Ancient clam fossil reveals Earth's day was shorter 70 million years ago

A 24-hour day seems so natural here on Earth, but 70 million years ago, that would have felt leisurely to creatures accustomed to making do with just 23.5.

Thanks to the fossilized remains of one of those creatures, scientists have been able to pinpoint that time difference, and in turn, the celestial migration that it has caused. A team of scientists has published a description of the fossil and the evidence they found in it: When the dinosaurs reigned, Earth's year lasted 372 slightly shorter days.

"We have about four to five data points per day, and this is something that you almost never get in geological history," Niels de Winter, a geochemist at Vrije Universiteit Brussel and the lead author of the new study, said in a statement released by the study's publisher. "We can basically look at a day 70 million years ago. It's pretty amazing."

Related: How the moon evolved: A photo timeline

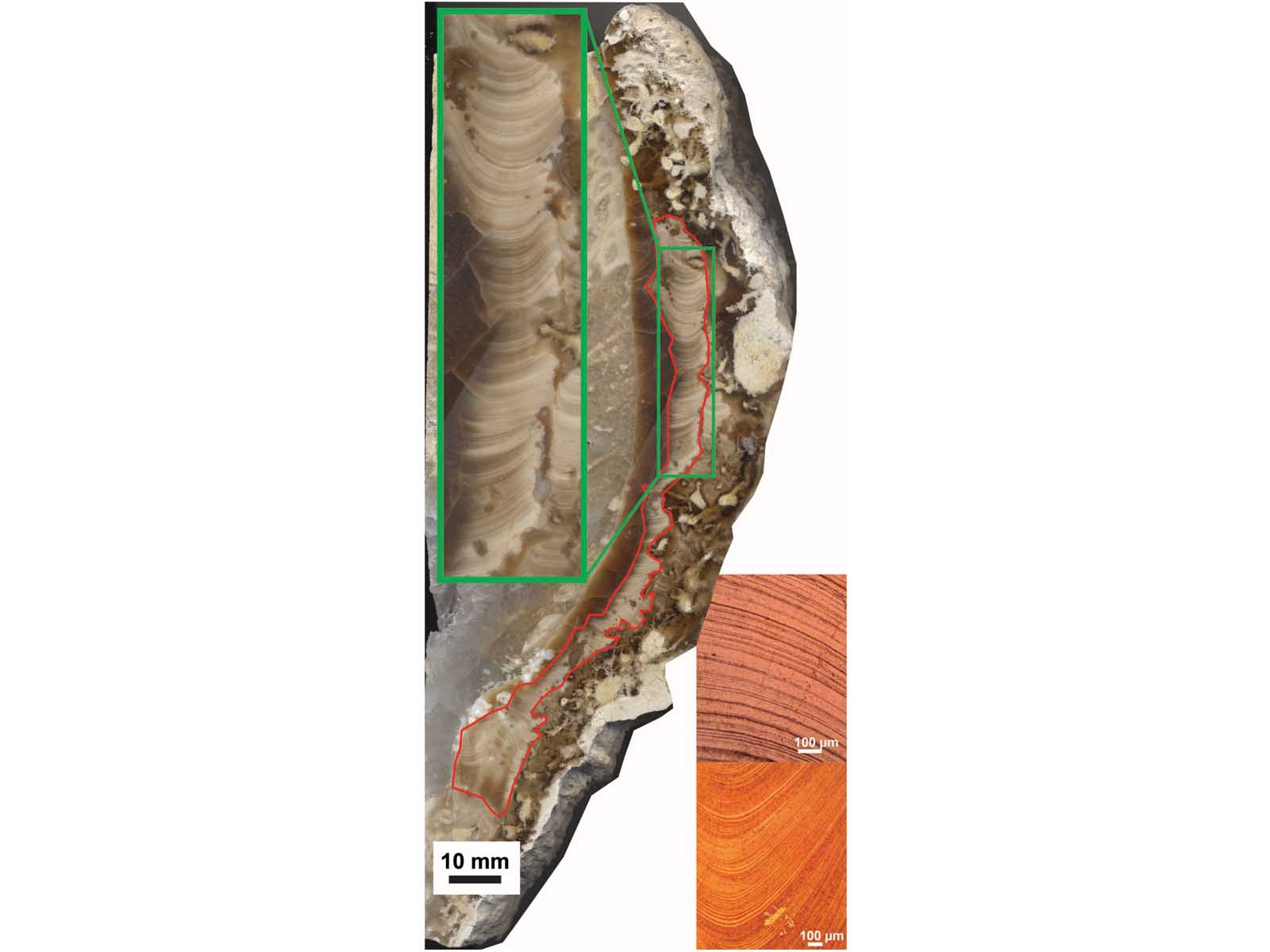

The fossil that gave de Winter and his colleagues so many data points is the shell of an extinct type of clam. The researchers extracted a superthin core from the fossil, which can offer a sense of the conditions an animal lived in. And, like tree rings, the shell also offered the scientists an understanding of the rhythms that shaped the clam's life.

But in addition to seasonal changes, the shell also showed growth differences on a tiny scale, marking the difference between day, when the shell grew more, and night. That suggests clams of this type shared their shells with bacteria that, like plants, could turn sunlight into sugars.

And when the researchers counted those daily layers, they realized that for each year — which has remained uniform over the eons, they knew — the clam had seen 372 days. To make the math work with an extra 6.75 spins per year, a day must have been 23.5 hours long.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You don't need to get excited about the daily routines of long-extinct clams to find the new research intriguing, however. That's because the rate at which Earth spins is tied to the distance between Earth and the moon: As Earth slows down, the moon drifts a tiny bit farther away.

Scientists already knew that Earth has been slowing and the moon has been drifting away. Retroreflector instruments placed on the moon during the Apollo missions have allowed scientists to measure the rate of that drift today: about 1.5 inches (3.8 centimeters) per year.

But that rate can't be steady across geologic history. If it were, Earth and the moon would have been occupying the same space about 1.4 billion years ago — which is pretty awkward, given that scientists know the moon formed more like 4.5 billion years ago. So the drift must have been slower in the past.

The fossil shell represents a first step toward pinning down the timeline of how Earth's spin slowed and the moon drifted away. This lone clam won't be enough, particularly since it is so young in the context of the moon's age, but the scientists hope to be able to conduct similar analyses with other, older fossils that would round out the timeline.

The research is described in a paper published Feb. 5 in the journal Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology.

- See the Earth and moon from 40 million miles away (photo)

- See the 2020 Super Worm Moon over NYC and Washington, D.C. in these awesome photos

- Surprise! Earth and the moon aren't made of exactly the same stuff.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.