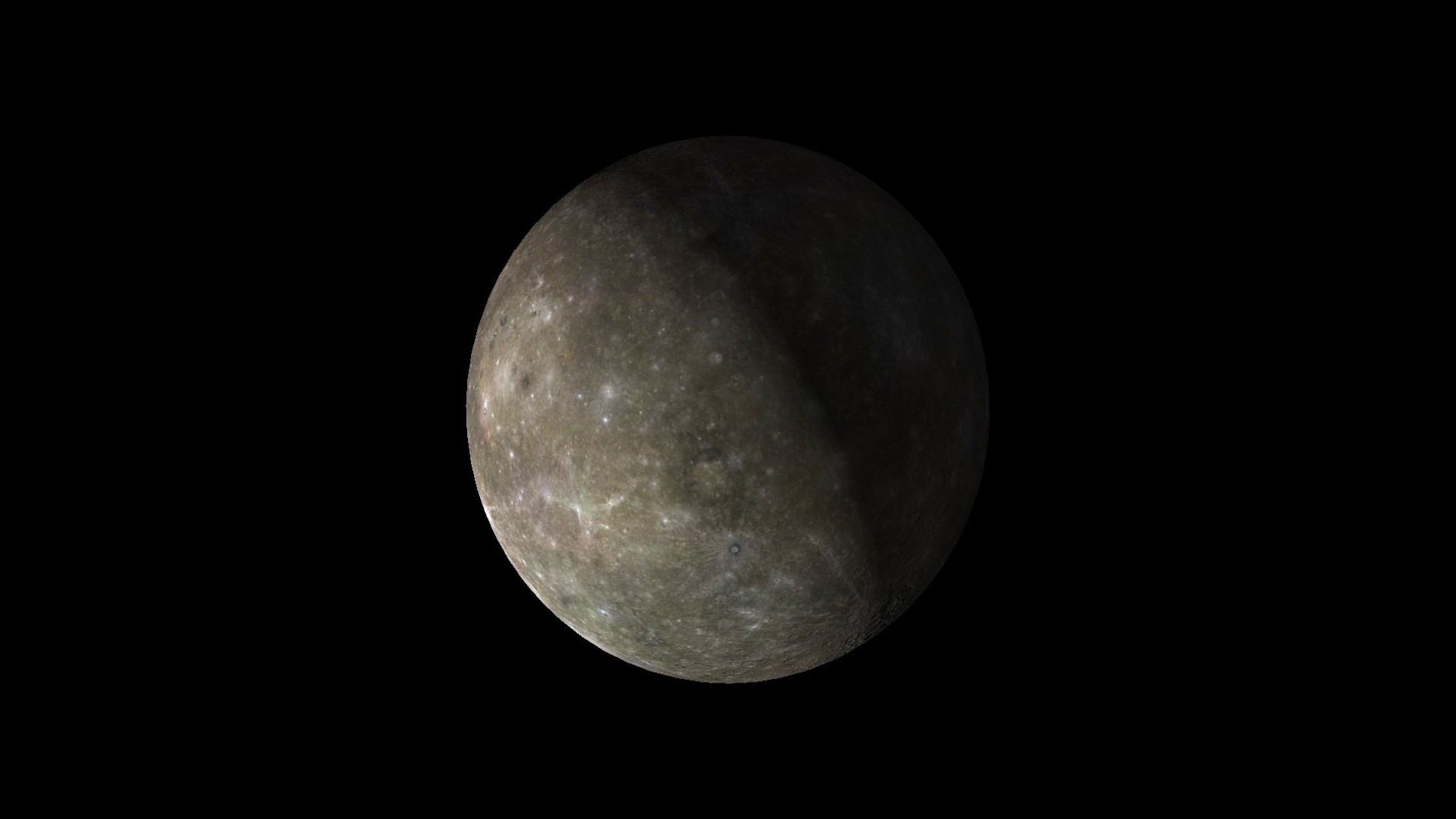

The crescent moon meets up with Mercury tomorrow morning (Feb. 18)

The sliver of the moon still visible will be in conjunction with the closest planet to the sun this weekend.

The crescent moon meets up with the solar system's fastest planet, Mercury, in the sky on Saturday (Feb. 18). The closest planet to the sun and the smallest planet in the solar system, named after the Roman god of speed and messenger to the Gods, Mercury, will share the same right ascension with the 28-day-old moon in the sky, an arrangement called a "conjunction."

