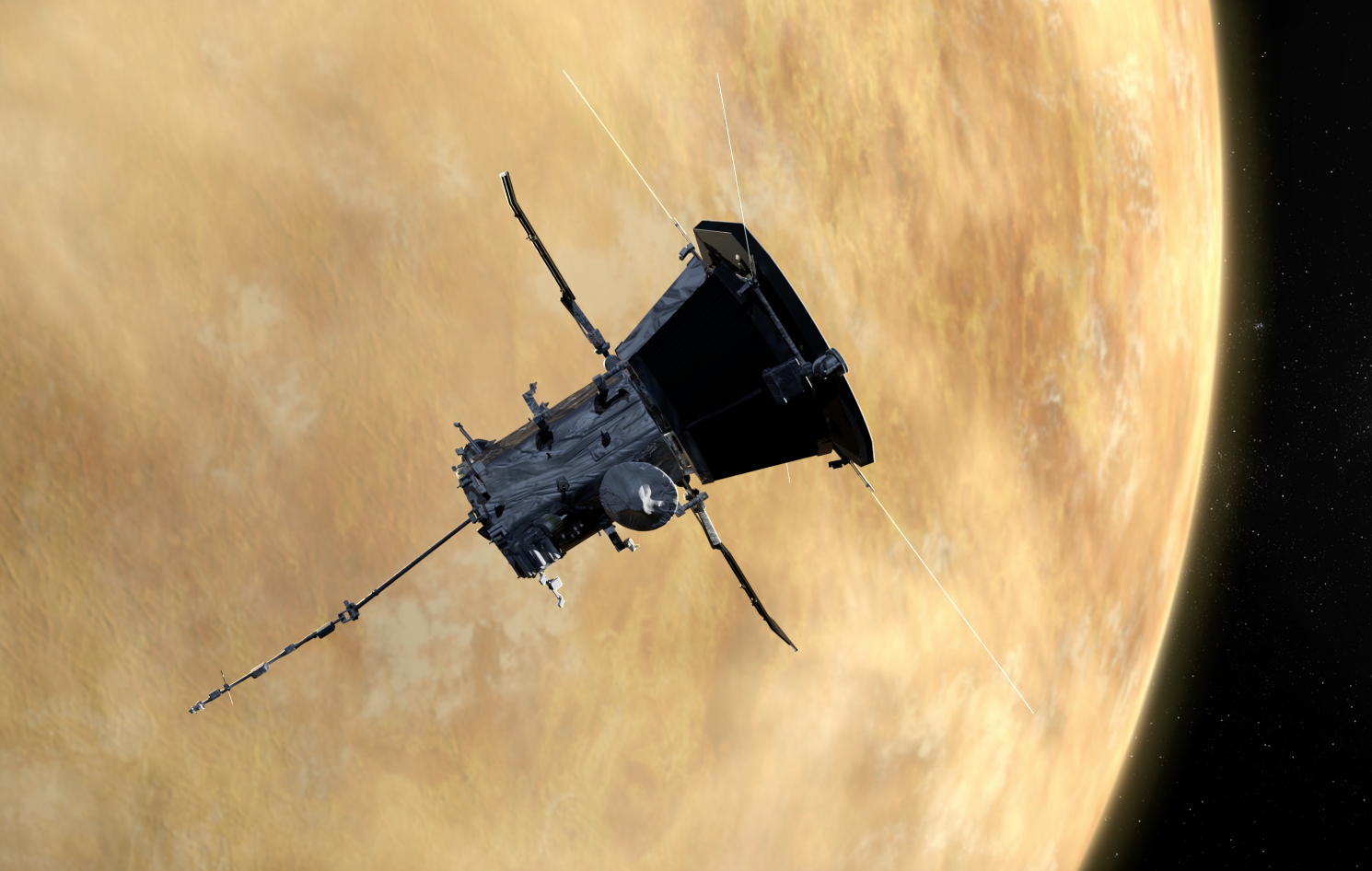

Hello, Venus! Parker Solar Probe Makes Second Planetary Flyby.

The sun is right there in the name of NASA's Parker Solar Probe, but a second mission of opportunity may make the spacecraft just as vital to Venus scientists as to those studying our local star.

Parker Solar Probe launched in August 2018, destined to spend seven years looping ever closer to the sun in hopes of sorting out some of the hottest mysteries about our star. But to do so, the spacecraft needed a carefully choreographed trajectory, one that included seven flybys of Earth's evil twin, Venus. And Venus scientists, who haven't had a dedicated NASA spacecraft since the mid-1990s, were not about to let that opportunity fly past them.

