About 17,000 Big Near-Earth Asteroids Remain Undetected: How NASA Could Spot Them

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Humanity needs to step up its asteroid-hunting game.

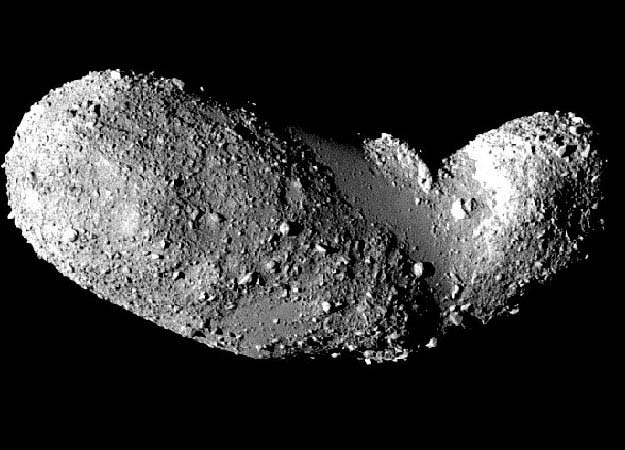

To date, astronomers have spotted more than 8,000 near-Earth asteroids that are at least 460 feet (140 meters) wide — big enough to wipe out an entire state if they were to line up our planet in their crosshairs. That sounds like good progress, until you consider that it's only about one-third of the 25,000 such space rocks that are thought to zoom around in Earth's neighborhood.

"There's still two-thirds of this population out there to be found," Lindley Johnson, planetary defense officer at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C., said during a presentation last week with the agency's Future In-Space Operations working group. "So, we have a ways to go." [In Pictures: Potentially Dangerous Asteroids]

A near-Earth object (NEO) is anything that comes within about 30 million miles (50 million kilometers) of our planet's orbit. The overall NEO population is almost incomprehensibly large; there are likely tens of millions of such space rocks between 33 feet and 65 feet (10 to 20 meters) in diameter, Johnson said.

Asteroids of this relatively small size can cause damage on a local scale. For example, the object that exploded over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk in February 2013, smashing thousands of windows and wounding more than 1,200 people, measured about 62 feet (19 m) across, scientists have said.

But the really worrisome asteroids are the big ones. So, in the 1990s, Congress directed NASA to find 90 percent of the NEOs that are at least 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) in diameter — a mandate the space agency fulfilled in 2010. Currently, 887 of these mountain-size space rocks are known, and perhaps just 50 or so are left to be discovered, Johnson said. (None of the cataloged behemoths pose a threat to Earth for the foreseeable future.)

In 2005, NASA got some further instructions from lawmakers: Spot 90 percent of all NEOs 460 feet and larger by the end of 2020. It's clear at this point that the agency will not meet that ambitious deadline. And getting such a detailed handle on the NEO population will require the launch of a dedicated asteroid-hunting space mission, according to a& NASA-commissioned study that was published in September 2017.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

