New Hubble Constant Measurement Stokes Mystery of Universe's Expansion

A new measurement suggests that the universe is expanding faster than we thought.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Scientists have come up with a new measurement for the expansion rate of the universe, leading to questions regarding the discrepancies between current observations and the model of the universe that astronomers have relied on for years.

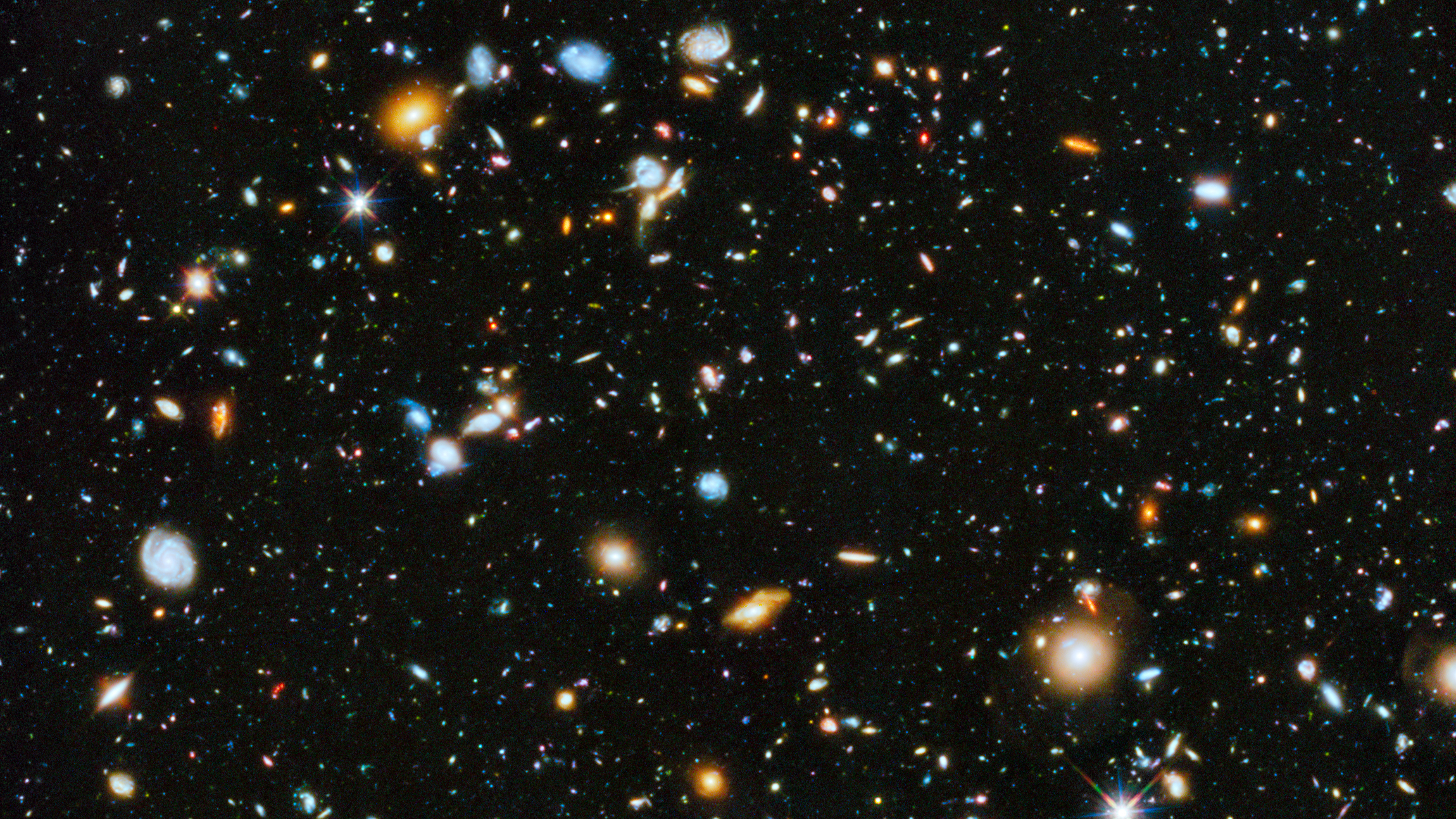

New observations made using the Hubble Space Telescope indicate that the universe is expanding at the rate of just under 43 miles per second (70 kilometers per second) per megaparsec, a distance equivalent to 3.26 million light-years.

This expansion rate is slightly slower than previous measurements taken by Hubble and the European Space Agency's (ESA) Gaia satellite, which indicated that the universe is expanding at 45.6 miles per second (73.5 km/s) per megaparsec. Another earlier measurement by ESA's Planck satellite has shown that the universe is expanding at a slightly slower rate of 41.6 miles per second (67.4 km/s) per megaparsec.

Related: In Photos: Universe's Expansion Revealed by Quasars & Cosmic Lenses

To measure the universe's expansion rate — a number known as the Hubble constant — astronomers typically look at stars and galaxies to see how fast they seem to be moving apart. The Planck measurement, on the other hand, is based on the cosmic microwave background, or leftover radiation from the Big Bang. By looking for these "echoes" of the Big Bang, Planck provided clues about what the universe looked like in its infancy and enabled predictions of how the universe would have likely evolved to reach its current expansion rate, Hubble scientists said in a statement.

