NASA fires up its 1st SLS megarocket for moon flights in a critical engine test

The Artemis 1 core booster could launch to the moon this year.

STENNIS SPACE CENTER, Miss. — The second time was a charm for NASA's massive new moon rocket.

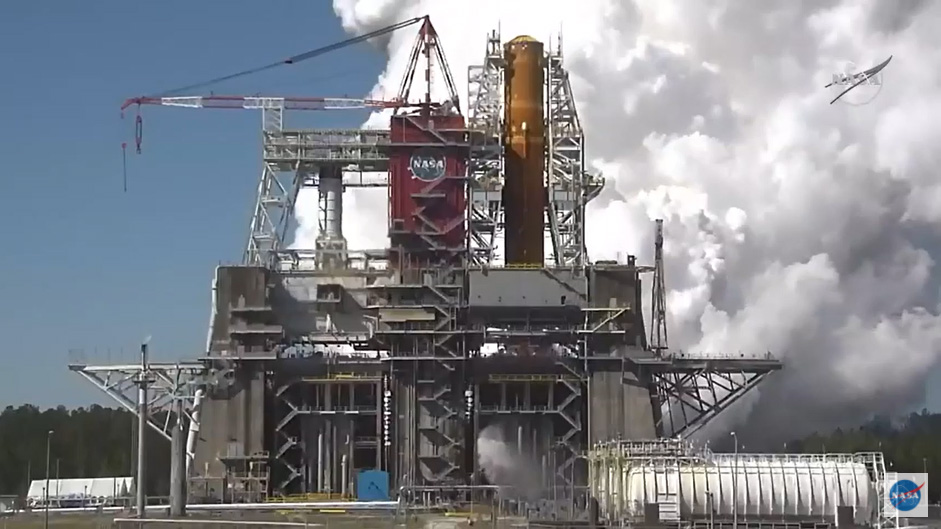

The core stage of the Space Launch System (SLS), the rocket that NASA is developing to take astronauts to the moon, Mars and other distant destinations, fired up for a critical preflight test on Thursday (March 18).

Smoke and flames billowed from the four RS-25 engines that power the SLS core booster as it roared to life while perched atop a test stand here at NASA's Stennis Space Center. Ignition occurred at 4:37 p.m. EDT (2037 GMT), when 700,000 gallons (2.6 million liters) of cryogenic fuel began flowing through the engines.

Video: Hot fire! NASA SLS megarocket's core stage tested for over 8 minutes

The "hot fire" test ran for just under 500 seconds, a duration that NASA had planned and hoped for. The trial was a repeat of an identical test that occurred on Jan. 16. But that earlier engine test ended much earlier than expected, with the engines shutting down just over one minute after roaring to life.

The briefness of the January burn was attributed to the hydraulic system associated with one of the engines; that system apparently exceeded conservatively preset limits in one parameter, triggering a shutdown, investigators determined. NASA evaluated data collected from the first test and decided to go ahead and redo the test to make sure the core stage was functioning as expected before being shipped to the launch site, NASA's Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida.

"What a great day, and a great test," NASA Acting Administrator Steve Jurczyk said during a post-test news conference Thursday evening.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This is a major milestone advancing our goals for Artemis," he added. "I'm almost speechless at how well things went today."

Artemis is NASA's program of crewed lunar exploration, which aims to send astronauts to the moon's surface as early as 2024 and establish a long-term, sustainable human presence on and around Earth's nearest neighbor by the end of the decade.

