To Find Alien Life, NASA Needs Bigger, Bolder Exoplanet-Hunting Telescopes

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A congressionally mandated report published today (Sept. 5) by the premier science advisory group in the United States has found that NASA should focus its exoplanet research budget on large space- and ground-based telescopes.

The new National Academy of Sciences report feeds into a decadal priority-setting system in the astronomy community that guides NASA's long-term strategy.

"The really big message is that this is a very special moment in human history," David Charbonneau, an astronomer at Harvard University and co-chairman of the committee behind the new report, told Space.com. "Humans have wondered about whether there's life on other planets for hundreds of years, arguably thousands of years." [13 Ways to Search for Intelligent Aliens]

If we choose to make the right investments, he continued, "We actually could learn the answer to that question in the next 20 years."

And according to the new report, those investments are clear, with seven key priorities called out, including building a space telescope powerful enough to directly see exoplanets; building large, ground-based telescopes; and continuing the development and launch process for the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST) space-based telescope.

"In this report, they really double down on the big mission strategy," Jessie Christiansen, who studies exoplanets at Caltech and NASA's Exoplanet Science Institute and wasn't involved in the new report, told Space.com. "These will be incredibly large, expensive efforts, but they could achieve something we're excited about," she said — like finding and studying small, rocky planets around stars like our own sun.

