Could Volcanic Activity Allow Water Beneath the Martian Polar Ice?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

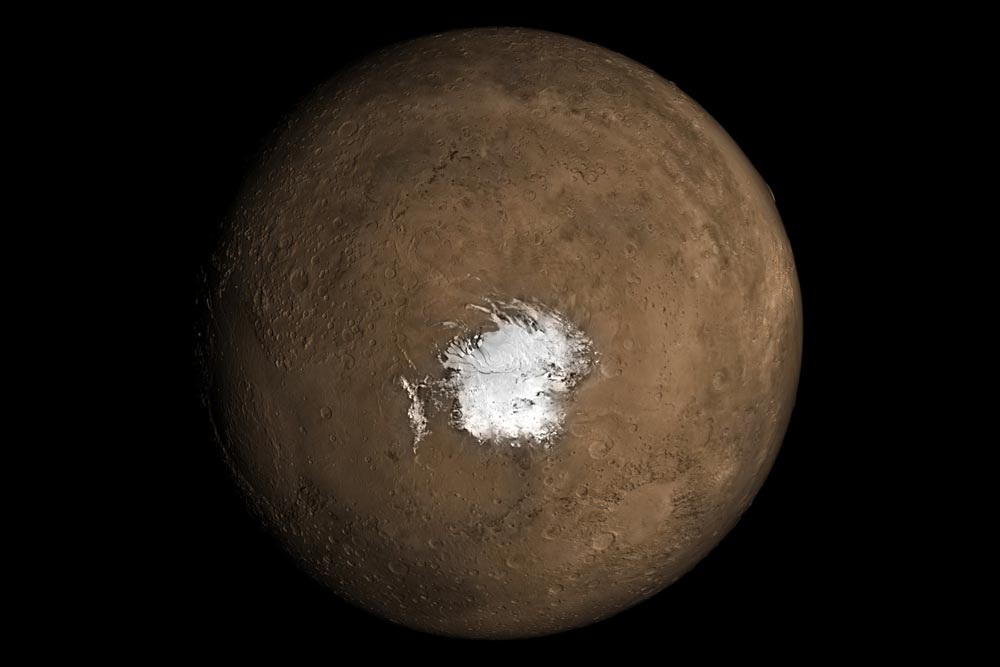

If liquid water indeed exists under the south polar ice cap of Mars, it has to be due to volcanic activity, a new study suggests.

The researchers behind the new work argued that there needs to be an underground source of heat to melt ice under an ice cap — although they didn't weigh in on whether that liquid water (or the volcanic heat, for that matter) actually exists on Mars.

The new study follows up a controversial finding published in the journal Science last July, in which a European Space Agency orbiter, Mars Express, spotted signs of what could be a slurry or a liquid-water lake under the polar ice. At the time, the idea was that a high concentration of salt could keep the water from freezing despite Mars' chilly temperatures. What's strange about that finding is that NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter didn't see any sign of a lake, even though that craft's ground-penetrating radar vision should theoretically be able to spot such a feature. [Photos: Red Planet Views from Europe's Mars Express]

If the water is indeed there, the new study said, a magma chamber must have formed sometime in the past few hundred thousand years under the Martian surface in order to melt the water; salt wouldn't do the trick. (The scientists also pointed out that if the water does not exist, the magmatic activity would also be absent.)

"Different people may go different ways with this, and we're really interested to see how the community reacts to it," co-lead author Michael Sori, an associate staff scientist in the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona, said in a statement from the American Geophysical Union (publisher of Geophysical Research Letters, the journal in which the new study appeared.)

If volcanic activity is happening on Mars, scientists say it's a strong sign that Mars is active — and a good omen for finding life on the Red Planet, as well. (A new NASA mission called InSight is examining the possibility of current volcanic activity on the Red Planet, but the instrument only just deployed its seismometer shield and results will be months or years in coming.) Life would require a source of water, a source of energy and some sort of protection from the radiation bathing Mars.

"We think that if there is any life, it likely has to be protected in the subsurface from the radiation," said Ali Bramson, the paper's other co-lead and a postdoctoral research associate at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, in the same statement. "If there are still magmatic processes active today, maybe they were more common in the recent past and could supply more widespread basal melting. This could provide a more favorable environment for liquid water and thus, perhaps, life."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

On Earth, it's common to see liquid water under ice sheets, but scientists know why this occurs: because our planet produces enough internal heat to melt ice that rubs against the Earth's crust. But Mars is much cooler than Earth; it is farther from the sun and smaller than our planet, so it generates less internal heat. On Mars, it's unclear what phenomenon could melt its two polar ice sheets, which are each a couple of kilometers thick.

The new study started with the assumption that liquid water could exist under the Martian polar ice, then modeled how much heat is generated in the planet's interior to determine whether there is enough salt at the bottom of the ice cap to melt the ice. Salt lowers the freezing point of water and has been used in Mars modeling before to argue that dark streaks appearing on crater walls came from liquid water. Some scientists say salt allowed a briny water to flow down the crater, while others argue the features represent dry dust flows. [Mars' South Pole May Hide a Large Underground Lake]

In the new paper, the scientists discovered that salt alone couldn't raise the temperature of water high enough to melt ice if salt is nestled underneath the ice cap. So, an additional heat source is required — hence, the volcanic idea. Perhaps, the paper suggested, magma flowed from the inside of Mars to near the surface roughly 300,000 years ago. The magma didn't erupt, but instead pooled in a chamber just underneath the surface. Over the eons, this magma chamber gradually cooled off and the evaporated heat melted the ice at the bottom of the south polar sheet, this scenario continues.

Mars hosts numerous old volcanoes, including Olympus Mons, the largest volcano in the solar system. But there's no compelling evidence showing that these volcanoes are active. In fact, many scientists argue that volcanism on Mars could have stopped millions of years ago, according to the journal's statement.

Jack Holt, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona, said the paper does address one reason why water could exist under the south polar ice cap. However, Holt, who talked to the authors before they submitted the new paper for publication but did not take part in the research, added that more research is required to better narrow down the answer.

"I think it was a great idea to do this type of modeling and analysis, because you have to explain the water, if it's there, and so it's really a critical piece of the puzzle," Holt said in the statement. "The original paper [about the polar water find, in Science] just left it hanging. There could be water there, but you have to explain it, and these guys did a really nice job of saying what is required and that salt is not sufficient."

The new research is described in a paper published yesterday (Feb. 12) in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.