NASA's big new moon rocket

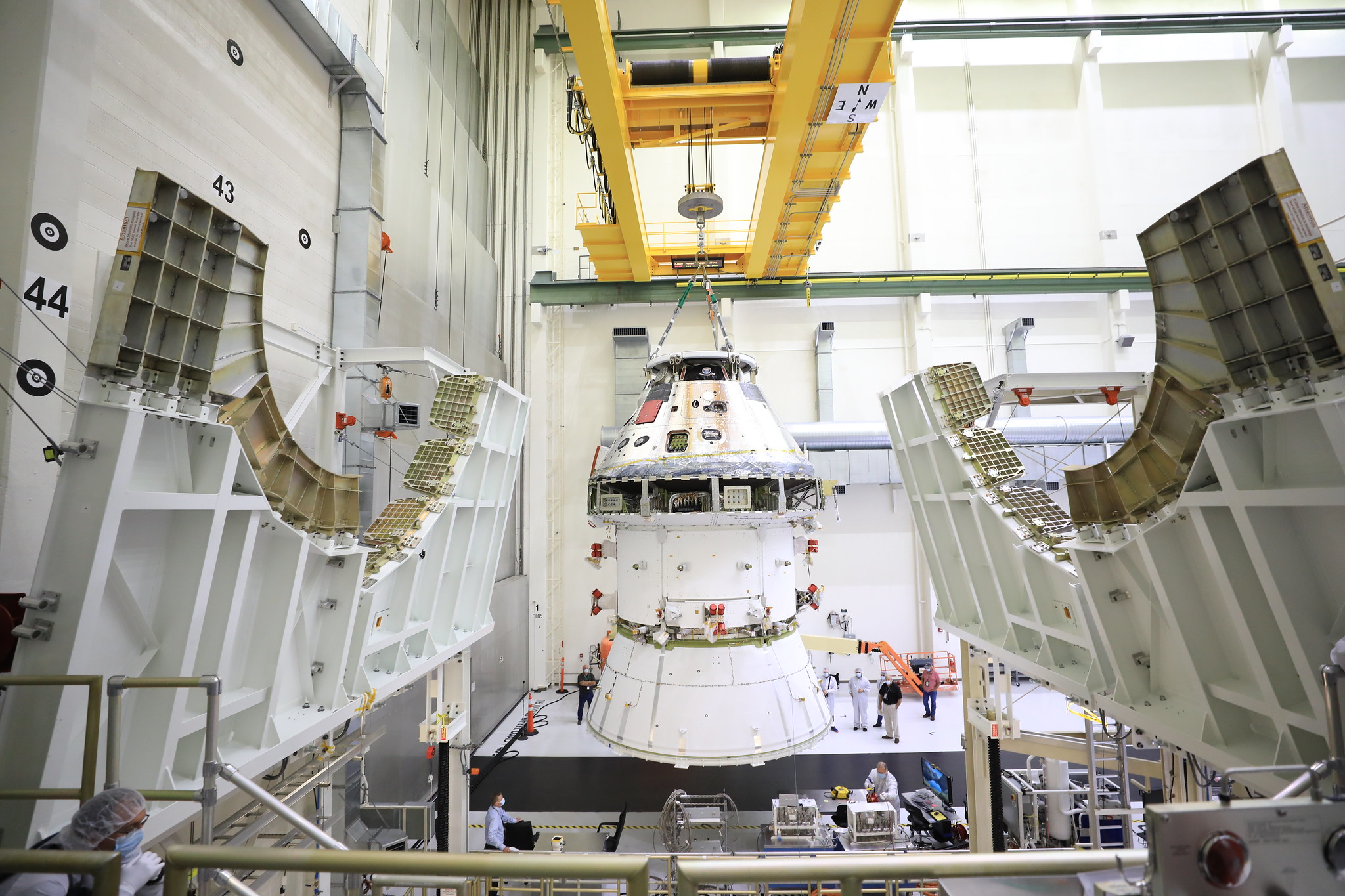

SLS is a crucial part of Artemis. The program's initial flight, Artemis 1, will use an SLS rocket to send NASA's Orion spacecraft on an uncrewed trip around the moon.

Artemis 1 is currently scheduled to launch by the end of the year, although it's unclear if that will actually happen. Following the first SLS core hot fire test, then-NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said it was too early to tell if the vehicle could still make its debut by the end of the year.

The agency is expected to make a decision on when SLS will get off the ground after this test.

Prior to the Jan. 16 hot fire, John Shannon, vice president and program manager for SLS at Boeing, the prime contractor for the rocket's core stage, said that the engines need to run for about 250 seconds to get the data needed to proceed with shipping the core stage to KSC. The initial test stopped well short of 250 seconds, and before the teams were able to gimbal (or move) the engines, which is a key testing maneuver. So the team decided a second test was needed.

Hot fire test, take two

All systems were "go" on Thursday as the teams progressed through the countdown that started early that morning. The vehicle was loaded with super-chilled liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen before its engines lit at approximately 4:37 p.m. EDT (2037 GMT).

The hot fire is a key test that puts the SLS core booster components — the four RS-25 main engines, fuel tanks and the rocket's computers and avionics — through their paces. The test simulated a launch while holding the rocket firmly in place, affixed to a test stand.

