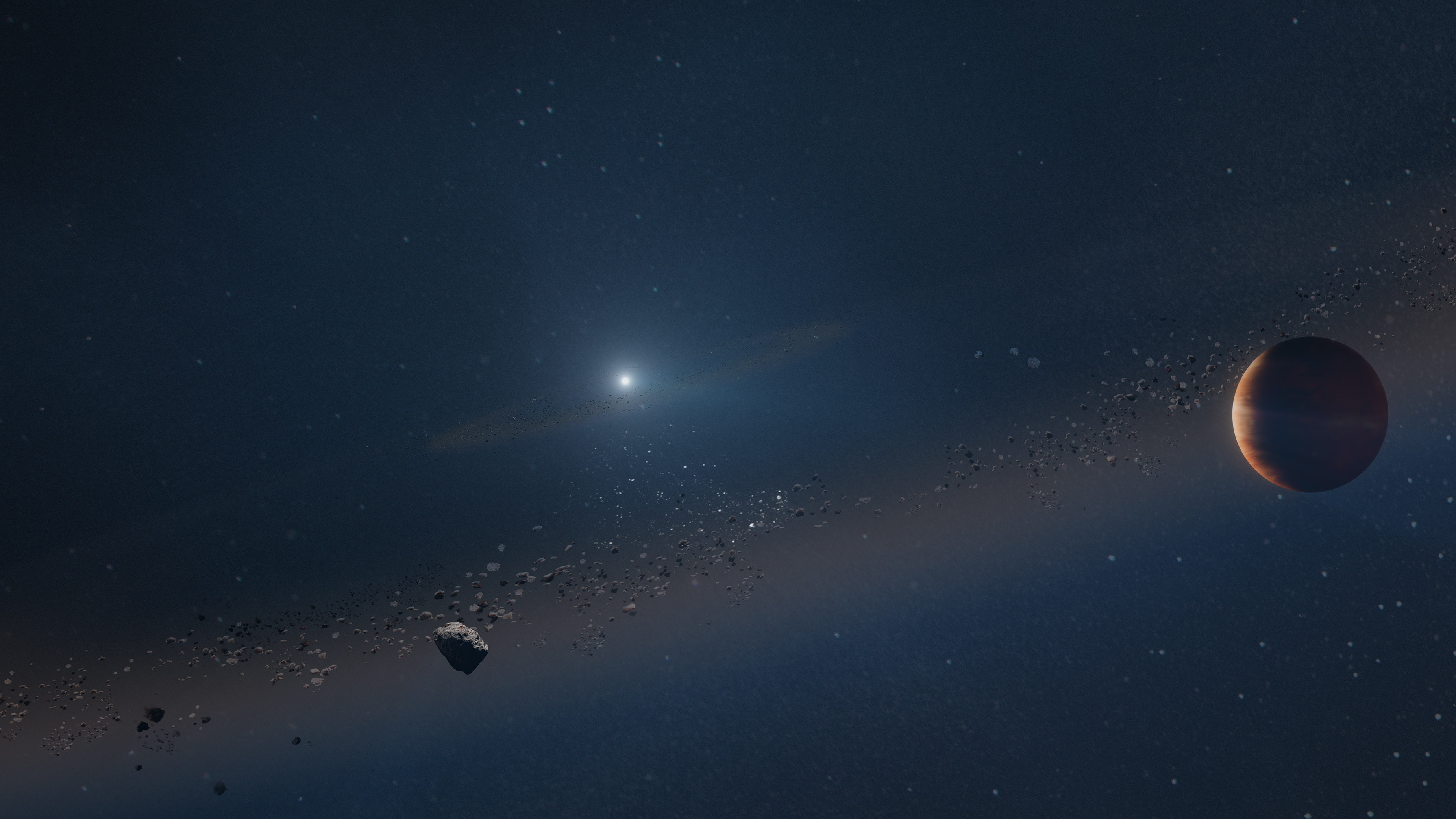

First discovery of planet orbiting dead star provides glimpse into our solar system's future

The first-ever planet discovered orbiting a white dwarf was spotted thanks to gravitational microlensing.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The first-ever discovery of a planet orbiting a dead star suggests that some worlds in our solar system will likely survive the sun's violent death about five billion years from now. But what are Earth's chances?

