Hubble Telescope finds surprising source of brightest fast radio burst ever

The FRB flashed farther away from Earth than any other previously observed.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

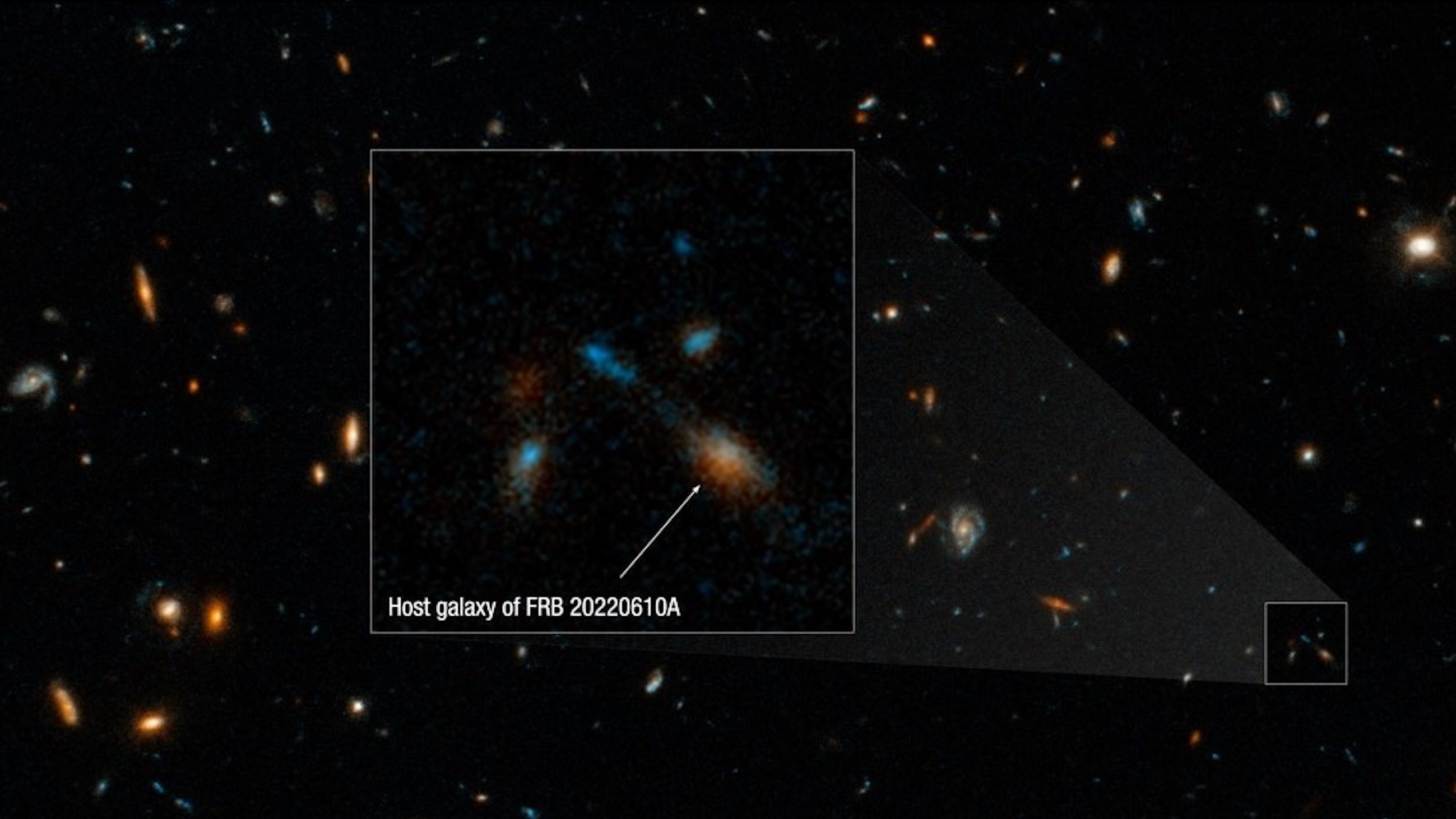

The brightest fast radio burst ever observed emerged from a group of ancient galaxies that appear to be merging, observations by the Hubble Space Telescope have revealed.

The finding surprised astronomers, as the vast majority of known fast radio bursts (FRBs) has come from single galaxies much closer to Earth.

The FRB in question brightened the radio sky above Earth on June 10, 2022, and was first detected by the Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder radio telescope in Western Australia.

Article continues belowRelated: What are fast radio bursts?

FRBs are not rare; sensitive radio telescopes all around the world detect them almost daily. These brief explosions of cosmic radio waves last only a fraction of a second but can briefly outshine the radio output of an entire galaxy.

The fast radio burst of June 10, 2022, however, was in a league of its own. Subsequent observations by the Very Large Telescope in Chile suggested that the FRB came from very far away and packed four times more energy than other previously observed FRBs.