The same test stand at Stennis was used to test the engines on both NASA's Saturn V rocket and space shuttle orbiters. Both the SLS core stage and the test stand have instrumentation that recorded data during the test.

"The test stand is just as important as the vehicle is today," said Chandler Scheuermann, an SLS program manager at NASA's Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans.

NASA was hoping for the quartet of engines to fire longer than the 67 seconds they did during the first test, and that wish came true as the test ran for 499.6 seconds.

"Yeah, so they clearly got the full duration that they were after, which is really great news," said a commentator on NASA's live hot fire webcast. "I think you heard the applause."

"We needed four minutes, and we did twice as good as we needed," Julie Bassler, SLS stages manager at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama, said during Thursday evening's news conference. "So, big thanks to the team."

SLS coming together

First conceived in 2011, the SLS is finally coming together for an uncrewed trip around the moon sometime later this year.

Each SLS rocket employs four RS-25 engines to launch its 212-foot-tall (65 meters) core stage. It also relies on two solid rocket boosters strapped to the core's sides and an upper stage to propel NASA's Orion crew capsule beyond low Earth orbit.

The Orion spacecraft planned for that first SLS launch is now complete and is being processed for flight at KSC. The boosters are now fully stacked and positioned in the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) at KSC, waiting on the core stage.

