NASA's Moon-by-2024 Push Could Help Put Astronauts on Mars by 2033, Chief Says

"The moon is the proving ground," Bridenstine said.

The Trump administration's decision to ask NASA to land astronauts on the moon in 2024 was driven by its ambitious goal of sending astronauts to Mars in the 2030s, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine told lawmakers in a hearing of the House Science, Space and Technology Committee on Tuesday (April 2).

NASA was already planning to land astronauts on the moon in 2028 with the ultimate goal of going to Mars in the 2030s — until just last week, when Vice President Mike Pence announced new plans to have "boots on the moon" in 2024. Doing so could put NASA on track to land astronauts on Mars in 2033, Bridenstine said at the hearing. However, committee members expressed some doubt over the feasibility and necessity of that accelerated timeline.

"We want to achieve a Mars landing in 2033," Bridenstine said. "In order to do that, we have to accelerate other parts of the program, and the moon is a big piece of that."

Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson, D-Texas, the chairwoman of the committee, questioned Bridenstine about the need for undertaking a "crash program" to rush to the moon in just five years, while criticizing Pence's claim that the U.S. is in a new space race.

"The simple truth is, we are not in a space race to get to the moon. We won that race a half-century ago," she said.

Related: Can NASA Really Put Astronauts on the Moon in 2024?

In 2016, former President Barack Obama directed NASA to shoot for a human mission to Mars sometime in the 2030s. After President Donald Trump took office the following year, Trump entertained the idea of getting there by 2024 — a goal that much of the space industry deemed unrealistic — and signed a bill directing NASA "to study the feasibility of the launch of a human spaceflight mission to Mars in 2033." But some members of Congress are still not convinced that NASA has the resources to meet Trump's expectations.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

