Dark Matter May Have Existed Before the Big Bang, New Math Suggests

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

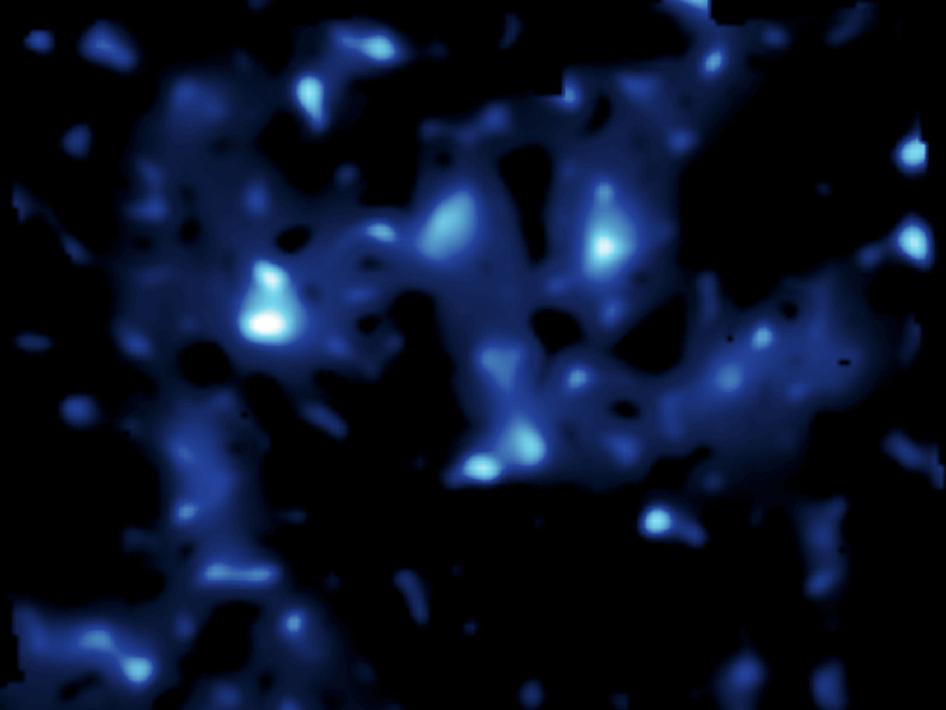

Cracking the mystery of dark matter is one of the most frustrating quests of physics.

One lingering suggestion of how to explain some of the challenges of dark matter is that the strange substance arose before the Big Bang. That moment represents the most popular explanation for how the universe began, in a snapshot singularity that expanded over billions of years into everything that surrounds us. And if dark matter did come first, that changes how scientists should hunt for the substance.

"The study revealed a new connection between particle physics and astronomy," study author Tommi Tenkanen, a physicist at Johns Hopkins University, said in a statement. "If dark matter consists of new particles that were born before the Big Bang, they affect the way galaxies are distributed in the sky in a unique way. This connection may be used to reveal their identity and make conclusions about the times before the Big Bang, too."

Related: Dark Matter & Dark Energy: The Mystery Explained (Infographic)

Tenkanen developed a mathematical model to probe how dark matter interacts with what physicists refer to as scalar particles. In that category, scientists have so far spotted only the Higgs boson. And if dark matter is indeed older than the Big Bang, the substance would definitely have interacted with scalar particles, he said.

"If dark matter were truly a remnant of the Big Bang, then in many cases researchers should have seen a direct signal of dark matter in different particle physics experiments already," Tenkanen said.

The fact that researchers haven't seen such a signal yet is troubling. But Tenkanen said his model may point to a different approach for tackling the dark matter question: focusing on astronomical observations. In particular, he said he sees potential in the European Space Agency's Euclid space telescope, which is scheduled to launch in 2022. That spacecraft is designed to map the edges of the universe, letting scientists look back about 10 billion years.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new research is described in a paper published yesterday (Aug. 7) in the journal Physical Review Letters.

- Eureka! Scientists Photograph a Black Hole for the 1st Time

- 3 Huge Questions the Black Hole Image Didn't Answer

- The Future of Black Hole Photography: What's Next for the Event Horizon Telescope

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.