Mars sports massive hidden plume of searing rock

"Our study demonstrates that Mars is not dead."

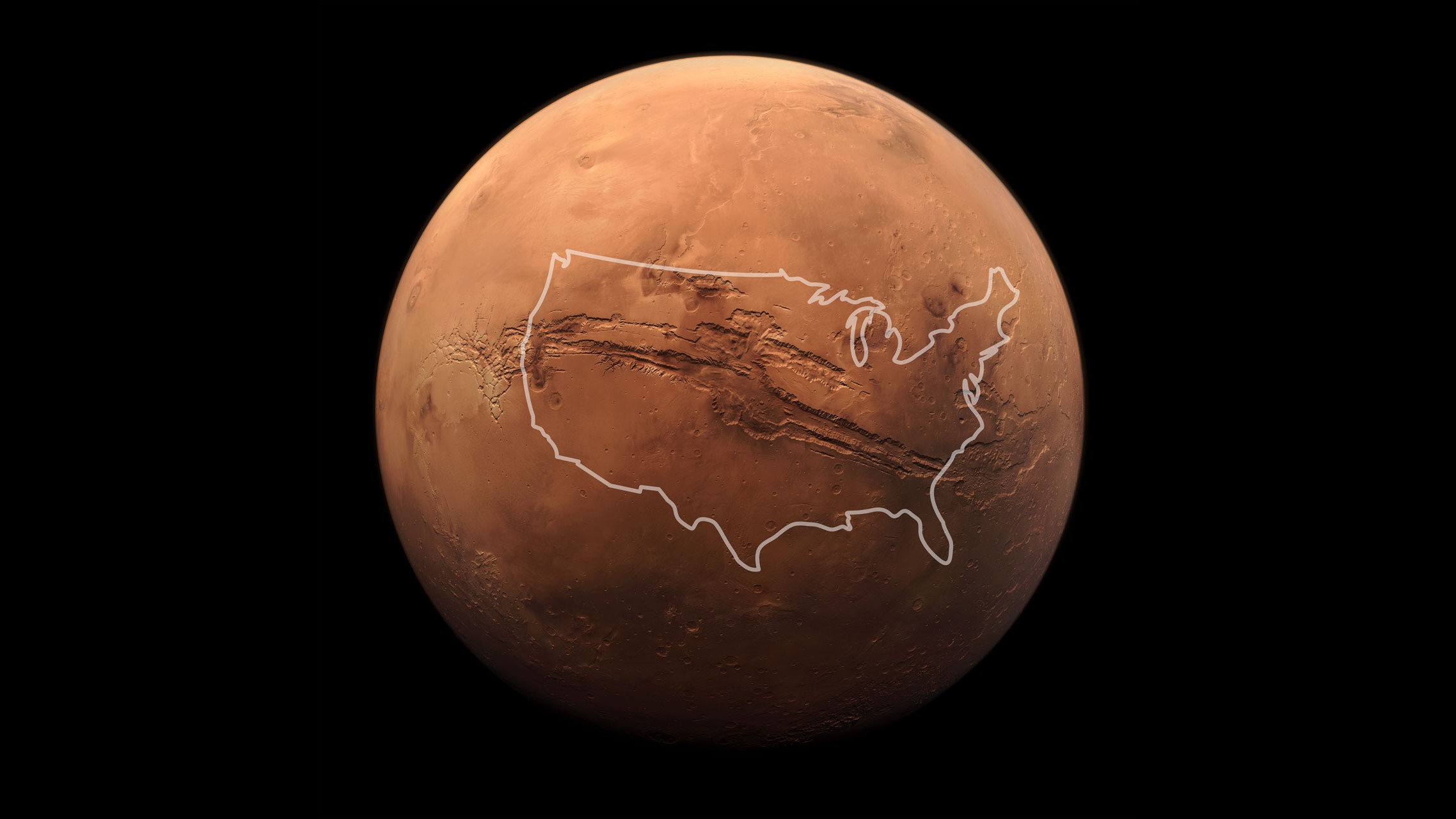

A plume of searing hot rock as wide as the continental U.S. is rising up from near the core of Mars and might help explain recent volcanism and earthquakes seen at the Red Planet, scientists say.

Most volcanism on Mars occurred during the first 1.5 billion years of its history, leaving behind giant monuments such as Olympus Mons, the tallest mountain in the solar system. However, scientists had largely thought Mars cooled since then, becoming essentially dead for the past 3 billion years or so. But in recent years, scientists have seen hints of geologic activity after all, and now scientists have found a mushroom-shaped pillar of scorching, buoyant rock below a region called Elysium Planitia that might explain recent findings.

"Our study demonstrates that Mars is not dead," study lead author Adrien Broquet, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona at Tucson, told Space.com.

Related: Magma on Mars may be bubbling underground right now

The narrative around Mars' recent geology began to change with a 2021 study that found evidence that Mars might still be volcanically active, with signs of an eruption within the past 53,000 years or so. Using data from satellites orbiting Mars, that research discovered a previously unknown smooth, dark volcanic deposit covering an area slightly larger than Washington, D.C. The deposit surrounds one of the cracks that makes up the 800-mile-wide (1,300 kilometers) system of young fissures known as Cerberus Fossae. This area lies within the relatively featureless plains known as Elysium Planitia, located in the northern lowlands close to the Martian equator.

