'Observation' video game shows how an AI solves problems in space

Summer is here and may come some free time explore space in game form and one that caught our eye recently explores how a fictional artificial intelligence (AI) solves problems in space. So, naturally, we couldn't wait to launch right into it.

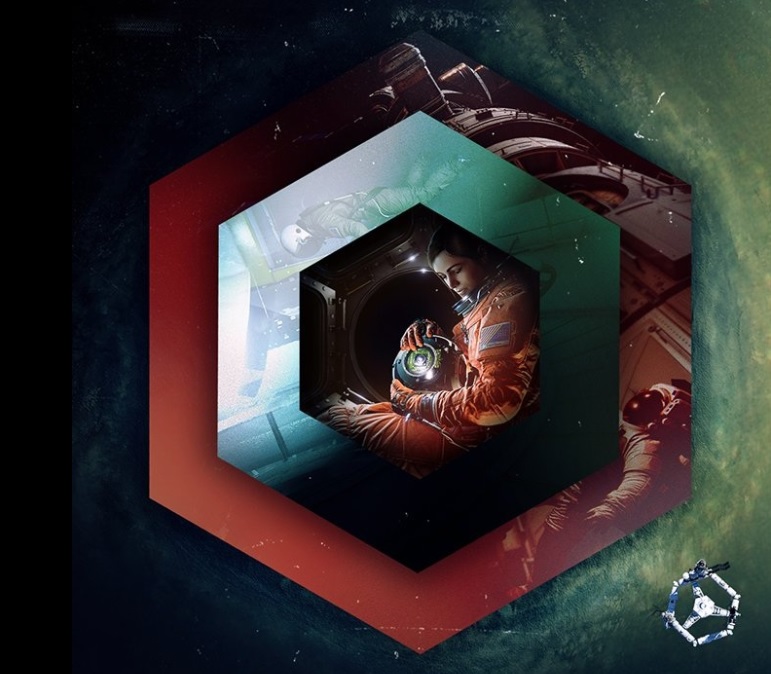

The game, "Observation," developed by No Code and published by Devolver Digital, was released for a few platforms in 2019 and expanded to Microsoft Xbox last year. Unusually for space games, you play as the AI and attempt to help an astronaut who is facing a catastrophic problem on a near-future space station.

Your mission as the AI, named SAM, is to open doors, turn valves and solve problems with an astronaut named Emma. An early tense moment in the game has you and Emma working together to contain a fire in the space station, and then Emma asks you to check out the source of the fire using your cameras and sensors.

Related: The latest space games news

Observation for PC on Steam: $27.29 now $9.79 on CDKeys

Help astronaut Emma solve problems, survive and find out what happened to her crew as he AI Sam in Observation from No Code and Devolver Digital.

In playing a few hours of the game, you can see why space is such a tough environment for astronauts and computers alike. You're always trying to fix things, and the SAM-Emma dynamic simulates how crews work together to fix real-time problems on the International Space Station (ISS). What we especially enjoyed was the idea that you sometimes have to try a few strategies to find the right solution, which is similar to what astronauts do during dynamic situations such as spacewalking.

To solve problems in the game, you have to not only search the environment but also mash buttons in a particular order, similar to the sequences gamers used in the 2018 video game "Detroit: Become Human" that explored the rights of androids. Luckily, though, "Observation" is more forgiving than "Detroit," and the astronaut will often take over if you're having trouble finding the solution.

The game is a good fit if you enjoy problem solving and linking as you go, but if you're looking for quick action and solutions, you won't enjoy the experience. Some of the thought puzzles require you to sit for a while and think logically, playing through different camera angles and asking your crewmember for help. But be patient, and rewards will come.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Space.com spoke with Jon McKellan, creative director for No Code, to learn more about the development process behind the game. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Space.com: What was the inspiration behind "Observation"?

Jon McKellan: The idea came from an article I had read years ago, [which described a thought experiment] taking an antagonist from a movie and recontextualizing the movie with them as a protagonist. The example it cited was the alien from the original "Alien" (1979) movie. I had just finished five years of working on survival horror game "Alien: Isolation" (2014), and I was heavily immersed in "Alien." Seeing the film from the alien's perspective was eye-opening. It's about a creature that is born in a hostile environment with a crew trying to kill it, and all it wants to do is eat!