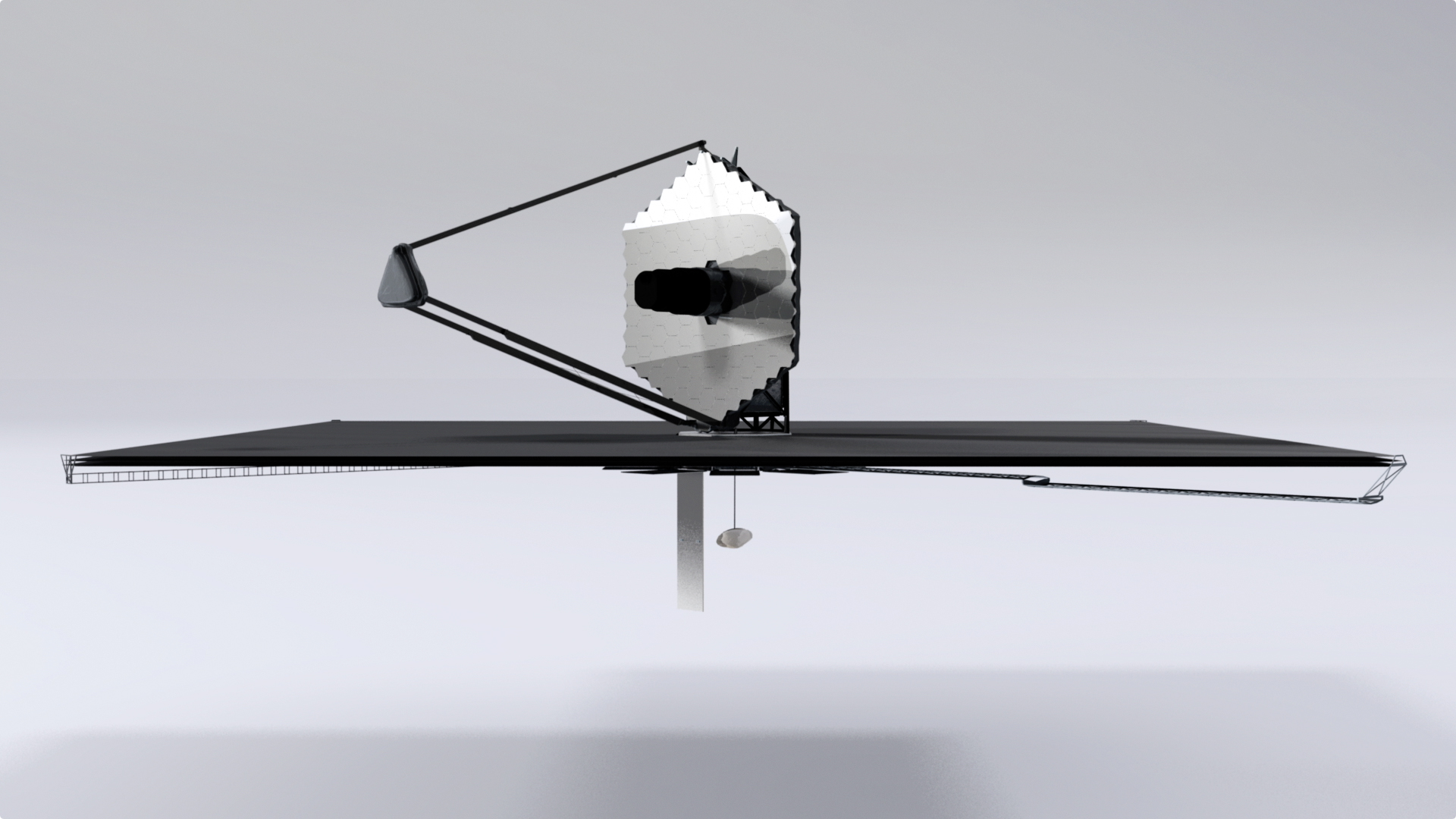

Because the report is focused on instruments that could get to work 15 or 20 years down the road, it only briefly discusses current projects, such as the recently launched Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, which began gathering data in late July, and near-term projects, like the James Webb Space Telescope (Webb), which is currently scheduled to launch in 2021. The committee did express support for those projects.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronomers have generally voiced their support for Webb's science goals, but that telescope has developed a reputation for being over budget and behind schedule. Christiansen worries that the new report's focus on similarly ambitious projects could end up being problematic if they also see cost and timeline problems. Big projects like Webb, she said, "just eat everybody else's lunch," and their stumbles have encouraged some scientists to focus on smaller projects instead. But that's not the case for the new report's authors.

"It's a really bold strategy to say we should put all our eggs in one basket," Christiansen said, adding that, while the approach comes with potential high rewards, it also comes with potential high risks. "If we've burned too many bridges with the previous missions and it doesn't work, then we're a little bit rudderless," Christiansen said. She was surprised not to see more talk in the report about the tiny, relatively inexpensive satellites called CubeSats and how they could contribute to exoplanet science, although report leaders specified during a press conference that these smaller missions would also be valuable.

But the committee behind the report thinks the big sticker prices on bold missions are worth it. "The costs of these telescopes and the missions that we're talking about, while substantial, are certainly not out of the scope of what we as a society can do," B. Scott Gaudi, an astronomer at The Ohio State University and co-chairman of the committee, told Space.com.

These costly projects are ambitious space telescopes like the Large Ultraviolet/Optical/Infrared Surveyor (LUVOIR) and the Habitable Exoplanet Observatory, which would each be powerful enough to separate the tiny light of a planet from the powerful glare of its star. They would also include funding giant, ground-based telescopes, like the Thirty Meter Telescope (possibly in Hawaii) and the Giant Magellan Telescope (in Chile).

That emphasis on direct imaging stood out to Thayne Currie, an astronomer at the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan not involved in the new report who focuses on that technique, which is currently extremely difficult. "[Direct imaging] is intriguing because seeing is believing," he told Space.com. "A lot of people, when you tell them that we don't actually directly detect many of the planets, it's kind of a head-scratcher."

Exoplanet detections right now tend to spot planets by the slight wobble their gravity causes in a star's position (called the radial velocity method) or by the slight dip in a star's brightness caused when a planet slips between the star and a telescope (called the transit method). In contrast, the report focuses on detection methods that require the next level of technology — direct imaging and microlensing, which uses an optical trick to magnify distant patches of space and will be possible with the WFIRST telescope, currently slated to launch in 2025.

Direct imaging also offers additional information about the planet itself and what might be happening on its surface. "Once you can see the planet you can do all kinds of interesting things," like study its orbit, begin to understand its composition, and perhaps spot signs of weather or rotation, Pat McCarthy, vice president for operations of the Giant Magellan Telescope who was not involved in the new report, told Space.com. "It really opens the world." [10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

Although the report emphasizes the appeal of determining habitability and searching for life, it strives to balance those questions with others related to exoplanets more generally. "The committee took a very holistic view on our charge of an exoplanet strategy," Gaudi said. "We do not believe it is possible to go out and identify life without understanding the context of that particular planet."

Although the report focuses primarily on science, it also addresses the scientists behind exoplanet research, calling for cross-disciplinary collaboration and support for research grants. The report also touches on encouraging diversity and preventing discrimination and harassment, although it does not offer any concrete recommendations on those topics.

All told, the new report sketches out a path for dramatically beefing up exoplanet studies over the next two decades, with potentially momentous consequences. "For the first time in human history, we now can embark, if we choose to, in answering the question of whether there's life on other planets," Gaudi said.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.comor follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.