"The Venus flybys are like, if you have like a 48-hour layover in Paris, not leaving the airport," Shannon Curry, a planetary physicist at the University of California, Berkeley, told Space.com. "It would be crazy not to turn on [the instruments]." Curry and her colleagues made her case, and the Parker Solar Probe will gather its second batch of Venus data today (Dec. 26), as the probe makes its closest approach to the planet at 1:14 p.m. EST (1814 GMT).

Related: The Strange Case of Missing Lightning at Venus

Of course, Parker Solar Probe's instruments are designed to study a star, not a planet. They focus mostly on plasma, the hot mess of charged particles that makes up the sun. Traditionally, planetary scientists want very different instruments on their spacecraft: radar devices to map the surface, spectrometers to identify chemicals and the like. But that doesn't make plasma data superfluous.

Two dedicated Venus missions have carried plasma detectors to the world: NASA's Pioneer Venus Orbiter and the European Space Agency's Venus Express. But those spacecraft were built decades ago. "The stuff that they were able to put on [Parker] Solar Probe takes measurements faster, better, stronger, like the whole deal," Curry said.

And she and her colleagues have plenty of questions about Venus that plasma data could help answer. For today's flyby, the team is particularly interested in a feature called the bow shock, where the planet's neighborhood meets the solar wind of charged particles that constantly stream off the sun.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The precise location of the bow shock varies based on how active the sun is, which changes over the course of the 11-year solar cycle. "We're not positive it'll cross the shock or not, but that's actually important because it'll tell us physically where the shock is at this point in the solar cycle," Curry said. "It tells us a lot about what the sun's doing, and the shock is a nice gauge of that."

And the environment on either side of the bow shock differs dramatically. Outside the shock is the pristine solar wind and the effects of solar storms. But if Parker Solar Probe crosses inside the shock, scientists should be able to better understand how quickly Venus is losing its atmosphere.

"The magnetic fields pile up and actually sort of drag the atmosphere off. It's almost like a slingshot," Curry said. "That's one of the biggest ways the atmosphere of Venus gets removed, the sun's magnetic field lines."

Venus scientists are interested in a more detailed measurement of atmosphere loss, because atmospheric pressure affects what state water takes; it's Earth's even 1 bar of pressure that helps keep our oceans liquid. "At some point, maybe liquids could exist again [on Venus], or maybe they did before and we just don't know," Curry said.

But the Venus atmospheric-loss measurements will really crank up during Parker Solar Probe's next two flybys, in July 2020 and February 2021. These two visits will carry the spacecraft right through what scientists call the tail of Venus, which is where the atmosphere slips away from the planet.

"Those are going to be the super-important ones. I think these first two are almost — not like dress rehearsals, but it's really important to make sure we get everything right," Curry said. "Flybys 3 and 4 will tell us mountains about atmospheric escape at Venus and then a lot of other dynamics we just don't understand."

Curry said that Parker Solar Probe may be able to solve a long-standing mystery about the surface of Venus: whether the planet sports small, patchy crustal magnetic fields. So far, Mars is the only planet where scientists have seen this phenomenon. "It's like a little magnetic rash on its belly, like little bubbles with magnetic fields," Curry said. But no one's gotten a close enough look at Venus to check for them. "We might not [see them], and they might not even be there. We just don't know."

The results of the first Venus flyby, which took place in October 2018, prove the importance of practice. During the pass, the spacecraft ended up shutting its instruments down, convinced that they were pointing straight at the sun, which they aren't meant to do.

"We're just looking at Venus, not the sun. Venus is just a superbright planet the way it reflects," Curry said. "That's why the instruments got confused." Now, Curry said, the project team believes it's figured out how to keep that error from happening again.

And the Venus work is benefiting from a science bonus discovered by the main Parker Solar Probe team, which realized that the spacecraft could gather and send back more data than originally anticipated. Curry had been willing to fight for even just an hour of data on a flyby; during the first maneuver, the team got about 10 hours of observations.

Curry is hoping to build similar Venus collaborations with the European and Japanese team running the BepiColombo mission en route to Mercury and with Europe's Solar Orbiter mission. Like Parker Solar Probe, both of these spacecraft also need to make Venus flybys to reach their targets.

"These are the only measurements of Venus we're going to have for, frankly, it might be the next decade," Curry said. "We have nothing planned to go to Venus." And the missions NASA is considering don't carry plasma instruments like Parker Solar Probe does, so questions like atmospheric loss might go unanswered even then.

Combine those two factors, and the mission's accidental planetary science looks even more precious. "With Venus science," Curry said, "anybody who gets data is a hero."

- Should We Land on Venus Again? Scientists Are Trying to Decide

- Life on Venus? Why It's Not an Absurd Thought

- Can Venus Teach Us to Take Climate Change Seriously?

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.