In addition, NASA's InSight lander has detected hundreds of quakes on the Red Planet, with most of the larger of those marsquakes stemming from Cerberus Fossae. All in all, the probe's findings suggest that the level of seismic activity on Mars falls between that of the moon and of Earth.

In the new research, scientists developed geophysical models based on geological, terrain and gravity data from Elysium Planitia. They found evidence that the entire area sits over a mantle plume — a column of hot rock ascending from deep within Mars to sear overlying material like a blowtorch. Broquet said this mantle plume formed about 930 miles (1,500 km) below the surface, at the interface between the core of Mars and the mantle layer, which itself rests between the Martian core and crust.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We find this giant plume to be about the size of the continental USA, about 2,500 miles (4,000 km) — which, for a planet smaller than Earth, is even more enormous," Broquet said.

Although this is the first mantle plume scientists have found on Mars, geologists have long known of mantle plumes on Earth. For instance, the island chain of Hawaii formed as the Pacific tectonic plate has slowly drifted over a mantle plume.

The material in a mantle plume is buoyant compared to surrounding rock. "It is lighter, so it floats and migrates upward, similar to what you can observe in a lava lamp, where heated oil rises up," Broquet said.

The researchers suggested the center of the newly detected Martian mantle plume is located precisely below Cerberus Fossae. They estimated that the plume is about 170 to 520 degrees Fahrenheit (95 to 285 degrees Celsius) hotter than its surroundings.

The researchers found that the mantle plume has pushed the Martian crust up by more than a mile (1.6 km), bringing hot magma to the Red Planet's surface and driving the marsquakes that InSight has detected.

"Not only there is young volcanism in this area, but we see that this volcanism is part of a recent resurgence in activity," Broquet said. "Before about 100 million years ago, the last major activity in this region was nearly 3 billion years ago. So again, something must have happened to cause this volcanic resurgence, and that something is the mantle plume."

Broquet said he suspects that Elysium Planitia was the only region on Mars with an active mantle plume, although a second plume might hide under Tharsis. Tharsis is a region 3,000 miles (4,800 km) wide near the equator in the western hemisphere of Mars that holds the biggest volcanoes in the solar system and where scientists have detected recent and ongoing volcanic activity, he noted.

However, there may be explanations for volcanic activity in Tharsis other than a mantle plume, he said. For instance, the crust there is very thick, and so may have trapped heat, helping keep rock there molten. In contrast, "in the Elysium Planitia region, where we found the plume, the crust is known to be significantly thinner, and so we had to invoke another mechanism — that is, the plume — to induce the volcanism," he said.

Active worlds

All in all, these findings suggest that Mars is the third body in the inner solar system, after Earth and Venus, where mantle plumes are currently active.

"We used to think that InSight landed in one of the most geologically boring regions on Mars — a nice flat surface that should be roughly representative of the planet's lowlands," Broquet said. "Instead, our study demonstrates that InSight landed right on top of an active plume head."

The new findings may also have implications in the search for life on Mars, the researchers said. The area where they discovered the plume also has the most recent evidence for liquid water flowing on the surface of the Red Planet. Since there is life virtually everywhere there is water on Earth, scientists often focus the search for extraterrestrial life on sites that possess water.

"Water ice is still thought to be present in Mars' subsurface, and so, if the plume is still providing heat, which we think to be the case, liquid water pockets or aquifers could be present next to magma chambers in the crust of the Elysium Planitia region," Broquet said. "On Earth, microbes flourish in environments like that. Therefore, I would say that the plume has implications for the astrobiological potential of present-day Mars. One next step could be to estimate if these aquifers are present and where they could be."

It remains unclear how a mantle plume might have formed recently on a cooling Mars.

"A plume usually takes a few hundreds of millions of years to rise from the core-mantle boundary to the surface," Broquet said. "Once it reaches the surface, our experience on Earth tells us that the plume remains active for a few tens to a few hundreds of million years. So geologically speaking, this plume formed and reached the base of the crust fairly recently, which is what is surprising. It is not an old plume that has survived Mars' history."

Broquet noted that scientists once thought the moon was also geologically dead. "Because of its small size, it was expected to have cooled faster than the Earth," he said. "However, seismic data recorded during Apollo era have been used to show that the core of the moon is molten, and this was a big surprise. The moon is not cold and dead — it still has some heat within."

Akin to these findings on the moon, "our discovery is a paradigm shift for our understanding of how Mars evolved," Broquet said. "Such a large mantle plume is not predicted by current model of Mars' thermal evolution. Future studies will need to invoke new mechanism and a new geologic history to find a way to account for a very large mantle plume that wasn't expected to be there."

All in all, "there are a lot of fundamental physics in the interior of a planet that we, obviously, don't understand," Broquet said. "Same as when we thought the moon to be dead."

The research is described in a paper published Monday (Dec. 5) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us