as well. My research helped uncover the fact that the plane had flown perpendicularly across the path of a jet that had just gone by. The engineers already knew that swirls of atmospheric wind disturbance, known as wake turbulence, form behind a plane as it flies through the air and can last for as long as half an hour. But what they hadn't known and discovered with the help of my analysis was that the forces associated with wake turbulence can be so great that they can somersault a plane out of the sky. Our research resulted in changes to air-traffic regulations, requiring planes to fly no less than a certain distance apart.

By then the guys were no longer bothered by my questions. They were thrilled that I, too, read Aviation Week and was as interested in these problems as they were. Some of the guys eventually became my good friends.

I truly loved going to work every single day — and when you love what you do, it doesn't feel like work!

- 'Hidden Figures' Showcases Perseverance of Black Women at NASA

- Here's How Katherine Johnson Got to the Oscars — With an Astronaut's Help

- On 'Hidden Figures' Set, NASA's Early Years Take Center Stage

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.