Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Another red dwarf has been caught firing off a superpowerful flare, further bolstering the notion that life might have a hard time taking root around these small, dim stars.

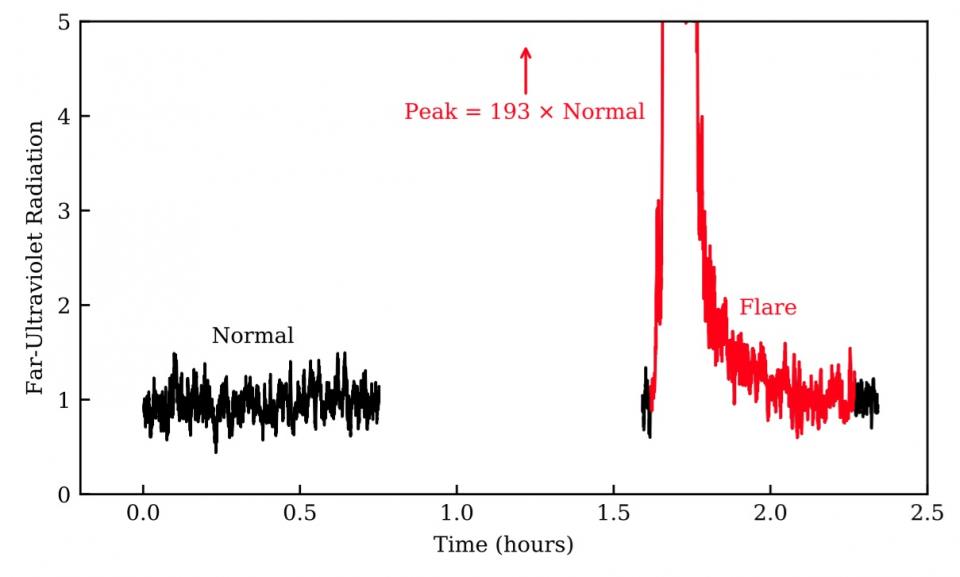

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope spied the superflare coming from a red dwarf called J02365, which lies about 130 light-years from Earth, a new study reports. The outburst featured about 10^32 ergs of energy in the far-ultraviolet realm of the electromagnetic spectrum, making it more powerful than any of our own sun's recorded flares, study team members said.

"When I realized the sheer amount of light the superflare emitted, I sat looking at my computer screen for quite some time just thinking, 'Whoa,'" study lead author Parke Loyd, a postdoctoral researcher in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University, said in a statement. [The Sun's Wrath: Worst Solar Storms in History]

Loyd and his colleagues dubbed this monster the "Hazflare," after the name of the Hubble observing program that detected it. That program is HAZMAT, short for "Habitable Zones and M Dwarf Activity across Time."

HAZMAT is surveying red dwarfs, which are also known as M dwarfs, of three different ages: young (about 40 million years old), medium (about 650 million years) and old (several billion years). The goal is to better understand the habitability of the planets that circle red dwarfs.

This is a key question for astrobiologists, because red dwarfs host the most real estate in the galaxy. About 75 percent of the Milky Way's stars are M dwarfs, and many of them likely have planets in the "habitable zone" — the range of distances from a star that can support the existence of liquid water, and therefore life as we know it. In fact, the nearest star to the sun, the red dwarf Proxima Centauri, has a planet called Proxima b that appears to orbit in the habitable zone.

In addition, red dwarfs burn for trillions of years, offering life a very long window to get going and to diversify. (Sunlike stars, by contrast, live for just 10 billion years or so.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The habitable zone is a controversial topic. Some researchers question the utility of focusing on liquid surface water, given that our own solar system contains multiple worlds with potentially habitable buried oceans — for example, the Jupiter moon Europa and the Saturn satellite Enceladus.

And other scientists criticize the idea as too simplistic given the many variables involved in habitability. For instance, the classical definition doesn't account for planetary mass, which can have a big impact on the reach and range of the habitable zone. Heftier worlds retain their internal heat longer and can also hold onto thicker atmospheres, which could contain more heat-trapping greenhouse gases.

And things get even more complicated with red dwarfs. Because these stars are so dim, their habitable zones lie very close in — so close, in fact, that habitable-zone planets like Proxima b are probably tidally locked, always showing the same face to their star just as the moon always shows its near side to Earth.

A world with a scorching-hot dayside and a bone-chilling nightside might not be a very life-friendly place. Some research suggests that a habitable-zone red-dwarf planet can avoid this fate if it retains an atmosphere thick enough to transport and diffuse the dayside heat. But then we run into another complication — flares. Especially incredibly powerful ones like the Hazflare.

Red dwarfs are very active in their youth, emitting lots of such flares. Astronomers have documented this activity repeatedly; for example, Proxima Centauri was seen to fire off a superflare in March 2016. Such flares may strip away the atmospheres of habitable-zone planets like Proxima b in short order, making such worlds very unlikely abodes for life, some scientists say. [Proxima b: Closest Earth-Like Planet Discovery in Pictures]

But that’s just conjecture at this point, said HAZMAT principal investigator Evgenya Shkolnik, an assistant professor in ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration.

"I don't think we know for sure one way or another about whether planets orbiting red dwarfs are habitable just yet, but I think time will tell," Shkolnik said in the same statement. "It's great that we're living in a time when we have the technology to actually answer these kinds of questions, rather than just philosophize about them."

The new study reports the results of HAZMAT's first phase — observations of the flaring frequency of 12 40-million-year-old red dwarfs. The data suggest that flares from the youngest red dwarfs are 100 to 1,000 times more potent than flares emitted by older M dwarfs, the researchers said.

Future HAZMAT observations will further clarify the relationship between age and flaring. The program will next study middle-aged red dwarfs, and then turn its attention to the elders.

The new paper has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal. You can read it for free at the online preprint site arXiv.org.

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There," will be published on Nov. 13 by Grand Central Publishing. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom or Facebook. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.