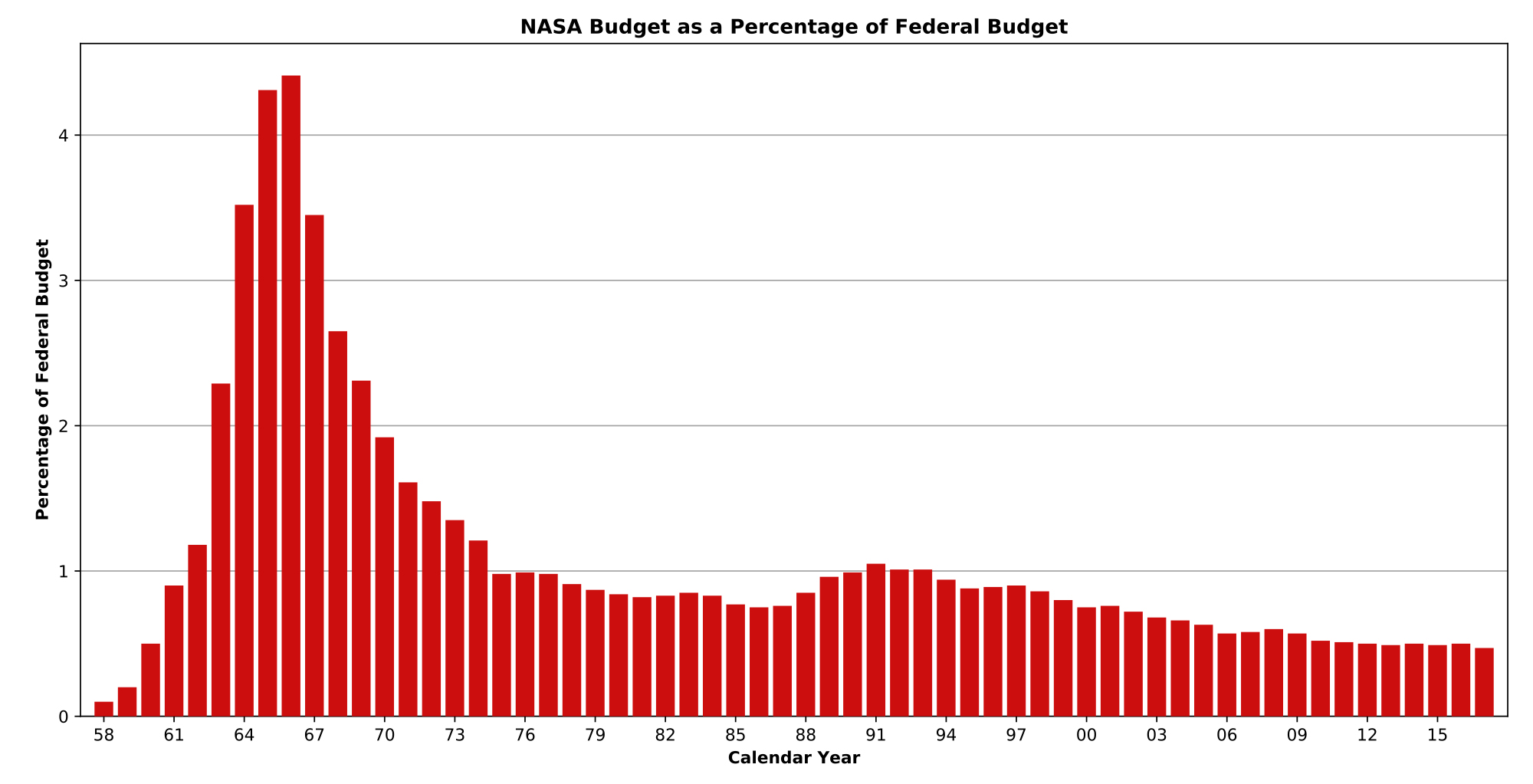

"I'm sure you've seen the charts that show the percentage of our federal budget, or a percentage of GDP, that the NASA budget was back when we were going to the moon, and now we're going to go again — and to Mars," representative Don Beyer, D-Va., said to Bridenstine during the hearing. "Realistically, how do you expect to be able to do this when our NASA budget is a fraction of what it was before?"

"We're making assessments right now as to if we're going to land in 2024 — which we're going to do," Bridenstine said. "The question is, how do we achieve that?" To start, NASA is preparing to file a budget amendment, because the agency's fiscal year 2020 budget request was filed before the Trump administration announced its plans to land humans on the moon in 2024. Ideally, that revamped budget request should provide NASA with the funds it needs to start working toward that goal. However, it seems highly unlikely that NASA's funding will ever reach the same levels that it did during the Apollo era.

The federal budget request released by the White House Office of Management and Budget on March 11 gives NASA a total of $21 billion and allocates about $5 billion to research and development of deep-space exploration systems, including the new Space Launch System (SLS) megarocket, the Orion crew capsule and the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway, a proposed lunar space station.

In addition, the budget request includes about $1 billion for "new lunar surface technologies required for humans to successfully operate on the lunar surface." This includes money for the development of new spacesuits, a power supply on the lunar surface and in situ resource utilization, or the ability to use natural resources found on the moon.

For contrast, NASA's overall budget at the height of the Apollo program in 1966 was $5.9 billion, which is about $46 billion today when adjusted for inflation. NASA estimated that the entire Apollo program, which lasted from 1960 to 1972 and successfully executed six lunar landings, cost a total of $220 billion, with inflation. That averages to about $37 billion per landing.

Bridenstine argued that Apollo-era funding levels won't be necessary to return to the moon in 2024, because "we have more capabilities right now," such as the miniaturization of electronics, reusable launch vehicles and commercial launch vehicles, he said during the hearing. "We have a lot of hardware that exists right now that didn't exist in 1961 and in 1962 when President Kennedy made his famous speeches."

The NASA administrator did not offer an estimate of exactly how much it will cost to return to the moon in 2024, but said the agency is working with the White House on a budget amendment that should make that cost more clear. That amendment will be ready on April 15, Bridenstine said.

"We have an opportunity here, should we choose to accept it, to no-kidding get to the moon in 2024," Bridenstine said. "That kind of vision is in front of us if we want to go after it, and I think we can achieve it, given what is available right now." Bridenstine acknowledged that NASA would need additional resources to reach that goal, adding that bipartisan consensus will be key to securing the necessary funds.

While planting American boots on the moon is NASA's current priority, the moon is not the end goal. Rather, it will help NASA develop the technology needed to send astronauts to Mars.

"The moon is the proving ground," Bridenstine said. "We have to be able to utilize the resources of another world, and on the moon we now know that there's hundreds of millions of tons of water ice," which can be used to make breathable air, drinkable water and even fuel for spaceships. "Liquid oxygen, liquid hydrogen is the same fuel that powered the space shuttle, and it's the same fuel that will power the SLS rocket, so we need to utilize those resources," Bridenstine said.

"When we go to Mars, we're going to be there for at least two years," Bridenstine said. "So, we need to learn how to live and work in another world. The moon is the best place to prove those capabilities and technologies. The sooner we can achieve that objective, the sooner we can move on to Mars, and that's ultimately the objective here."

- NASA Chief Says 'Nothing Off the Table' as Agency Develops New Moon Plan

- Going Back to the Moon Won't Break the Bank, NASA Chief Says

- Manned Mars Plan: Phobos by 2033, Martian Surface by 2039?

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Hanneke Weitering is a multimedia journalist in the Pacific Northwest reporting on the future of aviation at FutureFlight.aero and Aviation International News and was previously the Editor for Spaceflight and Astronomy news here at Space.com. As an editor with over 10 years of experience in science journalism she has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy. She currently lives in Seattle, home of the Space Needle, with her cat and two snakes. In her spare time, Hanneke enjoys exploring the Rocky Mountains, basking in nature and looking for dark skies to gaze at the cosmos.