The newfound planet, a gas giant about 40% larger than Jupiter, and its parent star, which orbits near the center of the Milky Way, were accidentally discovered during a "gravitational microlensing" event in 2010. For a long time, however, astronomers had no clue what they were looking at.

Gravitational microlensing occurs when two stars at different distances from Earth temporarily align from our perspective. The gravity of the star in the foreground acts like a lens and magnifies the light from the background star. If a planet orbits the foreground star, the magnified light briefly warps as the planet whizzes in front of the star.

Article continues below"To detect an object through gravitational microlensing, you are only depending on the mass of the object; you don't need any light coming from it," Jean-Philippe Beaulieu, professor of astrophysics at the University of Tasmania in Australia and director of the Institute of Astrophysics in Paris, told Space.com. "We could see that there was an object about half the mass of the sun with a Jupiter-mass planet orbiting."

Related: Smallest, densest white dwarf ever discovered packs the sun's mass into a moon-size stellar corpse

At that time, the scientists thought it was just another exoplanet, an intriguing but not at all unique finding, added Beaulieu, who is a co-author of a new paper detailing the discovery.

But the astronomers wanted to learn more about the system and decided to study it with one of the W. M. Keck telescopes in Hawaii. To their surprise, they couldn't see anything.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Because [the object] has half the mass of the sun, the Keck telescope, one of the best telescopes of its kind, should be able to detect it," Beaulieu said. "But it didn't find anything."

The scientists concluded that the mysterious body around which the lone planet was orbiting must be either a black hole or a white dwarf, a dim remnant of a star that ran out of fuel in its core and collapsed into a superdense cooling ball about the size of Earth.

"When we looked at the mass range, it was typical of the white dwarf population that we know in our galaxy," said Beaulieu.

The random extrasolar planet discovery suddenly turned into a big deal. No white dwarf had been found before with a planet in its orbit, and scientists had speculated for years whether planets could even exist around white dwarfs.

It's not so much the white dwarf that is the problem for a planet's survival. It's the preceding red giant phase, a stage in the life of most stars that burn hydrogen into helium in their core (the main sequence stars). As the star burns all the hydrogen in its core, its outer layers start collapsing inward, which temporarily increases the temperature inside the core, enabling helium to fuse into carbon. This process generates a powerful outward thrust that expands the original envelope of the star multiple times.

Once the sun reaches the red giant phase, Beaulieu said, Earth will suddenly find itself inside the sun with temperatures of thousands of degrees on its surface.

"There will be nothing left of Earth most likely," Beaulieu said. "But something like Jupiter, which is further out, could survive. Some of its outer layers will be blown out, but it is large enough to persist."

Previously, computer models suggested that this might be the case, but the new discovery finally provides solid proof: some planets can survive their star's red-giant phase.

But what does that mean for humankind? (If we can survive long enough to see the red giant phase of our sun, which is certainly not guaranteed.)

David Bennett, a senior research scientist at the University of Maryland and NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, who is also a co-author of the new paper, said in a statement that humanity's best shot would be to inhabit some of the moons of Jupiter or Saturn. Still, it would not be a "rosy" existence.

"If humankind wanted to move to a moon of Jupiter or Saturn before the sun fried the Earth during its red supergiant phase, we'd still remain in orbit around the sun, although we would not be able to rely on heat from the sun as a white dwarf for very long," Bennett said.

Beaulieu hopes that in the near future, the team might actually be able to see their white dwarf with the help of the Hubble Space Telescope or the upcoming James Webb Telescope, the largest space observatory ever built, which is just being readied for launch at the European spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana.

"We hope that we will be able to not only detect it but to also measure its luminosity and temperature," Beaulieu said. "Once we have that, we would be able to tell the white dwarf's age and that will give us the age of the whole system."

The study was published in the journal Nature on Wednesday, Oct.13.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.