These Gargantuan Galaxies, Hidden in Plain Sight, Could Rewrite Universe's Early Days

It's the ultimate magic of science, when using a different instrument reveals what was hidden in plain sight.

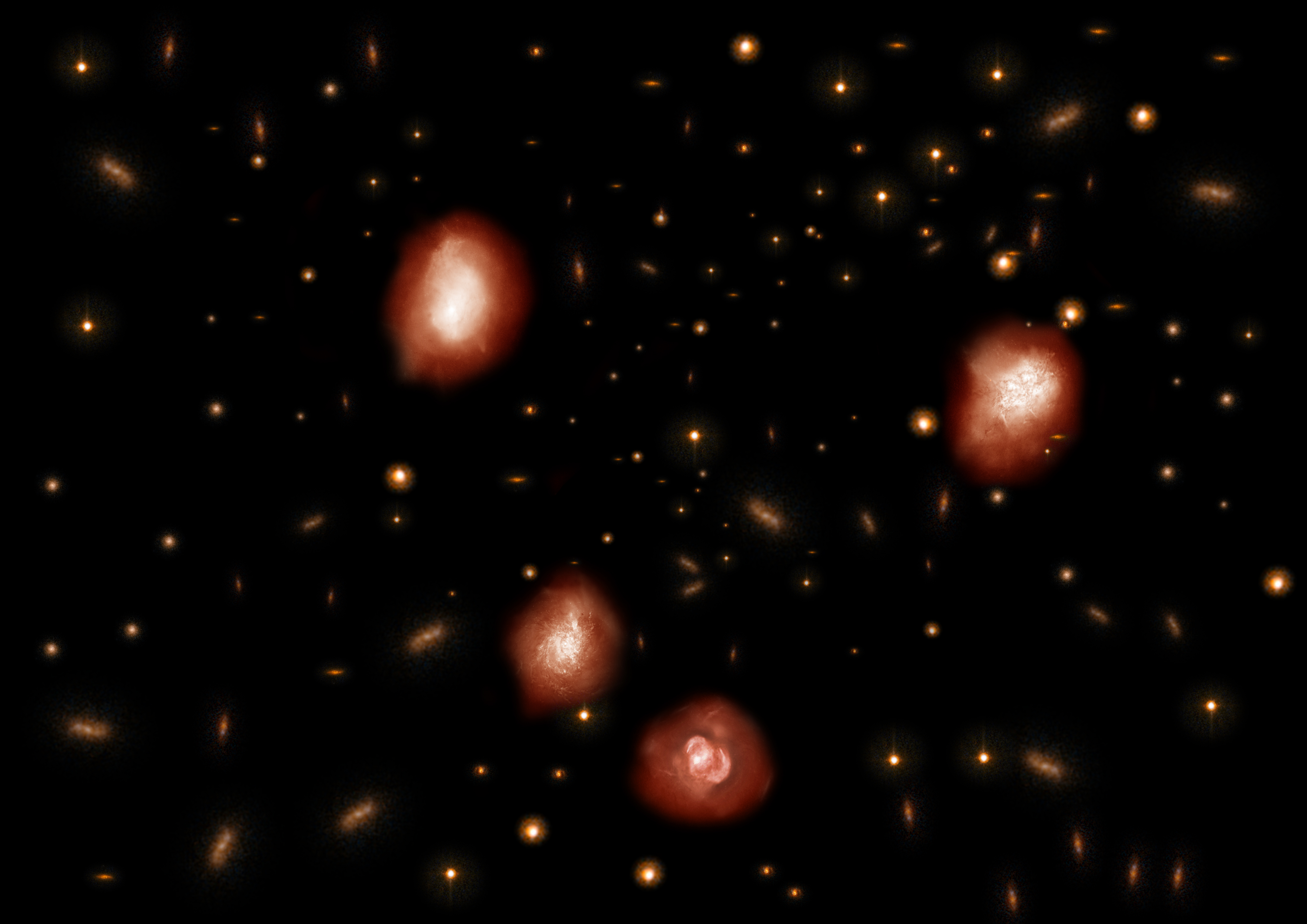

Researchers used a pair of instruments to accomplish just such a feat, spotting dozens of massive galaxies located billions of light-years away busy making huge numbers of stars. These finds could rewrite scientists' understanding of how the early universe worked — and if the galaxies were visible to humans, they would overwhelm our view of the heavens, researchers said.

