Big, dead European satellite will crash back to Earth this month

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A dead European satellite will come crashing back to Earth later this month, in a fiery death dive that its handlers will monitor carefully.

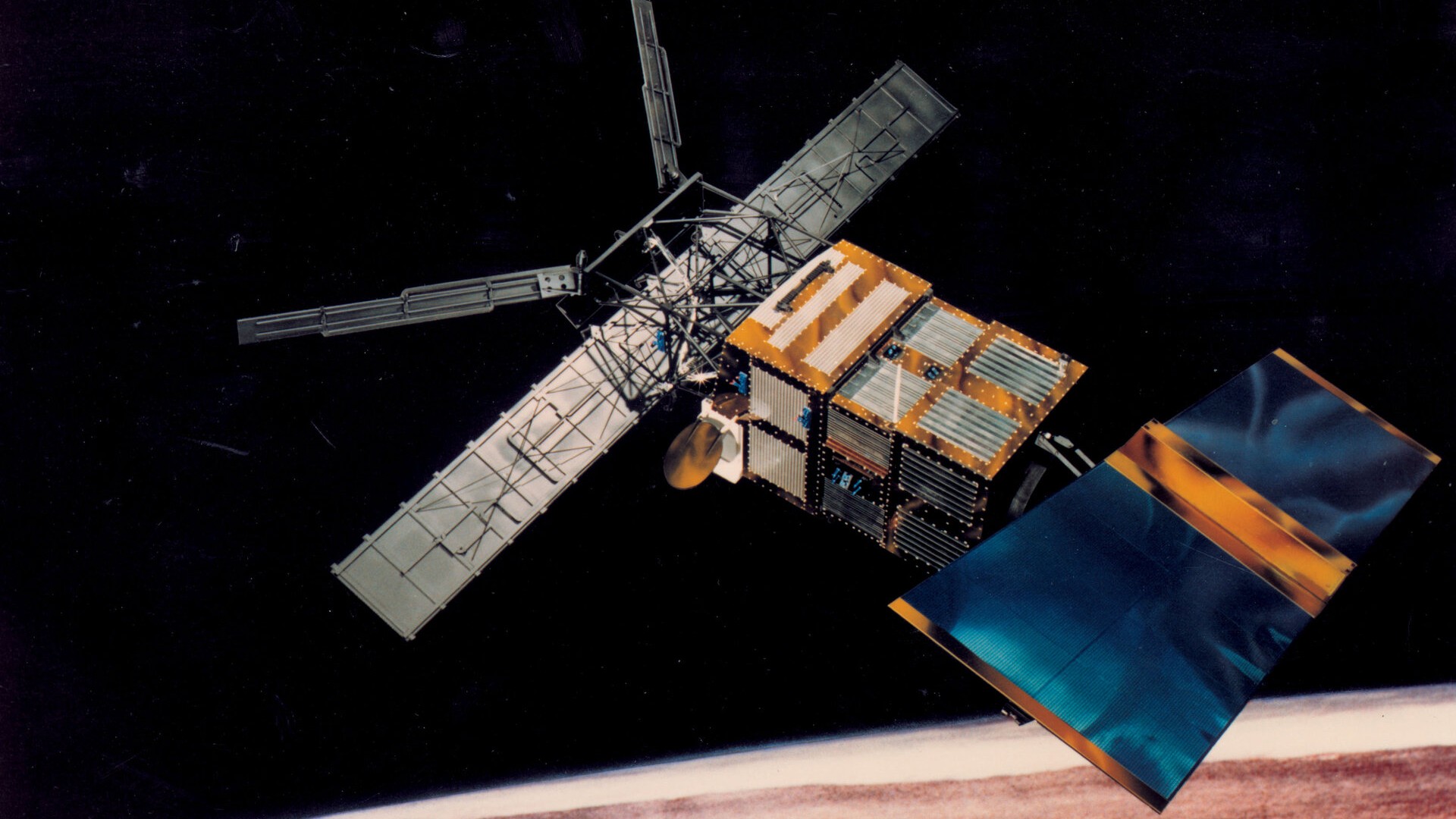

The incoming spacecraft is the European Space Agency's (ESA) European Remote Sensing 2 (ERS-2) satellite, which launched to Earth orbit in April 1995 and wrapped up its Earth-observing duties in September 2011.

ESA began preparing for ERS-2's demise even before its primary mission ended, performing 66 engine burns in July and August of 2011. Those maneuvers "used up the satellite's remaining fuel and lowered its average altitude from 785 km [488 miles] to about 573 km [356 miles] in order to greatly reduce the risk of collision with other satellites or space debris and to ensure the satellite's orbit would decay fast enough for it to reenter Earth's atmosphere within the next 15 years," ESA officials wrote in an FAQ about the coming reentry.

Related: The biggest spacecraft to fall uncontrolled from space

ERS-2 "was the most sophisticated Earth-observation spacecraft ever developed and launched by Europe," according to the FAQ. At the time of liftoff, it weighed 5,547 pounds (2,516 kilograms). Now, without fuel, it tips the scales at about 5,057 pounds (2,294 kg).

That's plenty hefty, but ERS-2 is far from a space junk outlier; objects of similar mass reenter Earth's atmosphere every week or two on average, ESA officials wrote.

And far larger objects have crashed back to Earth recently. For example, the 23-ton core stage of China's Long March 5B rocket comes down uncontrolled about a week or so after each liftoff, a design feature that has drawn the ire of NASA officials and others in the space community.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

These dramatic reentries have occurred three times in the past three years; Long March 5B vehicles lofted the three modules for China's Tiangong space station, in April 2021, July 2022 and October 2022.

ERS-2's fall has been much more protracted, unfolding over the past 13 years. But the satellite is now low enough to be pulled down relatively quickly by atmospheric drag, and the process will only accelerate over the coming days. (This fall is uncontrolled; ERS-2 is out of fuel and therefore can perform no more engine burns.)

It's too soon to predict where and when ERS-2 will hit the bulk of Earth's atmosphere. But chances are good it will reenter over the ocean, as water covers about 70% of our planet's surface.

The satellite will break apart when it hits an altitude of about 50 miles (80 km), according to the FAQ. Most of the resulting fragments will then burn up in the atmosphere. Don't worry too much about the ones the make it down to the surface, for they'll contain no toxic or radioactive substances, according to ESA.

And you'd have to be really, really unlucky to get hit by one of them — or any piece of space junk, for that matter.

"The annual risk of an individual human being injured by space debris is under 1 in 100 billion," ESA officials wrote in the FAQ. That's roughly 65,000 times lower than the risk of being hit by lightning.

ESA will keep us updated about ERS-2's dramatic return to Earth over the coming days. So keep checking back here at Space.com — we'll pass along the important details, including whether or not you may be able to see the satellite's remains streaking through your skies.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.