Europe's veteran gamma-ray space telescope nearly killed by charged particle strike

"We were immensely relieved to get the spacecraft out of this 'near-death' experience," an ESA official said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The European Space Agency (ESA) nearly lost a veteran space telescope last month when a charged particle disabled one of the reaction wheels that keep its solar arrays pointed at the sun.

The incident led to a race against the clock as ground controllers had only three hours of battery time to find a solution before the spacecraft completely lost power, ESA revealed in a statement issued on Monday (Oct. 18)

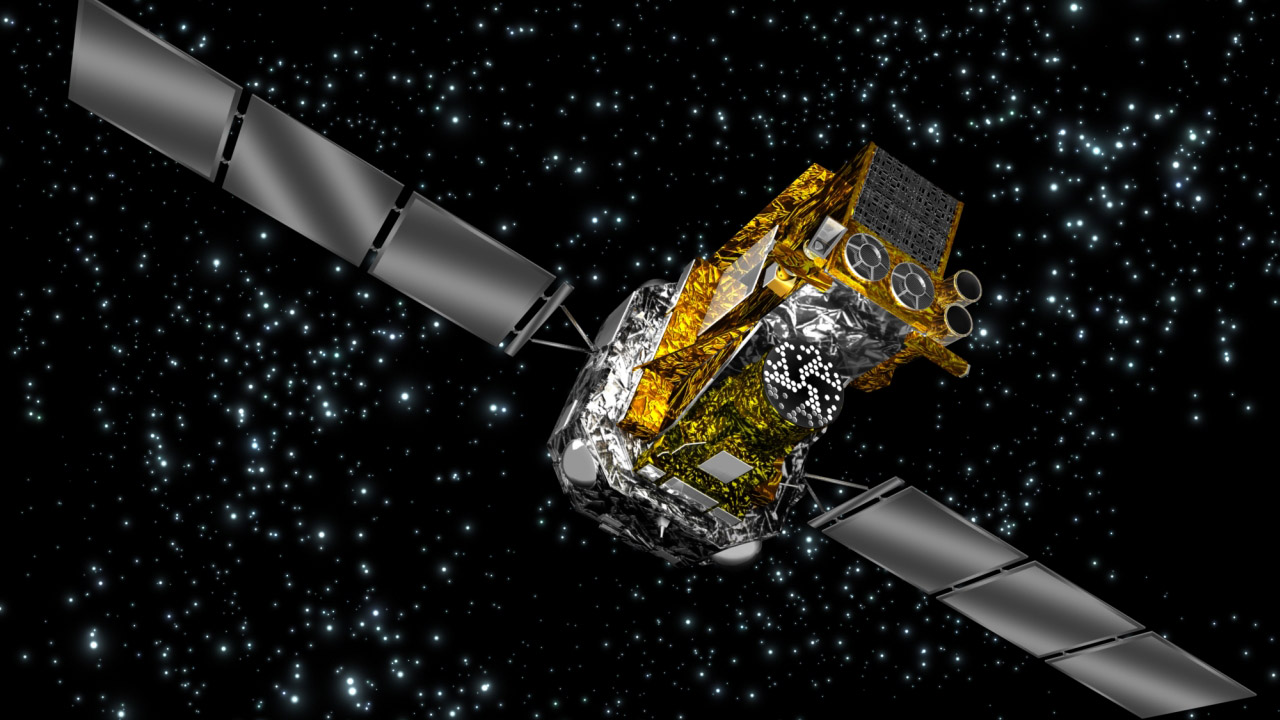

Since 2002, the gamma-ray space telescope Integral has been scouring the sky for sources of high-energy X-rays and gamma rays: the most energetic type of radiation in the universe produced by dense and still little understood objects such as pulsars and neutron stars. But on Sept. 22, ground controllers suddenly realized that something was amiss when patchy data started coming from the 4.4-ton (4 metric tonnes) observatory. Soon after, the spacecraft automatically switched into the so-called safe mode, during which all non-essential systems, including science instruments, shut down.

Article continues below"The data coming down from Integral was choppy, coming in for short periods due to it spinning," Richard Southworth, operations manager of the Integral mission, said in the statement. "This made analysis even harder."

Related: The oldest gamma-ray burst ever discovered was just a piece of space junk

The team soon determined that the choppy data delivery from the spinning spacecraft was due to the loss of one of Integral's three reaction wheels. Reaction wheels control the attitude of a satellite by spinning against the forces that affect the spacecraft in orbit: gravity, atmospheric drag, solar wind pressure and uneven cooling. With one of its three reaction wheels suddenly out of order, Integral started spinning and its solar panels lost illumination.

The 19-year-old Integral, ESA's longest-serving space telescope, has already experienced its share of technical problems, which meant the original back-up systems designed to kick in under such circumstances didn't work.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The batteries were discharging, as there were only short charging periods when the panels briefly faced the sun," Southworth added.

The ground team attempted to reset the affected wheel's function, but the Integral spacecraft kept wobbling and spinning every 21 minutes, five times faster than its operational maximum.

With the spacecraft's battery quickly draining, the operators decided to first switch off additional systems to buy some time to solve the spinning problem. Eventually, the team managed to find a way to reduce the spinning rate by tinkering with the rotation speed of the reaction wheels.

"Everyone breathed a huge sigh of relief," Andreas Rudolph, head of the astronomy missions division at ESA's Mission Operations Department, said in the statement. "This was very close, and we were immensely relieved to get the spacecraft out of this 'near-death' experience."

But what exactly knocked out that reaction wheel? The space agency said the failure was caused by what engineers call a Single Event Upset, which happens when a charged particle strikes a sensitive electrical component. Such incidents are usually caused by the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the sun. Such accidents are frequently caused by solar flares and coronal mass ejections, powerful bursts of magnetized plasma from the sun's upper atmosphere, the corona.

Strangely, this incident happened while the sun was rather quiet.

"This strike happened on a day when no relevant space weather activity was observed," Juha-Pekka Luntama, ESA's head of space weather, said in the statement. "Based on a discussion with our colleagues in the flight control team, it looks like that the anomaly was triggered by charged particles trapped in the radiation belts around Earth."

The Van Allen radiation belts are two donut-shaped regions around our planet where charged particles from the solar wind get trapped inside Earth's magnetic field. Extending between altitudes of 400 to 36,000 miles (640 to 58,000 kilometers), the radiation belts are a known threat to satellites in orbit because of their high levels of charged particles.

In the days following the original emergency, Integral spacecraft controllers had to repeat the stabilizing procedure as the observatory again started to spin.

ESA said in the statement the secondary problem may have been caused by a star tracker that was temporarily blinded by Earth. Star trackers are cameras that help a satellite maintain its position by monitoring the position of stars.

The spacecraft has been stable since Sept. 27 and all systems were turned on again on Oct. 1, ESA said in the statement. The spacecraft is now in the middle of an observation campaign focusing on massive stars in the constellation of Orion.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.