NASA's New Horizons Just Made the Most Distant Flyby in Space History. So, What's Next?

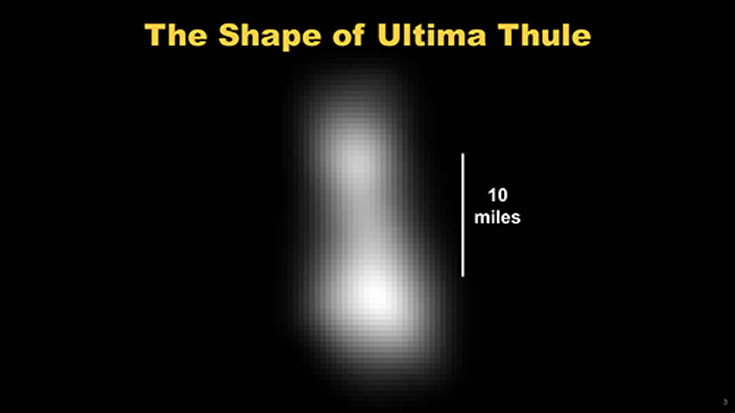

LAUREL, Md. — NASA's New Horizons spacecraft has completed its epic flyby of the most distant object ever explored, the recently-unveiled fossil from the beginning of the solar system, Ultima Thule. So what's next?

Although the Jan. 1 encounter is over, the mission is far from finished. New Horizons still has images of Ultima Thule to send back, more of the Kuiper Belt to study, and the hope of one day leaving the solar system completely.

With the spacecraft safely past its target, a primary concern is its condition. After all, it can't send home data if it isn't functioning. Fortunately, health doesn't currently appear to be an issue. [New Horizons at Ultima Thule: Full Coverage]

"Everything looks great," Mission Operation Manager Alice Bowman told the press after the flyby.

"We're definitely looking forward to getting down the science data so all of our scientists—and the world — can see what the origins of our solar system has to hold for us."

An extensive process

During its fleeting pass over Ultima Thule, New Horizons filled its hard drive with about 7 gigabytes of data about the tiny Kuiper Belt Object (KBO). With the observations complete, it must begin the arduous task of sending that data back home. [Ultima Thule in Photos: Images from the Kuiper Belt]

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But before New Horizons can dig into the process, the spacecraft will be temporarily silenced by the sun. For a few brief days, from Jan. 4 to 9, the sun's atmosphere will block transmissions from New Horizons back to Earth. During that time, the science team will disperse, returning to their homes for a few days of downtime.

As soon as spacecraft clears the sun, the researchers will return to consuming each day's new data, working remotely in several small teams and meeting back together again at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL) in Maryland on Jan. 15.

They won't be hanging around Maryland the whole time, however. At about 1,000 bits per second, it will take roughly 20 months to send home all of the newly-collected data about Ultima Thule. Eventually, they'll head home again, meeting remotely and occasionally in person to discuss their discoveries.

The arrival of the images and information is highly prioritized, according to principle investigator Alan Stern, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Colorado.

"Even though the spacecraft has performed perfectly now for almost 13 years, there's always the chance that something could go amiss," Stern told the press after the flyby.

Information about the highest priority objectives, such as the geology and composition, as well as the potential for rings or moons, will be beamed home first. Secondary goals pertaining to dust escape, craters, and physical surface properties will take second string.

Only once that information has been sent back will the lowest-priority and bonus objectives related to more detailed properties of any rings and moons, information about the mass and density, and extra compositional studies return to Earth.

The first few downlinks will contain a little bit of everything.

"We want to get data sets from each of the instruments on the ground," Bowman said.

According to Bowman, although Ultima Thule is much smaller, New Horizons is collecting roughly the same amount of data as it retrieved at Pluto. But Ultima Thule is more than a billion miles farther from Earth than Pluto, so it takes even longer for the information to travel home.

All of it is relayed by a 15-watt radio transmitter whose weak signal is directed at Earth.

"I am in awe that we can even do this," Stern said about the communication process.

