NASA: No current plan for return of space station parts for museums

"NASA's lack of a sufficient process to identify its heritage assets can jeopardize the preservation of irreplaceable historic property."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A recently-released plan for how NASA will dispose of the International Space Station makes no mention of preserving historically-significant components from the orbiting complex. But it is not just an omission from a report: the space agency says it has no current plans to return potential artifacts to Earth.

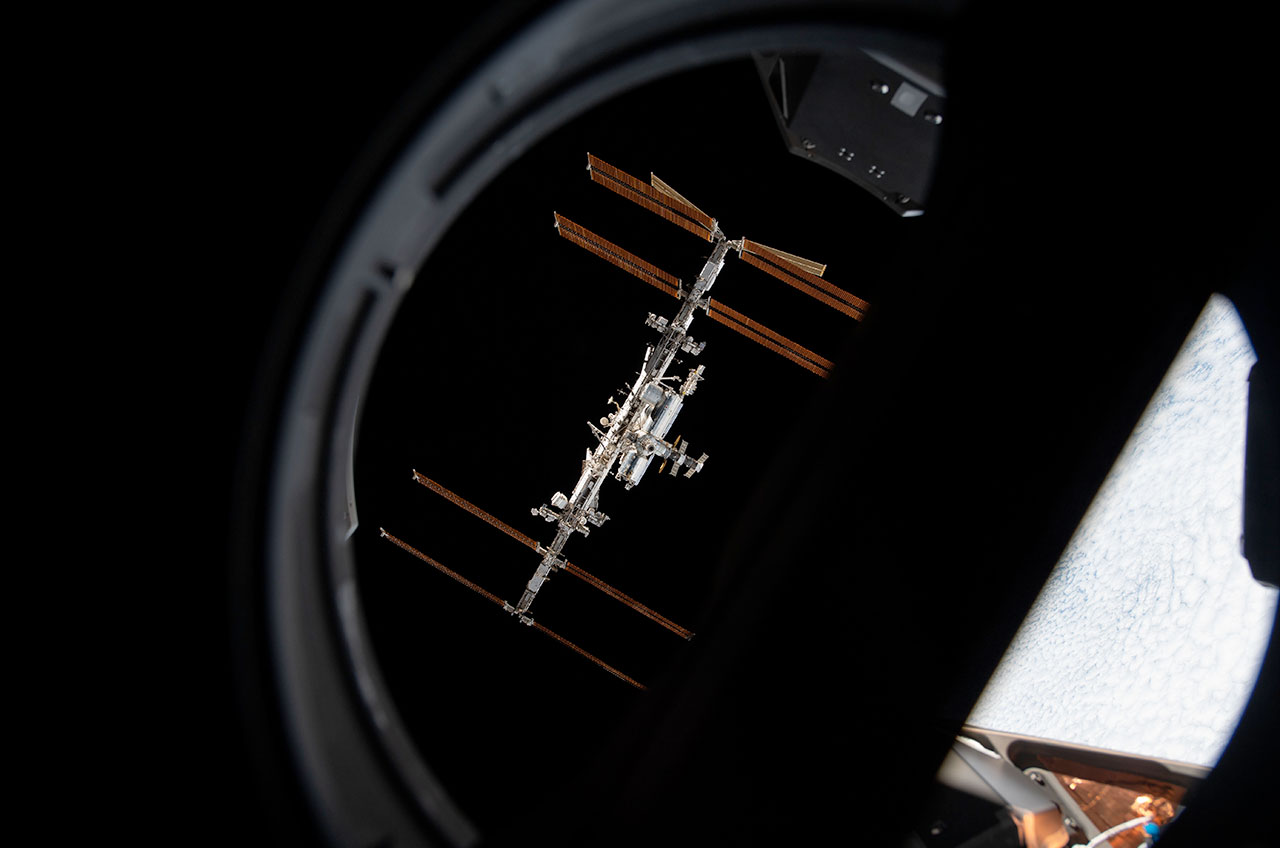

The International Space Station (ISS) Transition Report, which NASA published on its website in January, outlines the budget and logistics needed to safely de-orbit the football-field-wide space station by directing it into a controlled but destructive re-entry into Earth's atmosphere over an uninhabited area of the South Pacific Ocean. Any surviving parts would fall into and sink around "Point Nemo," a region traditionally used for spacecraft disposal given that it is the farthest from any land.