So I started to think about other favorite films and stories that could go through a similar process. I immediately jumped to "2001: A Space Odyssey" (1968) and thought about what the computer HAL might be going through — what it might feel like to suddenly have a consciousness, or to have a sudden existential awakening — and that became the seeds of the game.

Space.com: How similar or different is this game from other ones you or your company have made in the past?

McKellan: We had pitched — and were in the process of signing — "Observation" when we made an experimental adventure game, "Stories Untold" (2017). Signing took a while! We actually road-tested some gameplay concepts for "Observation" in "Stories Untold." Our primary objective has always been telling great interactive stories, where player agency is in lockstep with the character's development. The gameplay we ask the player to take part in is both appropriate to the moment and characters, and believable in terms of its presentation.

In the case of "Observation," it's also about science. There's no putting-gems-in-a-statue's-eye-to-unveil-a-secret-pathway type puzzle. Instead, the game is about trying to stabilize an experimental and miniaturized fusion reactor, or to deal with airlock compression between modules. It's all as grounded and believable as possible, while still being exciting and unusual for the audience.

Space.com: What sci-fi franchises and real-life experiences did you draw from to build the game?

McKellan: The majority of situational "problems" the player faces in the game come from us theorizing about what could go wrong on the International Space Station and how you might solve it. We spent months poring through reference material and books about the station, and the various systems in place to deal with the multitude of problems that might arise.

Aside from that, a library of movies from the last five decades helped inform the atmosphere and tone. For the issues that directly affect Emma the crewmember, we drew from "Gravity" (2013), which very intimately shows how the physical dangers of being in space might affect a person. For the player character SAM, it was more things like "Alien" (1979), "Event Horizon" (1997) and, of course, "2001: A Space Odyssey" (1968). A big part of the game is that you view 90% of the action via the onboard CCTV system, so we're often having to tell the story at quite a distance. "Found footage" movies such as "Blair Witch" (2016) or "Europa Report" (2013) were really useful in learning how to do that, and to take advantage of the viewpoint.

Space.com: What experts, if any, did you talk to in the space world to build the game, and what did you learn from them?

McKellan: We didn't get much opportunity to speak to many experts, sadly. Trying to make contact as a game studio seems to be a lot harder than when you are making a film. Hopefully, that will change as time goes on, and more clear and standardized routes for communication between our industries are put in place. Thankfully, though, the European Space Agency and NASA put so much great material out there to the public that we had much to reference in building our world and our story.

We obviously have a bit more of a supernatural or alien scenario, so we figured out what that would change and went from there. For example, if the ISS was suddenly at another planet in the outer solar system, its solar panels would be far less effective. We weave that kind of science — and how you might deal with it — into the story and gameplay

Space.com: What made you choose to tell the story from the point of view of the computer?

McKellan: What made it fascinating to me was the idea of an artificial intelligence becoming "awake" right at the moment where the player takes control. The player is the new consciousness. They provide the uncertainty, the human approach to problem solving, the empathy for other characters and, of course, the flaws and mistakes and subjectivity that comes with the territory. It meant that the character of SAM can develop in perfect synchronization with the player experience. SAM and the player have an identical viewpoint in the world, and — with only one exception you'll see while game playing — never does SAM say or do something the player isn't expecting.

On top of that, there is a layer of player action that has a direct impact on the story. For example, as a player, it makes sense to switch to a camera in a room and listen to a conversation, or open doors and explore. But to the crew in-game, that is an extremely creepy thing to do! It meant that the innocent actions of SAM had this other meaning to the crew, really making the player think about their role in the story. This was the main drive for the whole experience. The player is almost roleplaying the game without realizing it.

Space.com: What do you hope players will get out of the game?

McKellan: We went to huge lengths to create depth in the story, the background details, the mysterious languages and so on. I would say the best mindset is always thinking, "What would an AI do?" Some of the puzzles are straightforward, but others require shifting your perspective a bit. When we see a fire and are asked to put it out in a game, we tend to think about how we would do that physically, maybe as a crewmate or something.

But here, you play a different supporting role. You're thinking about the steps to achieve it the way an AI would: connect to a system, enable it, notify the crew of the problem in the first place, that kind of thing. It's — to us, the humans — a really fascinating way of experiencing and taking part in an interactive story. It makes for some exciting moments from an all-new angle that only a game could do.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.