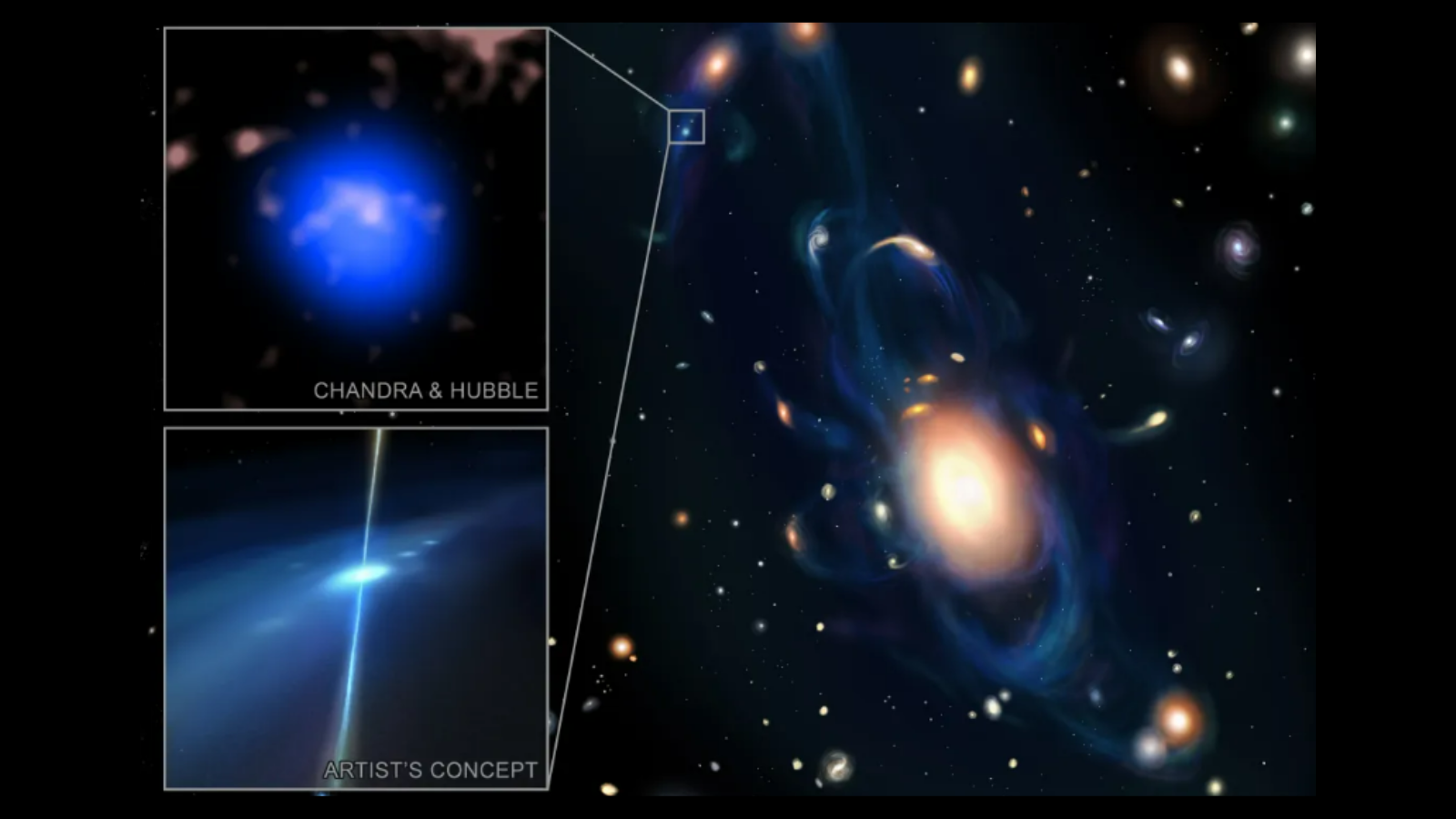

Scientists still don’t know what causes FRBs, but they think the process must involve some form of interaction between extremely massive and compact objects such as black holes or neutron stars.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Most previously observed FRBs have been traced back to individual, isolated galaxies. But the search for the source of the super-powerful event observed in June 2022 turned out unexpected results. Observations of the source region by the venerable Hubble Space Telescope revealed that the flash emerged not from a single galaxy but from a group of very old galaxies that appear to be merging.

The seven galaxies in the source region are about five billion years old, more than one-third the age of the universe.

"It required Hubble's keen sharpness and sensitivity to pinpoint exactly where the FRB came from," astronomer Alexa Gordon of Northwestern University in Illinois, the lead researcher behind the observations, said in a statement. "Without Hubble's imaging, it would still remain a mystery as to whether this was originating from one monolithic galaxy or from some type of interacting system. It's these types of environments — these weird ones — that are driving us toward better understanding the mystery of FRBs."

The quest for the origin of fast radio bursts continues. Researchers hope for major breakthroughs when new, more powerful radio telescopes come online later this decade, such as the Square Kilometer Array telescope that is currently being built on sites in Australia and South Africa.

"We just need to keep finding more of these FRBs, both nearby and far away, and in all these different types of environments," said Gordon.

The observations were presented at the 243rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society in New Orleans, Louisiana, on Tuesday (Jan. 9).

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.