The new study puts into question predictions made about the universe that have in turn formed our current models regarding the universe's age, its origin and how it will evolve over time.

"The Hubble constant is the cosmological parameter that sets the absolute scale, size and age of the universe," Wendy Freedman, a professor of cosmology at the University of Chicago and lead author of the new study, said in the statement. "It is one of the most direct ways we have of quantifying how the universe evolves."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This new evidence suggests that the jury is still out on whether there is an immediate and compelling reason to believe that there is something fundamentally flawed in our current model of the universe," Freedman said.

Earlier in 2001, Freedman led another study that used distant stars called Cepheid variables to measure the Hubble constant at 45 miles per second per megaparsec (72 km/s/Mpc). Cepheid variables are pulsating stars that rapidly vary in brightness over time, and astronomers can determine their distances from Earth based on their changing luminosity.

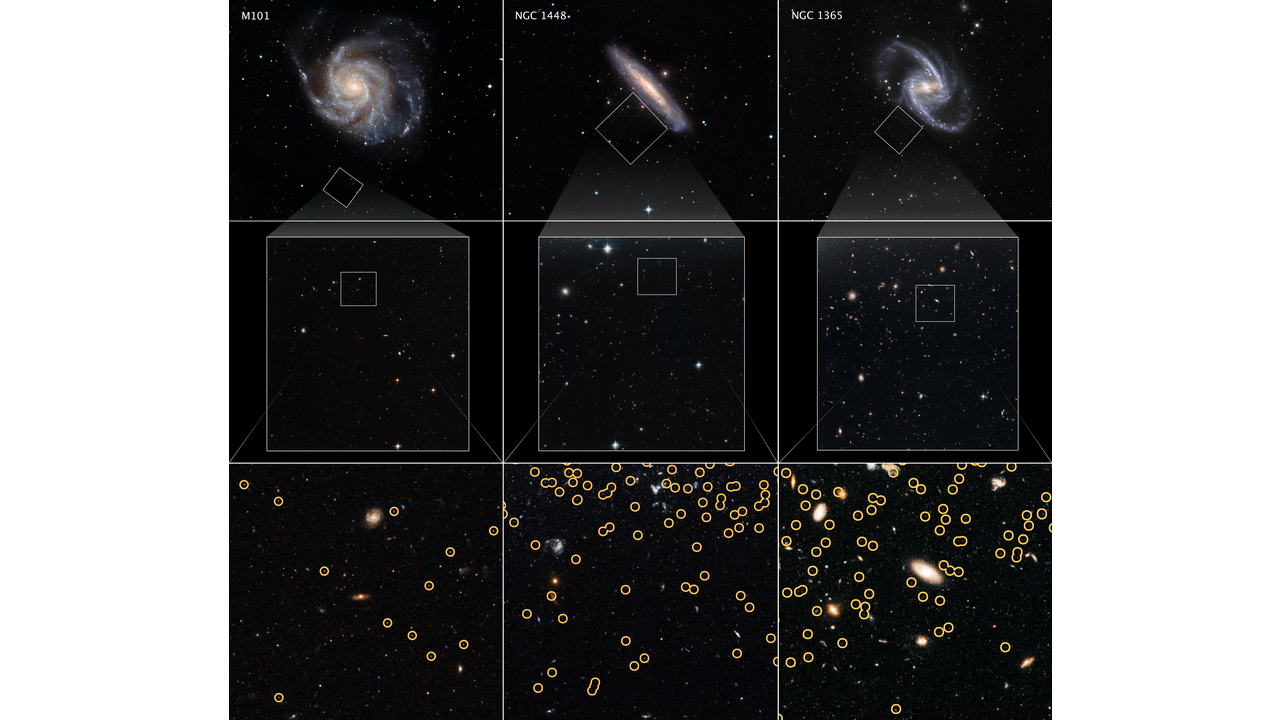

However, this new study used red giant stars in nearby galaxies to measure the expansion rate. Red giants are nonvariable stars that all reach the same peak luminosity toward the end of their life cycle. Measuring the brightness of red giant stars at this stage of stellar evolution can help scientists figure out their distance, according to the statement.

Freedman's team chose this different approach to measuring the Hubble constant in hopes of figuring out why earlier measurements using other methods have been so inconsistent. "Our initial thought was that if there's a problem to be resolved between the Cepheids and the cosmic microwave background, then the red giant method can be the tie-breaker," Freedman said.

"Naturally, questions arise as to whether the discrepancy is coming from some aspect that astronomers don't yet understand about the stars we're measuring, or whether our cosmological model of the universe is still incomplete," Freedman said. "Or maybe both need to be improved upon."

The study was accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

- Gravitational Waves Could Solve Hubble Constant Conundrum

- Exotic 'Early Dark Energy' Could Be the Missing Link of Universe's Expansion

- Universe's Expansion Rate Is Different Depending on Where You Look

Follow Passant Rabie on Twitter @passantrabie. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Passant Rabie is an award-winning journalist from Cairo, Egypt. Rabie moved to New York to pursue a master's degree in science journalism at New York University. She developed a strong passion for all things space, and guiding readers through the mysteries of the local universe. Rabie covers ongoing missions to distant planets and beyond, and breaks down recent discoveries in the world of astrophysics and the latest in ongoing space news. Prior to moving to New York, she spent years writing for independent media outlets across the Middle East and aims to produce accurate coverage of science stories within a regional context.