Extending the mission

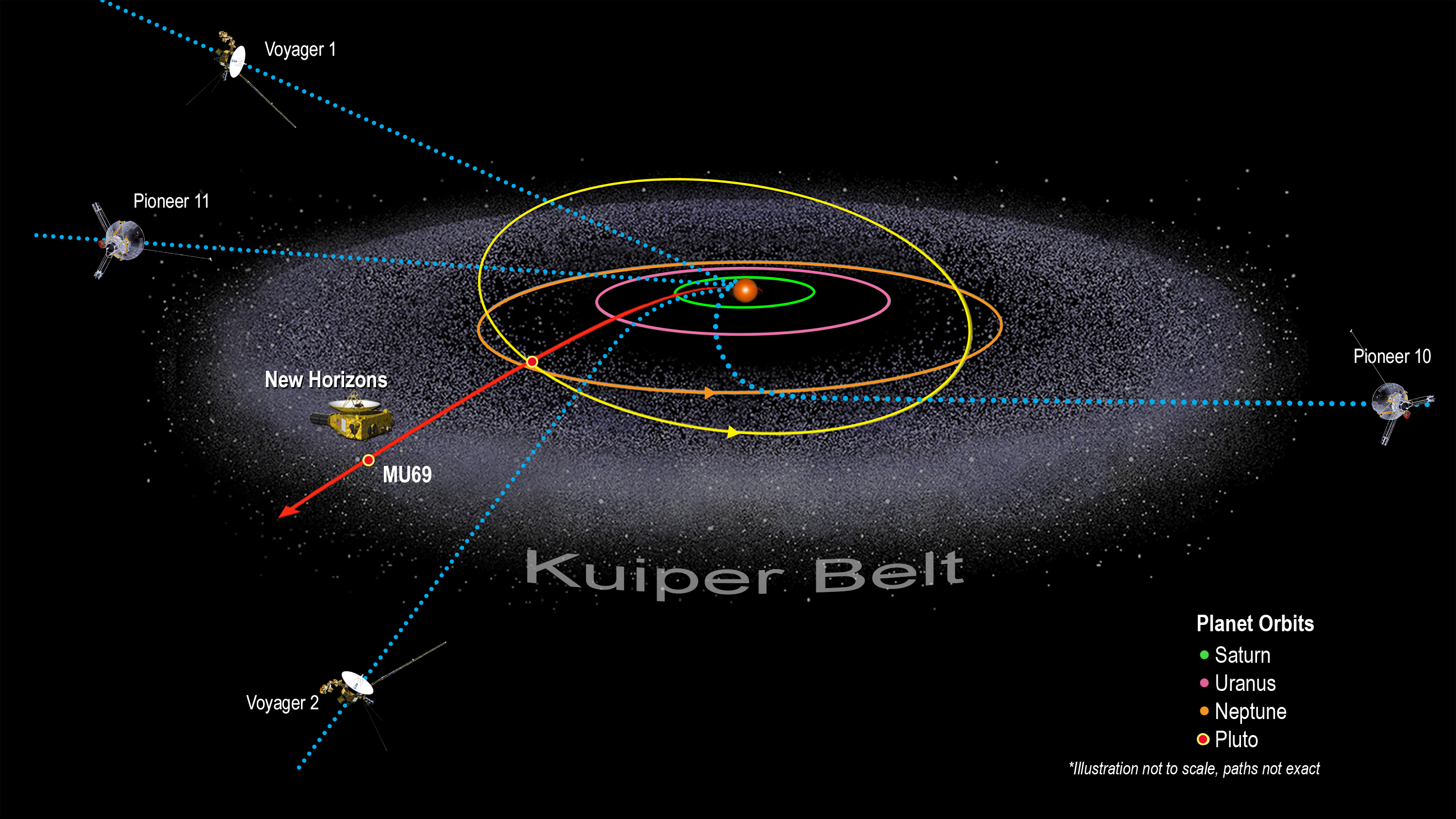

After buzzing Pluto in 2015, New Horizons began an extended mission, the highlight being the Ultima Thule flyby. But that's not the only goal of the spacecraft's next phase. It will continue to study the Kuiper Belt, the band of ice and rocks that makes up the third zone of the solar system, until at least April 2021 when its current mission funding ends.

The team is already looking towards a hyperextended mission.

"We expect to have plenty of fuel left when we finish Ultima Thule," Project Scientist Hal Weaver said before the flyby. "We'd like to try to find another KBO along the way."

The Kuiper Belt stretches from about 30 to about 55 astronomical units (AU), and Ultima Thule is smack in the middle of it. [An AU is the distance between Earth and the sun]. According to Stern, New Horizons will be in the Kuiper Belt until 2027 or 2028.

"It would be silly not to look for another target," Stern said.

The hunt might prove to be more difficult than originally anticipated. While New Horizons was on its way to Pluto, the researchers spent years combing the sky with NASA's Hubble Space Telescope before finally finding three potential targets, finally selecting Ultima Thule because it was the closest. The lonely object lies in the most heavily populated region of the Kuiper Belt.

According to Weaver, Ultima Thule is the faintest KBO ever observed, in part because it lies so far away. The next target will orbit even farther out, making it potentially even fainter and harder to see from Earth.

The best telescope for discovering the next target might be New Horizons itself. Weaver said that it might be possible to modify the flight software so that the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), the spacecraft's camera, could be used as a discovery device for finding KBOs along New Horizons' path.

LORRI could take hundreds or even thousands of photographs of the stars around the spacecraft. Rather than send those images back to Earth, it might be possible to program the computer to search for the best targets and only send home those images. Weaver said that such plans are still on the drawing board.

But the team won't immediately begin stressing about their next mission. According to Stern, they won't submit a proposal for the next extended mission until the summer of 2020. In the meantime, they will hunt for New Horizons next target.

"I'm relatively optimistic," Stern said.

Say goodbye

When New Horizons flew past Ultima Thule, it zoomed by at 32,000 mph (14 km/s). With these speeds, the spacecraft will be able to break free from the sun's gravitational pull and travel beyond the solar system, like NASA's Voyager and Pioneer spacecraft.

When that will happen remains a mystery. The boundary between the heliosphere, the region that surrounds the sun, and the interstellar medium (ISM), the region between the stars, changes with the 11-year solar cycle. That makes it difficult to predict where it will be in 20 years, Stern told Space.com in the weeks before the flyby.

New Horizons should hold onto power until around the late 2030s, Stern said, when it will be just past 100 AUs from the sun. The boundary could be anywhere from 70 to 130 AUs in the most extreme cases.

"No model can predict whether we can see interstellar space before we run out of power," Stern said. But he thinks there's a good chance that the spacecraft will still have power when it crosses the ever-changing boundary.

That would be an excellent thing for science. Although both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 have instruments that have been measuring ISM particles, Stern said that New Horizon carries not one but two more powerful instruments. With these instruments, the spacecraft could make more accurate measurements than its predecessors.

In addition, New Horizons has the Student Dust Counter, which currently holds the record for the most distant working dust detector in space.

"Putting a dust detector in the ISM would be a very valuable experience," Stern said.

New Horizons will leave the solar system whether it targets another KBO or remains on its present course, he said.

Whether New Horizons extends its mission or continues straight on from Ultima Thule, its scientists are excited to see the new images the spacecraft will be delivering down the road.

"It just keeps getting better and better," Weaver said.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky