Book excerpt: 'How to Die in Space' on the beauty and danger of nebulas

Sure, space looks pretty, but just because it sparkles doesn't make it welcoming.

Because, as astrophysicist Paul Sutter realized when he began thinking about phenomena he wanted to write about to share his field with readers, high-energy astrophysics is pretty brutal up close. Dying stars, black holes, the vacuum of space, even unknown dangers like hostile aliens — those fascinating-but-brutal scenarios became the beastly specimens catalogued in his new book, "How to Die in Space: A Journey Through Dangerous Astrophysical Phenomena" (Pegasus Books, 2020).

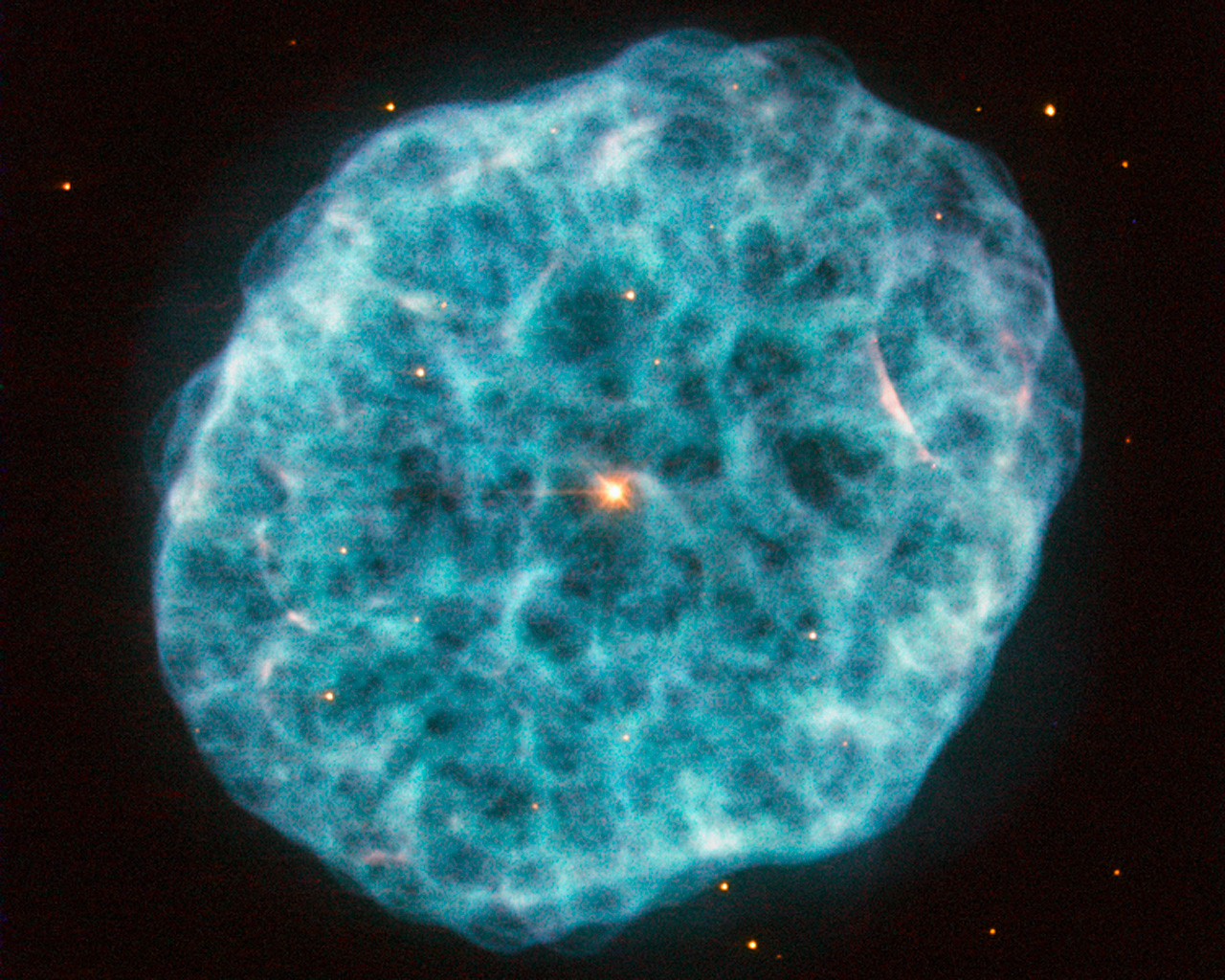

In the excerpt below, Sutter (whose writing you may recognize as a frequent contributor to Space.com) introduces planetary nebulas and explains why, while they're a perennial star of Hubble Space Telescope images, they're best admired from a distance. (Read an interview with Paul Sutter about the book.)

Related: Best space and sci-fi books for 2020

How to Die in Space: A Journey Through Dangerous Astrophysical Phenomena

Pegasus Books, 2020 | $27.95 on Amazon

Join Paul Sutter in a brilliant and breathtakingly vivid tour of the universe, describing the physics of the dangerous, the deadly, and the scary in the cosmos.

Excerpt from Chapter 7: Planetary Nebulas

We've come to an interesting place in our journey through the galaxy.

We've broken out of our home solar system after dodging rogue asteroids, evading circuitry-frying coronal mass ejections from the sun, and simply accepting the flood of tiny cosmic rays constantly bombarding our delicate flesh.

Once we reached interstellar distances, we've seen stars born from clouds of vicious turbulence, and we encountered our first truly exotic creatures of this everlasting night that we call outer space: the black holes.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Those black holes are tombstones.

Markers. Memories of what once was. Almost-forgotten remnants of the past. The black holes of our galaxy used to be stars, shining with heat and light and warmth. Dead, gone now, generations ago. Their fusion finished, their hydrogen depleted, their spirit withered.

The stars of our universe will die, one by one. And those deaths are, to a number, nasty.

Many of the hazards that we're about to explore and explain will come from the variety of ways that stars can end their lives, and turn into other, far less pleasant, things.

Needless to say, it won't be pretty.

And when it comes to stars, everybody wants to go out with a bang. Make a big deal out of it. Sadly, not everybody can shine as brightly, as intensely, as ferociously as a supernova. Don't fret, eager explorer, we'll get to supernovas and other overly powerful explosions soon enough. It's best we start small, with weaker explosions and their consequences, and work out way up to the big leagues. Wouldn't want to get ahead of ourselves.

The Earth's own sun will die someday. Best to accept that fact now, deal with it, internalize it. When the moment comes you don't want to be caught off guard, your eggs half boiled, your grilled cheese sandwich only toasted on one side. We'll use the sun as a textbook lesson, so you won't be caught unawares in an unfamiliar system, so you won't pick a star to call home that will go giant on you in a thousand years.

All stars die. Some, the very largest, go out in a tremendous flash of energy, turning themselves inside out to light up the universe. Others, the smallest, slowly fade, never quite sputtering out, never making a scene, spending a trillion years tending to a weak fire.

The middle ones, like the sun, have the most miserable fates. Before they finally die, they become red and bloated, spewing out their innards through the local system. Spasm after spasm, they slowly lose themselves, leaving only a faint dying heart behind.

It's in these later years when they're most dangerous, when their violence overwhelms them, reducing any hapless inner planets to cinders.

Every year, old stars fade while new ones light up. A continuous cycle in the galaxy. Beautiful and poetic, really, except for the fact that when these stars go they cause mayhem and destruction for anybody unfortunate enough to live within their influence.

You can buy "How to Die in Space" on Amazon or Bookshop.org.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Paul M. Sutter is a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University, host of Ask a Spaceman, and author of How to Die in Space.