Newly Spotted Asteroid with Supershort Year Swings Closer to the Sun Than Mercury

It's as if the year ended on May 31.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

By watching the skies at the brink of sunrise and shortly after nightfall, astronomers spotted a hunk of rock with the shortest-known asteroid "year" to date.

The Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) camera scans the skies quickly every night from the Palomar Observatory, located 90 miles (145 kilometers) southeast of Los Angeles. ZTF looks for anything that's changing over time: not only stars that flash or explode but also asteroids that pass by, like the one described in a Monday (July 8) statement from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

The newly discovered asteroid — now called 2019 LF6 — orbits the sun every 151 days, or about the time between Jan. 1 and the last day of May.

Related: Boulders on Diamond-Shaped Asteroids Hint at Dusty Landslides

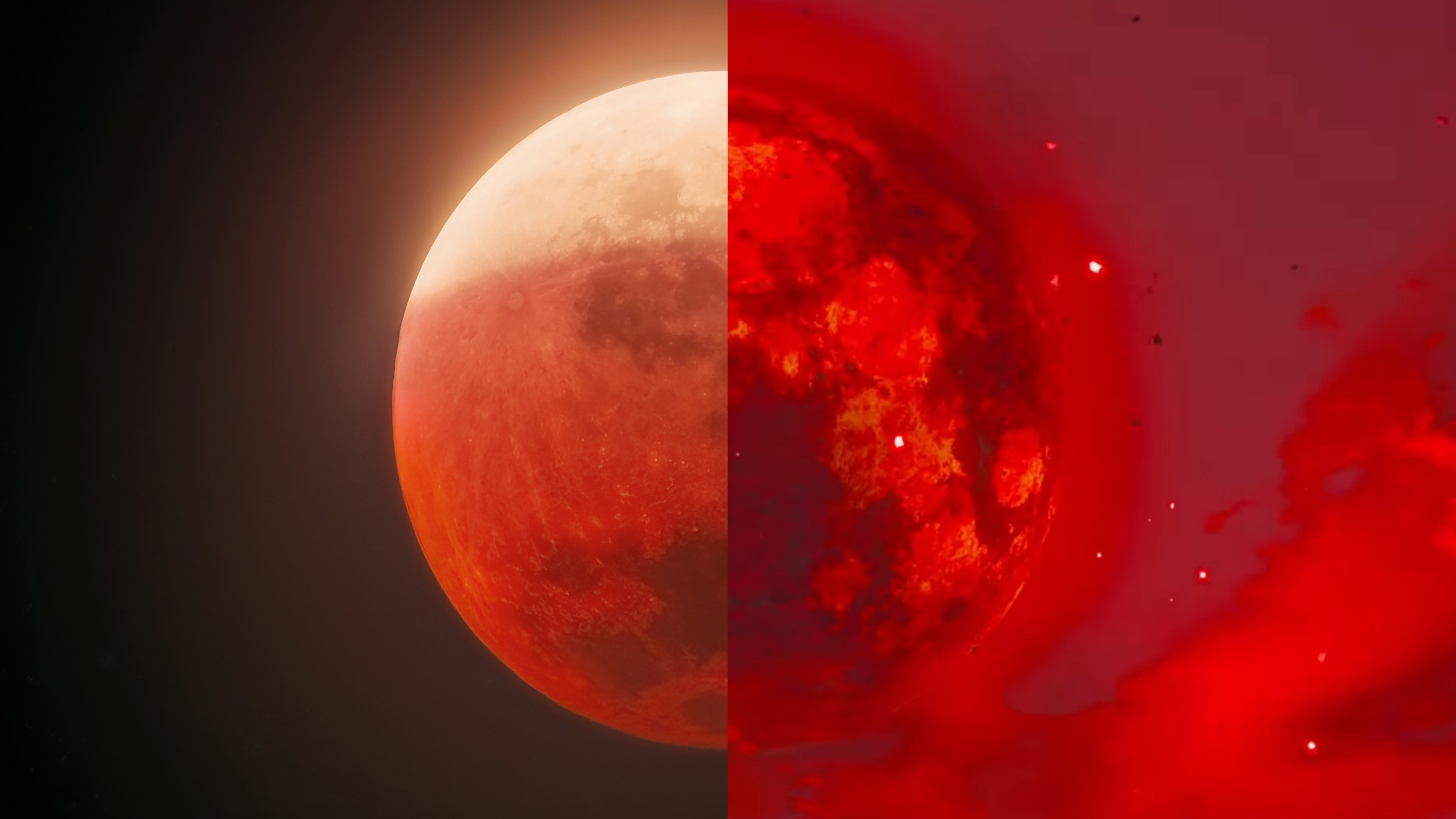

This asteroid is one of 20 known so-called Atira asteroids, a class of near-Earth objects orbiting the sun closer than Earth. The orbit of this 0.6 mile-long (1 km-long) hunk of rock swings from beyond Venus to even closer to the sun than Mercury.

"LF6 is very unusual both in orbit and in size — its unique orbit explains why such a large asteroid eluded several decades of careful searches," Quanzhi Ye, the postdoctoral scholar at Caltech who discovered 2019 LF6, said in a statement.

According to Ye, these asteroids, huddled near the sun, are best seen 20 to 30 minutes before sunrise or after sunset. Ye developed a dedicated observing campaign called Twilight to find Atira objects, and along with Wing-Huen Ip from the National Central University of Taiwan, Ye has now discovered two Atira objects. Before the recent finding, the first Atira asteroid spotted by Twilight, called 2019 AQ3, had the shortest known year of any asteroid, at 165 days.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

These objects are also fascinating because of their tilted orbits. "Both of the large Atira asteroids that were found by ZTF orbit well outside the plane of the solar system," Caltech professor Tom Prince said in the same statement. "This suggests that sometime in the past they were flung out of the plane of the solar system because they came too close to Venus or Mercury."

In addition to these two Atira objects, ZTF has found about 100 near-Earth asteroids and 2,000 main-belt space rocks orbiting between Mars and Jupiter, according to Caltech officials. Ye hopes his skywatching campaign will lead to more Atira discoveries and that NASA pursues future near-Earth object projects like the proposed NEOCam mission, which is designed to look for asteroids closer to the sun.

- NASA Will Aim a DART at Target Asteroid in Upcoming Deflection Test

- Dawn Mission: Shedding Light on Asteroids

- Water Found in Tiny Dust Particles from Asteroid Itokawa

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.