Tackling Moondust for Future Lunar Living

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

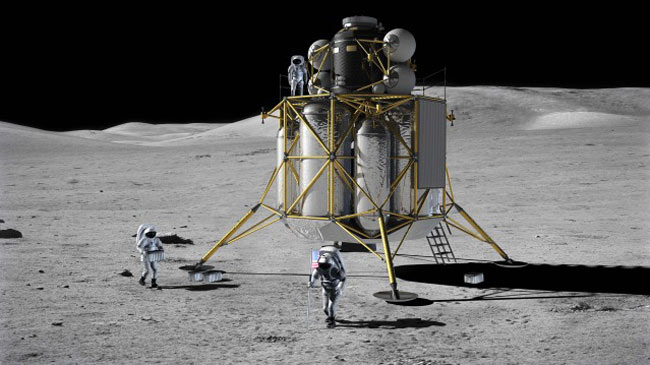

Better living on the moon could start with keeping lunardust out.

Astronauts living on a permanent moon base will need protection against thebleak world?s asbestos-like dust, not to mention shielding from radiation and aplan to ward off psychological demons.

Those challenges weigh on NASA's plans to send humans back to the moon beforethe end of the next decade, when four-astronaut crews would have to learn howto live on the lunar surface in a space the size of a small mobile home.

"It's not just like dirt in your house," saidRobert Howard, engineer and manager of NASA's Habitability Design Center, ofthe moon?s ubiquitous dust.

Lunar dust began as a problem back when Apollo astronauts found the gray powderclinging to everything. Even the vacuumdesigned to clean the spacesuits and spacecraft choked on the stuff.

Now researchers want to know how much dust would settle in astronaut lungswithin the moon's reduced gravity of just one sixth that of Earth's gravity.

"In the big picture, the questions are: How much goes into the lung? Wheredoes it go? How long does it stay? And how nasty is the stuff?" said KimPrisk, a medical researcher at the University of California, San Diego.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronauts may spend up to six months living with thelunar dust that resembles fresh-fractured quartz, a highly toxic substance.Reduced gravity could keep dust particles suspended in the airways, whichprovides more time for the toxic dust to get deep into the lungs and reach thebloodstream.

Prisk and other researchers of the National Space Biomedical Research Institutemonitored volunteers who breathed in dust-sized particles during flights onNASA's Microgravity Research Aircraft. The airplanes can make steep dives tobriefly simulate reduced- and zero-gravity.

"With the reduced-gravity flights, we?re improving the process ofassessing environmental exposure to inhaled particles,? Kim said. ?We?velearned that tiny particles (less than 2.5 microns or 0.0025 millimeters) whichare the most significant in terms of damage, are greatly affected byalterations in gravity."

Howard and other NASA engineers already have ideas on how to clear out unwanteddust in lunar habitats. Electromagnets could pull or drive off lunar dust thathas metallic qualities, while air hoses could also help.

Astronauts might even leave their suit outside after attaching to a suit portoutside the moon base or a lunar rover.

"The suit never comes into the vehicle," Howard told SPACE.com,adding that astronauts could crawl out of the suit and into the vehicle afterlocking into place.

That would also require a new lunar rover that's moremini-RV rather than dune buggy, Howard said.

Radiation and recreation

Another hazard to astronaut health would come fromdangerously high levels of space radiation. Massive solar storms or galacticcosmic rays from far off could have fatal consequences for any living being onthe moon. By contrast, astronauts living on the International Space Station andflying on shuttle missions are protected from the worst by Earth's magneticfield.

Previous ideas for radiation countermeasures include using electrostatic shielding to protect lunarinhabitants. Howard noted that ridges near the moon's South Pole could ideallyhouse an underground base. Astronauts could also tote around portable shieldinginside the habitats in cases of emergency involving "short duration, highradiation" events.

Howard and other engineers have not forgotten the human component to living onanother world, despite grappling with the technical challenges.

"I'm a habitability person, so I'm focused on the psychologicalwell-being," Howard said.

He pointed to psychological lessons from living on thespace station and observed the importance of having "a place to call yourown" as private quarters.

Learning to live on the moon would ultimately provide a stepping stone towardslearning to live in other alien environments. Call it a dry run for the even more daunting and distant prospect ofliving on Mars.

"It's just five days away in an emergency, so we can go home if we haveto," Howard said. "We have to have it right before going toMars."

- Video: Robo-Athlete for the Moon

- Video: Moon meets Rover

- Video: Moon 2.0: Join the Revolution

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.