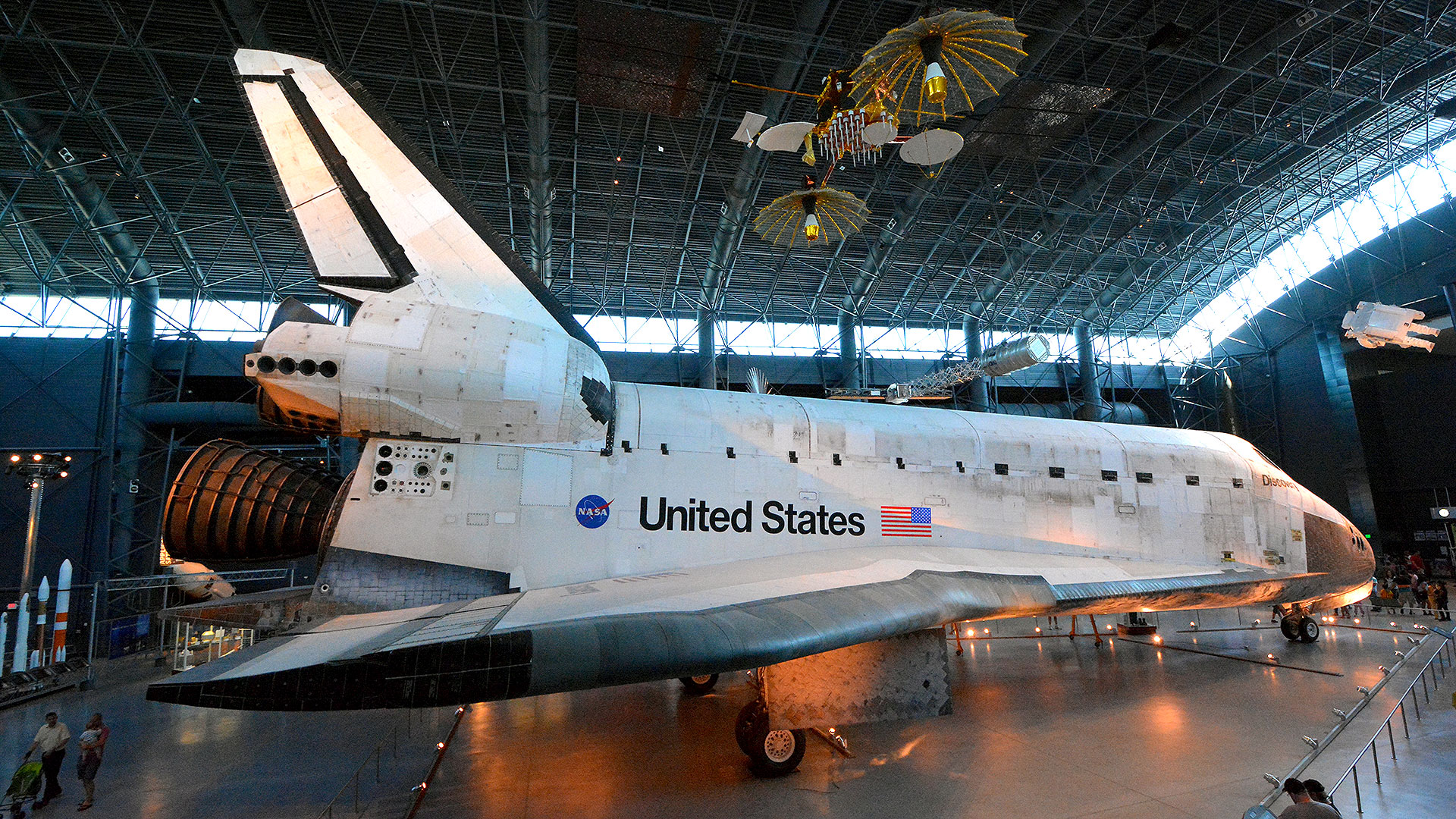

The agency salvaged 16 RS-25 engines that were originally used in the space shuttle program. The engines even flew on key missions, including one to service NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and one that helped launch the final shuttle flight in 2011.

The 16 engines in stock will be used on the first four SLS launches, for Artemis missions 1 through 4. (NASA contracted Aerojet Rocketdyne to build 24 more RS-25 engines for flights beyond that.)

Since the engines on the first few missions are shuttle leftovers, the agency had to add new computer controllers as well as other upgrades to ensure the engines can handle the higher performance demands of an SLS launch.

The solid rocket booster segments are also recycled from the shuttle program. After they were refurbished, each segment was stacked on top of one another and assembled in the VAB.

The stacked SLS-Orion combo will also feature a launch-abort system that's designed to pull the capsule away from the rocket if something goes wrong during a launch.

Space Launch System: NASA's rocket for Artemis moon missions explained

Road to the test pad

NASA has been systematically testing the various components of the SLS over the past few years.

The agency tested each of the main engines separately to ensure they fired up as expected. And to ensure the flight hardware meets design expectations, NASA began what it calls a "green run," a lengthy series of trials that tested the vehicle's avionics, countdown and launch timeline, fueling procedures and more.

The testing went smoothly but was complicated by a global pandemic as well as an unusual number of tropical storms and hurricanes impacting the test sites. This caused more delays for the launcher’s testing.

The firing of the four RS-25 engines on Thursday closed out the green run, which began with stress tests on the physical structure of the rocket.

The goal of the hot fire test was to run through launch day procedures and ignite the four engines, allowing them to burn for just over eight minutes — roughly the duration that they will burn during an actual flight.

As expected, the engines roared to life, producing 1.6 million pounds of thrust as they burned for 499.6 seconds. The full-duration test will provide engineers with massive amounts of data on how the core stage performed.

"That was epic," NASA astronaut Zena Cardman told Space.com following the test. "I can't wait to see the data they collected."

"It was an amazing test," said NASA astronaut Jessica Meir, who was also at Stennis for Thursday's test. "Congratulations to the whole NASA team."

It will take the teams several days to review the data before clearing the core stage for its next task: refurbishment and eventual transportation to KSC.

Terabytes of data were collected, and according to Bassler, if all goes as planned, the core stage could ship to Florida in mid-April.

Once it arrives, the booster will be integrated with the rest of the vehicle that is already onsite. This includes its two solid rocket boosters, which are currently being stacked in the VAB at KSC.

The solid rocket boosters were previously tested before being shipped in segments to Florida. Each booster consists of five segments that are stacked on top of one another. Those segments are complete and ready to be integrated with the core stage.

The Orion spacecraft is also complete and nearly ready to be affixed to the top of the SLS once the rocket is fully assembled.

This story was updated at 7:50 p.m. EDT on March 18 with details and quotes from the post-test news conference.

Follow Amy Thompson on Twitter @astrogingersnap. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Amy Thompson is a Florida-based space and science journalist, who joined Space.com as a contributing writer in 2015. She's passionate about all things space and is a huge science and science-fiction geek. Star Wars is her favorite fandom, with that sassy little droid, R2D2 being her favorite. She studied science at the University of Florida, earning a degree in microbiology. Her work has also been published in Newsweek, VICE, Smithsonian, and many more. Now she chases rockets, writing about launches, commercial space, space station science, and everything in between.