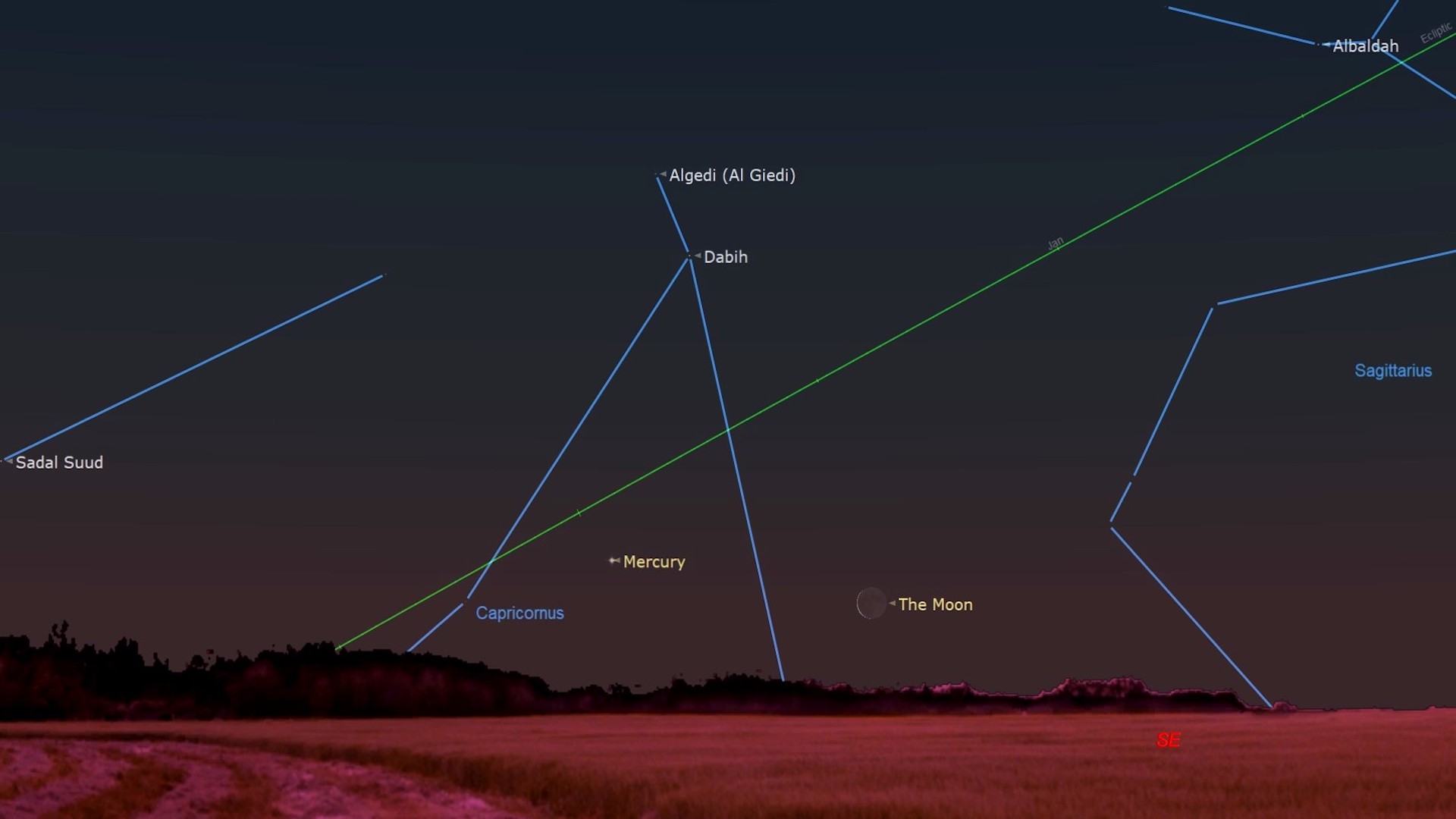

According to In the Sky from New York City the conjunction between Mercury and the moon will become visible over the horizon to the south when it rises at around 6:01 a.m. EST (1101 GMT). The celestial objects will disappear a few hours later at around 3:49 p.m. EST (2049 GMT).

During the conjunction, both bodies will be in the Capricornus constellation, the Sea Goat. The moon will be quite bright with a magnitude of -9.1, while Mercury will have a magnitude of -0.2, with the minus prefix indicating particularly bright celestial objects. The moon will be positioned three degrees to the south of Mercury.

Related: Night sky, February 2023: What you can see tonight [maps]

Looking for a telescope to see Mercury? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

In the Sky gives the right ascension of both objects as 20h52m50s and the declination of the moon as -22°45', while Mercury has a declination of -19°09'.

The planets will not be close enough in the night sky during the conjunction to be spotted together using a telescope, but the conjunction should be visible using binoculars or the naked eye.

Mercury is one of the five planets over Earth that are visible to the naked eye, which also includes Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and Venus.

This visibility comes despite Mercury's diminutive size. With a diameter of around 3,000 miles (4,800 kilometers) the planet is only around 40% larger than the moon and is just 1/3 the size of Earth. According to NASA, if Earth was the size of a nickel then Mercury would be around the size of a blueberry.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mercury is just around 36 million miles (58 million kilometers) from the sun, around 40% the distance between Earth and our star. As a result of this proximity, Mercury has a blisteringly hot surface temperature of around 800 degrees Fahrenheit (430 degrees Celsius) during the day, dropping as low as -290 degrees Fahrenheit (-180 degrees Celsius) at night.

Mercury's proximity to the sun also gives the planet a rapid orbit of just 88 Earth days, making it the fastest planet in the solar system and meaning its moniker referencing the fastest of the Roman pantheon of the gods is fitting.

If you're intending to view the daytime conjunction of the moon and Mercury, take caution not to look too close to the sun and take breaks while looking at the moon, especially if your eyes begin to sting.

If you want a glimpse of the conjunction between the moon and Mercury and don't have the optics you need, our guides for the best telescopes and best binoculars are a great place to start.

And if you're looking to snap photos of the night sky, check out our guide on how to photograph the moon, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Editor's Note: If you snap the conjunction of the moon and Mercury and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.