Astronomers discover record haul of 25 new repeating 'fast radio bursts'

The discovery doubles the known population of these repeating super-energetic cosmic explosions.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Astronomers have doubled the known number of repeating rapid bursts of powerful radiation emanating from distant galaxies outside the Milky Way.

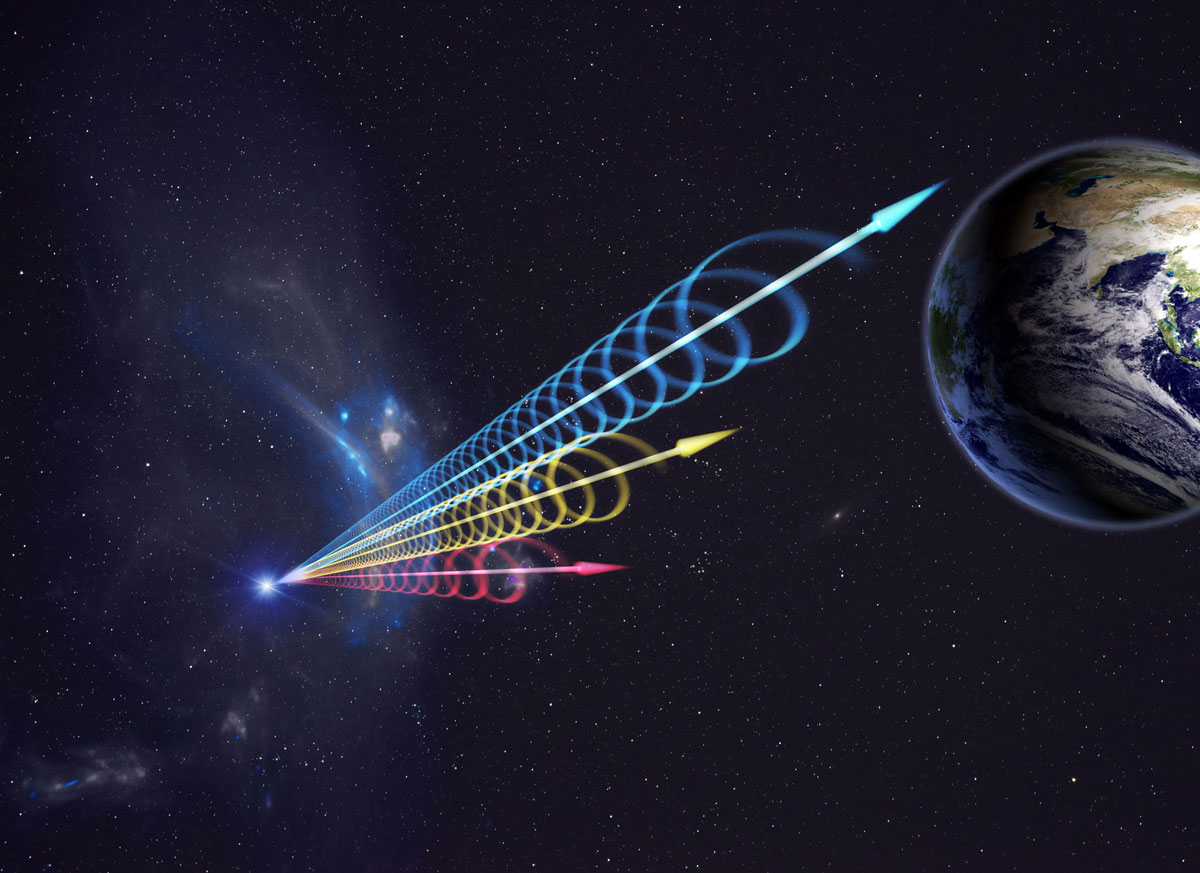

These blasts, known as fast radio bursts (FRBs), are so powerful they can outshine the entire galaxy from which they emerge. But despite this incredible power, the origins of FRBs are mysterious.

In a new study, a team led by astronomers from the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME)/FRB Collaboration and the University of Toronto found 25 new repeating FRBs, bringing the total known to 50. This could lead scientists to the discovery of what causes these bursts and also suggests that many more FRBs could eventually repeat than previously thought, team members said.

Related: Curious cosmic coincidence could help explain fast radio burst mystery

Astronomers have discovered many FRBs over the last decade, but the vast majority of these have been non-repeating and were only seen to "burst" once. Only a small fraction have been seen to repeat. This has led astronomers to question if repeating FRBs and non-repeating FRBs come from the same sources.

The fact that these two populations of FRBs seem to have different characteristics — including how long they last and the range of frequencies they are seen across — also points to their varied origins. Key to confirming this is the discovery of more repeating FRBs, which the team involved in this research did by developing a new set of statistical tools and combing through data to analyze every repeating FRB ever seen, including ones that aren't immediately obvious.

"We can now accurately calculate the probability that two or more bursts coming from similar locations are not just a coincidence," study team member Ziggy Pleunis, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Toronto's Dunlap Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics, said in a statement. "These new tools were essential for this study, and will also be very useful for similar research going forward."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Radio telescopes like CHIME, which is located at the Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory, near Penticton, Canada, have been integral to the detection of FRBs. In the past few years, observations have gone from tens to thousands, and much of this is thanks to CHIME's ability to scan the entire northern sky every day.

"That's how CHIME has an edge over other telescopes when it comes to discovering FRBs," Pleunis said.

One surprising aspect of this new research is the discovery that many repeating FRBs are surprisingly inactive, producing under one burst per week during CHIME's observing time. Pleunis believes that this could be because these FRBS haven't yet been observed long enough for a second burst to be spotted.

Repeating FRBs are extremely useful to astronomers as they present the opportunity to observe the same FRB source with telescopes other than the one that initially sighted them, allowing these mysterious events to be viewed in finer detail.

"It is exciting that CHIME/FRB saw multiple flashes from the same locations, as this allows for the detailed investigation of their nature," study team member Adaeze Ibik, a University of Toronto Ph.D. student, said in the same statement. "We were able to hone in on some of these repeating sources and have already identified likely associated galaxies for two of them."

The team's findings could also have implications beyond helping narrow down the hunt for the origins of FRBs.

"FRBs are likely produced by the leftovers from explosive stellar deaths. By studying repeating FRB sources in detail, we can study the environments that these explosions occur in and understand better the end stages of a star's life," Pleunis said. "We can also learn more about the material that's being expelled before and during the star's demise, which is then returned to the galaxies that the FRBs live in."

The new study was published online today (April 26) in The Astrophysical Journal.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.