"For one thing, the night sky would appear far more majestic. The greater density of stars means there would be many more stars close by appearing larger and brighter," lead researcher Tao Wang, an astronomer at the University of Tokyo, the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission, and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, said in a statement. "But conversely, the large amount of dust means farther-away stars would be far less visible, so the background to these bright, close stars might be a vast, dark void."

Related: Meet ALMA: Amazing Photos from Giant Radio Telescope

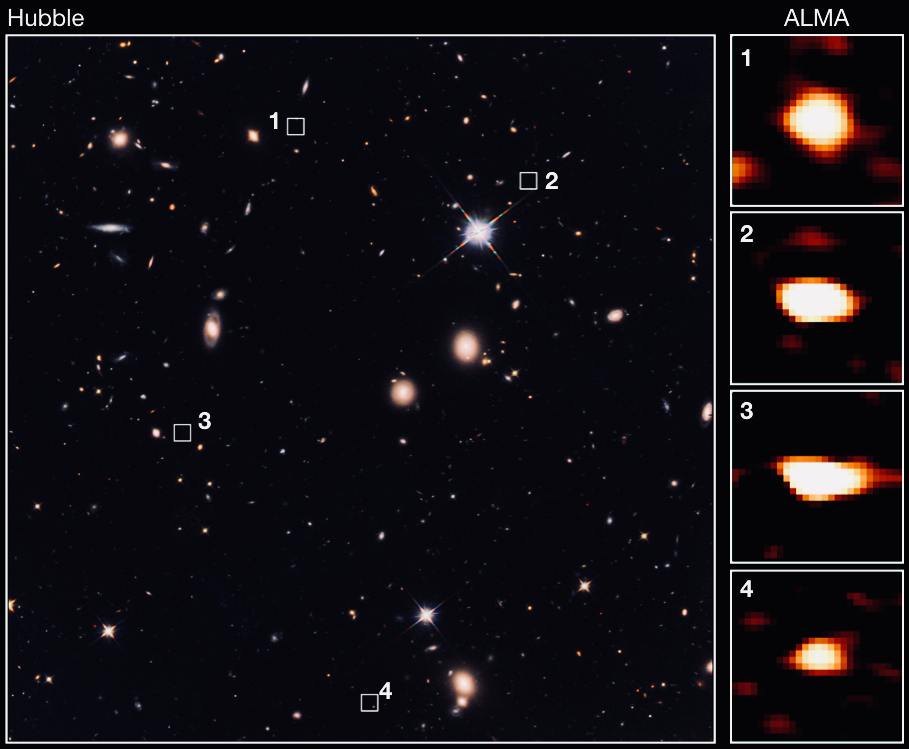

But humans will never be able to see these galaxies directly, which is why it took so long for scientists to find the objects in the first place. Because of their distance from Earth and the type of light they produce, they are invisible to the Hubble Space Telescope, which sees approximately the same types of light as our eyes do.

Instead, the researchers turned first to data gathered by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, identifying 63 previously unknown objects. But the team couldn't quite make out what those objects were. So the astronomers turned to the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), a spread of radio dishes in Chile. The instrument established that 39 of the objects were massive galaxies each producing huge numbers of stars, the equivalent of 1,000 of our suns every year.

That finding is particularly intriguing, because these objects are so far away that scientists are seeing them as they were in the first 2 billion years of the universe. (Gazing at very distant objects like these galaxies automatically implies looking back in time, because light requires time to travel across such great distances.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists knew that there should be some objects like these out there, and the researchers said that as these galaxies age, they should turn into massive elliptical galaxies like those we see closer to the Milky Way. But the team found 10 times more of these young galaxies than the researchers expected to see based on current ideas about how the early universe worked.

In particular, the findings suggest that current estimates of the amount of dark matter in the universe might be wrong, since those estimates make it unlikely that so many large objects would appear early in the universe's life.

The astronomers behind the new research said they hope the James Webb Space Telescope will provide better data about additional galaxies that Hubble can't see. These observations could help scientists update their theories about the universe's early days.

The research was described in a paper published today (Aug. 7) in the journal Nature.

- How Galaxies Are Classified by Type (Infographic)

- The Best Hubble Space Telescope Images of All Time!

- Gallery: 65 All-Time Great Galaxy Hits

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.