The report, which assumes a 2030 end-of-life for the space station, also explains what NASA wants to do with the complex in the years that it has left. The goals include using the complex to perform scientific research, expand the burgeoning commercial space industry and enable international cooperation. Another of the objectives, which NASA titles "Inspire Humankind," calls for engaging the public "through different platforms to communicate the values that [the] ISS brings to the nation and the world."

Related: The International Space Station will eventually die by fire

That last goal, though, appears to ends when the space station meets its end. The document says nothing about saving parts of the ISS as museum artifacts that could continue to inspire the public for many more decades to come, well beyond the station's own lifespan.

Posterity not a priority

"There has not been discussion in the International Space Station Program to return items solely for display," NASA said in a statement, responding to an inquiry by collectSPACE.com. "No down mass has been set aside at this time on upcoming cargo flights as we remain focused on maximizing use of the International Space Station."

"Any decision to return artifacts from [the] space station would happen at a later date based on any available cargo space as we will prioritize science return," the statement concluded.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NASA's response suggests that historical preservation is not one of its priorities, despite its transition report listing science and inspiration as equally important goals. It also means that any future decisions made to save items will have be opportunistic, coming only after the program's other needs are met. This did not need to be the case.

In preparing the transition plan, NASA projected the budget it needed for several cargo vehicles to carry out the safe de-orbit of the space station. It gave no similar consideration, though, for using other supply craft to return historically-significant or representative parts to Earth.

The lack of advance planning and resource allocation when it comes to identifying "heritage assets" on board the space station reflects an issue that the NASA Office of Inspector General (OIG) warned about in a 2018 audit of NASA's historical property. In that report, the OIG found that NASA representatives were "unable to explain who was responsible for designating an item as a heritage asset or how or why an item was designated a heritage asset."

collectSPACE made multiple requests of NASA to speak with the official who is responsible for considering the preservation of parts of the space station. No such individual was identified.

"NASA's lack of a sufficient process to identify its heritage assets can jeopardize the preservation of irreplaceable historic property," the OIG cautioned in its report.

It all comes down to this

In a follow up to its transition report, NASA addressed some of the questions it received about the plan, including why disassembling and returning to Earth the complete modules and large components that comprise the International Space Station was not feasible.

"Preserving the station in a museum presents significant logistical and financial challenges," the space agency wrote in an update posted to its website. "Any disassembly effort to safely return individual components would face significant logistical and financial challenges, requiring substantial work by astronauts and ground support personnel as well as a spacecraft with a capability similar to the space shuttle's large cargo bay,"

The space shuttle fleet was retired in 2011. Today, the only vehicle with significant down mass capability is the SpaceX Dragon, which can bring up to 6,614 pounds (3,000 kg) back to Earth.

NASA's update also addressed the reuse of equipment, stating that while it will assess what internal components could be of interest to the privately-operated space stations that take over for the ISS, there are no current proposals from the commercial providers requesting such.

"Much of the structural hardware on station was designed and built in the late 1990's and 2000's, whereas new commercial destinations will benefit from more recent technology advancements," NASA stated.

The transition report identifies the annual budget of de-orbiting the ISS, "including the cost associated with three [Russian expendable] Progress vehicles needed to support that effort" to top out at about $1.5 billion during its peak year, which as of now is projected to be 2028. The report does not address the cost of setting aside volume on an Earth-bound SpaceX Dragon capsule or other returning spacecraft, but a price chart for the commercial use of the space station (while it is still in orbit) sets the rate of landing passive cargo at $40,000 per 2.2 pounds (1 kg).

Were NASA to later decide to bring back parts of the space station for museum display, a long-standing agreement would provide the Smithsonian Institution with first right of refusal. The National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. has a gallery devoted to "Moving Beyond Earth," which includes the space station, but the number of artifacts it has from program are limited.

"The Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum has a strong history of working collaboratively with NASA as operational programs have wound down in the past, selecting objects and artifacts to preserve what has been important for history," said Margaret Weitekamp, chair of the Space History department at the National Air and Space Museum. "Right now, it may be premature to speculate on decisions that will become more clear in nine years when they are more immediate. The International Space Station continues to be dynamic and vibrant, with a lot of good science yet to come."

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2022 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.

In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.