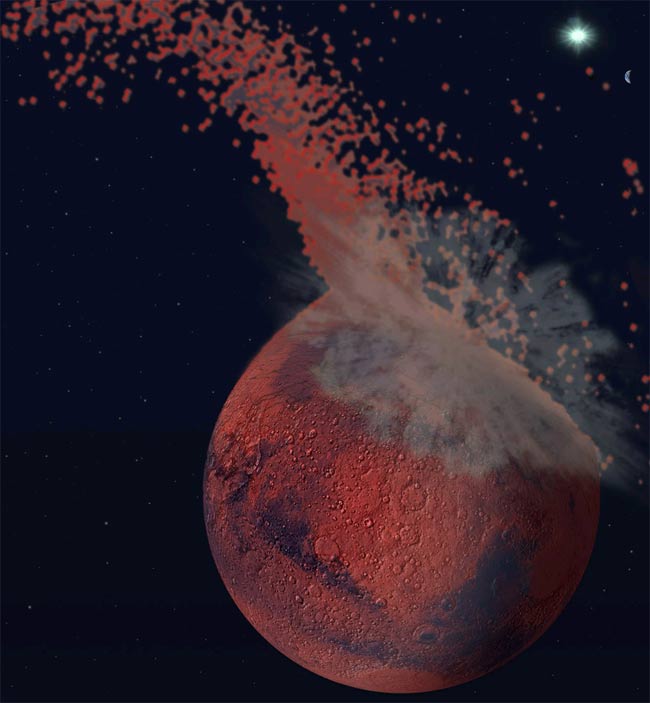

Huge Impact Created Mars' Split Personality

Mars' two-faced nature may have been caused by a giant kickin the head, according to a new study.

Recent evidence suggests the vast disparity seen between thenorthern and southern halves of the planet is caused by the long ago impact ofa gigantic space rock into Mars.

The finding, based on a survey of the red planet's gravityand topography, provides the first convincing support for the idea that the redplanet is the site of the largest impact crater in our solar system. Thecollision that caused the scar would have occurred more than 3.9 billion yearsago, the researchers said, around the time an even larger asteroid is thoughtto have struck Earth, formingour planet's moon.

"This impact is really one of the defining events inMars' history," said MIT postdoctoral researcher Jeffrey Andrews-Hanna,who led the new study with MIT geophysicist Maria Zuber and NASA Jet PropulsionLaboratory researcher Bruce Banerdt. "More than anything this hasdetermined the shape of the planet's surface. Mars would not be the planet itis today if this hadn?t occurred."

Two-faced planet

Scientists have been scratching their heads trying toexplain the differences between the two sides of Mars for about 30 years. Thenorthern hemisphere of the planet is smooth and low, and some experts think itmay have contained avast ocean long ago. Meanwhile, the southern half of the Martian surface isrough and heavily-cratered, and about 2.5 miles to 5 miles (4 km to 8 km)higher in elevation than the northern basin.

Scientists first proposed the idea of a space rock impact toexplain the difference in 1984, but for a long time this hypothesis had less supportin the field than a competing idea, that internal processes, such as theconvection of heat through the mantle, created the different features.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"In the past it has been thought that it just doesn'tlook like an impact crater," Andrews-Hanna said. "The outline justlooked irregular, not circular."

By combining detailed topographical data from the MarsGlobal Surveyor mission with measurements of the variations in the planet'sgravitational field made by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter satellite,Andrews-Hanna and his team assembled a map of the Martian surface beforevolcanic eruptions added layers and obscured the boundary between thehemispheres. The map revealed a stunning elliptical basin shape covering about40 percent of Mars' surface.

"This was a kind of surprising result," Andrews-Hannasaid. "What we noticed is that the dichotomy boundary around the planetwas actually smooth and regular. We tested to see if we could fit this with anyshape, and it just so happens that it's almost perfectly fitted by an ellipse.There's only one process that?s known to make an elliptical depression likethat, and that?s a giant impact."

The discovery helps to overcome a major criticism of the spacerock impact suggestion, that there is not enough visual evidence to support it.

"This is the one thing that nobody had seenbefore," Andrews-Hanna told SPACE.com. "One of the mainarguments against the giant impact hypothesis was that it doesn?t look like animpact basin, therefore that's not a good solution. Now we can say that all theevidence we have available to us is pointing toward a giant impact. We can'tdisprove the other hypotheses, but I think it becomes a challenge now for thosehypotheses to explain the feature."

The elliptical crater the study revealed is roughly 5,300miles (8,500 km) across and 6,600 miles (10,600 km) long, about the size of thecombined area of Asia, Europe and Australia. That makes this crater about fourtimes larger than the next-biggest impact basins known, the Hellas basin onMars and the South Pole-Aitken basin on the moon.

Proof?

The research changes the debate about the two faces of Mars,but doesn't settle the question forever.

"I think it's an important step forward, but it's notthe last word," said Jay Melosh, a planetary scientist at the Lunar andPlanetary Lab at the University of Arizona, who was not involved in the newstudy. "It certainly makes the impact scenario look a lot more plausiblethan it did before. It?s a very strong argument in favor of the giant impact,but there is still no proof."

In order to prove the features seen on Mars are the resultof a space rock smash and not some other event or process, scientists wouldneed to find rocks or minerals that could have formed only as the result of animpact.

"If you have a big impact it changes the rocks incharacteristic ways," Melosh said. "Minerals like quartz are changedinto a form that only occurs at high pressure. It's thatkind of change we use on Earth to verify whether impact craters are causedby an impact or something else. If they are right we should be able to findevidence in Martian rocks."

This kind of test will have to wait a while until humans canmount missions to Mars to search for these rocks. Scientists would probablyneed a suite of samples returned from various areas on the planet to be sure,Melosh said.

Modeling the impact

The map created by Andrews-Hanna and his colleagues will be publishedin the June 26 issue of the journal Nature, along with two other papersthat support the Mars findings.

For the latter papers, two groups of researchers usedcomputer models to study the effects such an impact would have had on theplanet.

Caltech graduate student Margarita Marinova and planetaryscientists Oded Aharonson of Caltech and Erik Asphaug of the University ofCalifornia, Santa Cruz (UCSC) tested a series of theoretical space rocksapproaching Mars with various velocities, energies and sizes. The scientistsfound that an asteroid about one-half to two-thirds the size of Earth's moonstriking Mars at an angle of 30 to 60 degrees could have produced a basin suchas the one mapped by Andrews-Hanna's team.

The results help address one of the other main objections tothe impact hypothesis ? the suggestion that any space rock massive enough toform such a large basin would have melted so much of the planet's surface thatall evidence of it would be erased.

"They found, contrary to what was previously thought,that you don?t produce that much melt," Andrews-Hanna said. "Most ofthe melt gets contained in the basin."

Another computer model, by UCSC planetary scientist FrancisNimmo, graduate student Shawn Hart, associate researcher Don Korycansky, andCraig Agnor of Queen Mary University, London, complements these findings.

This group simulated the behavior of the Martian crustduring an impact and found that not only could an impact such as the oneproposed cause the differences seen in Mars' two halves, it could also explainother features seen on the red planet, such as magnetic field anomalies foundin the Southern hemisphere.?

Nimmo's model showed how shock waves from the impact on the northernhemisphere would travel through the planet and disrupt the crust on the otherside, causing changes in the magnetic field.

"The impact would have to be big enough to blast thecrust off half of the planet, but not so big that it melts everything,"Nimmo said. "We showed that you really can form the dichotomy thatway."

- Video: Fly Over the Two Faces of Mars

- Video: Mars Mysteries

- The 10 Best Mars Images Ever

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.