Astronomers just discovered a rare monster galaxy that grew rapidly in the universe's early days — and then went quiet surprisingly fast.

The newfound giant, known as XMM-2599, lies about 12 billion light-years from Earth, meaning that scientists are seeing the galaxy as it existed when the universe was quite young. (The Big Bang that created the universe occurred 13.82 billion years ago.)

“Even before the universe was 2 billion years old, XMM-2599 had already formed a mass of more than 300 billion suns, making it an ultramassive galaxy," Benjamin Forrest, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of California Riverside (UCR), said in a statement.

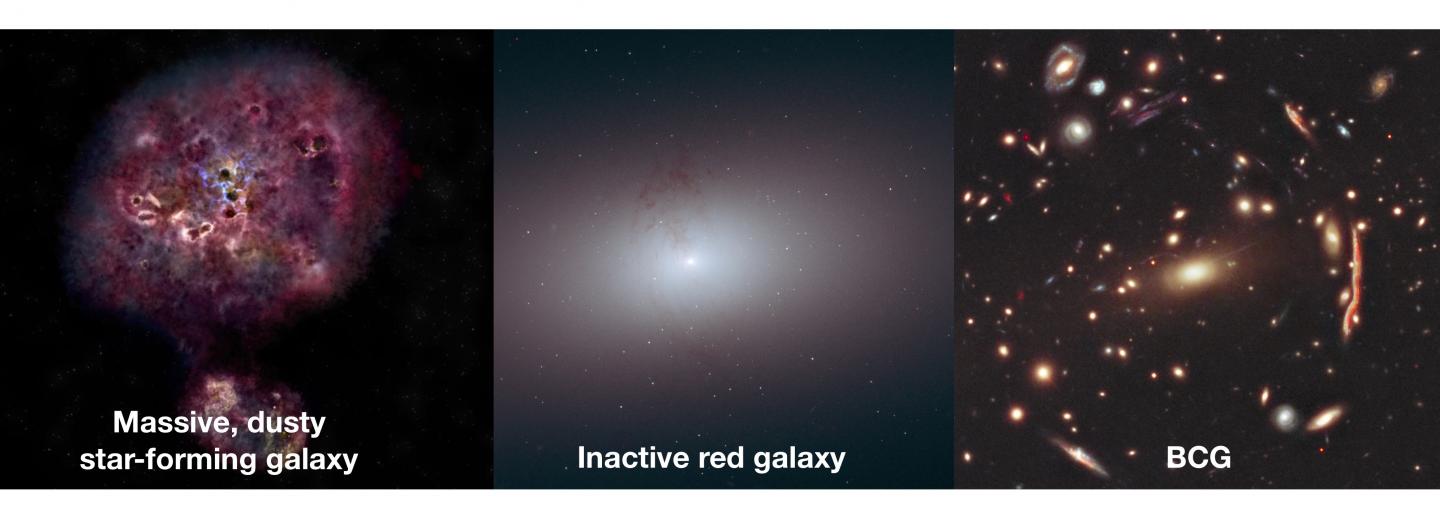

"More remarkably, we show that XMM-2599 formed most of its stars in a huge frenzy when the universe was less than 1 billion years old, and then became inactive by the time the universe was only 1.8 billion years old," added Forrest, the lead author of a new study reporting the discovery of XMM-2599.

Related: Our expanding universe: age, history and other facts

Forrest and his colleagues used an instrument called the Multi-Object Spectrograph for Infrared Exploration (MOSFIRE), which is installed on a telescope at the Keck Observatory in Hawaii. The MOSFIRE observations allowed the team to nail down XMM-2599's mass and its distance from Earth.

The researchers also determined that the galaxy created more than 1,000 suns' worth of stars every year during its activity peak. (For comparison, our Milky Way is currently forming just one solar mass of new stars annually.) But that peak is in the rearview mirror for XMM-2599; its star-birth engine has shut down, for reasons that remain unclear.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Even though such massive galaxies are incredibly rare at this epoch, the models do predict them," study co-author Gillian Wilson, a physics and astronomy professor at UCR who heads the lab in which Forrest works, said in the same statement.

"The predicted galaxies, however, are expected to be actively forming stars," Wilson added. "What makes XMM-2599 so interesting, unusual and surprising is that it is no longer forming stars, perhaps because it stopped getting fuel or its black hole began to turn on. Our results call for changes in how models turn off star formation in early galaxies."

The researchers will continue to observe XMM-2599 using Keck, in an attempt to better characterize the galaxy and investigate unanswered questions about it. The most prominent such question may concern the galaxy's fate.

"We do not know what it will turn into by the present day," Wilson said. "We know it cannot lose mass. An interesting question is what happens around it. As time goes by, could it gravitationally attract nearby star-forming galaxies and become a bright city of galaxies?"

The new study was published online Wednesday (Feb. 5) in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

- The universe: Big Bang to now in 10 easy steps

- Star quiz: Test your stellar smarts

- Keck Observatory: Cosmic photos from Hawaii's Maunakea

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.