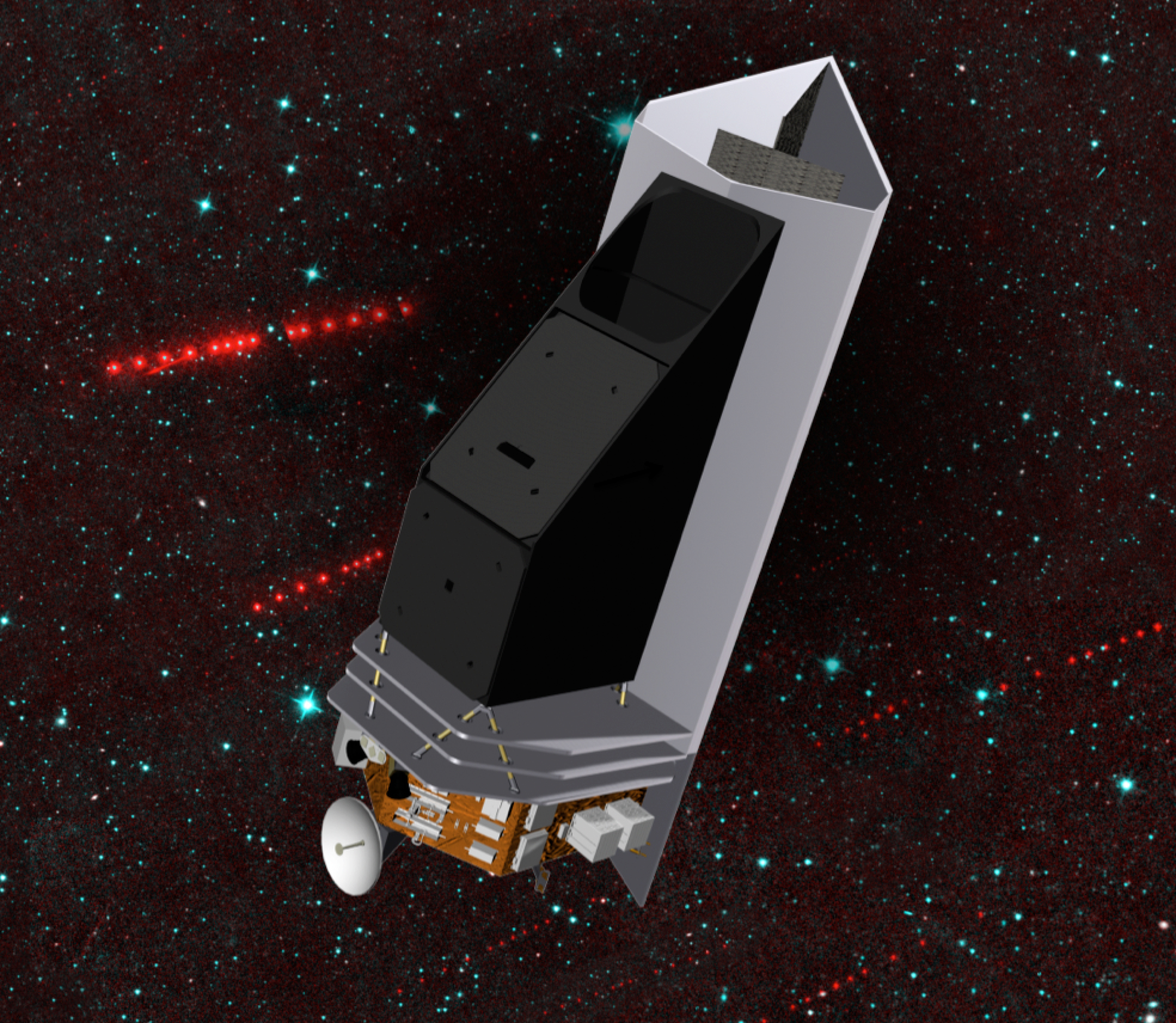

The space telescope for such a mission would ideally set up shop at the sun-Earth Lagrange point 1, a gravitationally stable spot about 930,000 miles (1.5 million km) from our planet, and scan the heavens in infrared light using a telescope at least 1.6 feet (0.5 m) wide, the study found. Such a mission's observations, combined with the contributions of ground-based telescopes, could probably bag the required number of 460-footers in a decade, Johnson said.

NASA is already working on such a space project — a concept mission called the Near-Earth Object Camera (NEOCam). NEOCam was one of five finalists for the next launch opportunity in NASA's Discovery Program, which funds relatively low-cost and highly focused missions. NEOCam ended up missing out on that slot — NASA picked two other asteroid-studying missions, called Lucy and Psyche — but it did get another year's worth of funding.

There's still hope that NEOCam will fly someday, Johnson said.

"We have taken it over into the Planetary Defense Program," he said. "All we are [lacking is] the entire budget to be able to put a mission like this — a space-based survey capability, which is highly recommended and very necessary for our future capabilities — into development." [Photos: Asteroids in Deep Space]

A viable planetary-defense plan requires more than just asteroid detection, of course; humanity also needs to be able to deflect any dangerous space rocks that are headed our way.

NASA and its partners around the world are working on potential solutions to this problem as well. For example, NASA aims to launch a mission called the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) in 2020. If all goes according to plan, in October 2022, DART will slam into the 500-foot-wide (150 m) moon of the asteroid (65803) Didymos, which itself measures about 2,600 feet (800 m) across. This impact will change the orbit of "Didymoon" in ways that Earth-based telescopes should be able to detect, NASA officials have said.

DART will be a demonstration of the "kinetic impactor" deflection strategy. NASA had also planned to test the "gravity tractor" technique — using a fly-along probe to gradually nudge an asteroid off course via gravitational forces — in the coming years as a part of the agency's Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM). But the White House zeroed out funding for ARM in last year's federal budget request, and that mission is no more.

There's one more possible way to knock out an incoming asteroid, and it was made famous by the 1998 movie "Armageddon." Blasting a space rock apart with a nukewouldn't be the first choice of most scientists or policymakers, but such an extreme measure may be the only way to deal with a big space rock detected with little lead time. (And this would be a robotic mission, by the way; you wouldn't need a space cowboy like Bruce Willis to get the job done.)

Such preparatory work shouldn't unduly alarm the public, Johnson stressed; the odds that a big asteroid will strike Earth are very low on a day-to-day basis.

"These are very rare events," he said. "But they're also an event that, if we don't find this population, can happen any day on us."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.