Back in Action? Mars Rover Curiosity to Test New Drilling Technique Saturday

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

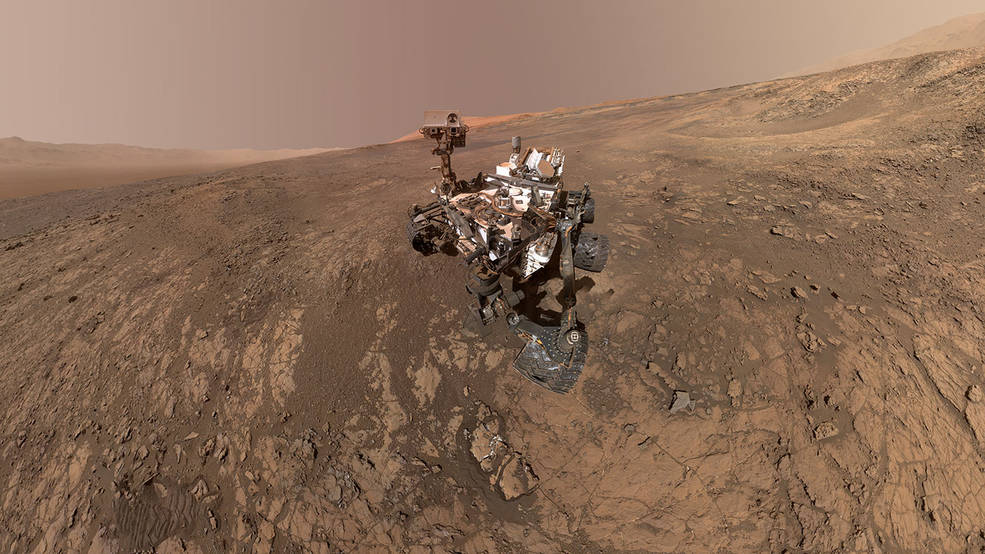

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity could get back to its old rock-drilling ways soon.

A mechanical problem knocked Curiosity's drill, which sits at the end of the rover's 7-foot-long (2 meters) robotic arm, out of commission in late 2016. Mission team members have been studying ways to get the drill back online ever since, and they plan to test a promising work-around this weekend.

Engineers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, are tweaking a technique called feed extended drilling (FED), which allows Curiosity to drill in a way similar to how a person might do it. Curiosity will use the force of its arm to push forward into Red Planet rocks as the drill bit spins. And FED will allow Curiosity to apply a hammering force as well, NASA officials said. [Photos: Spectacular Mars Vistas by NASA's Curiosity Rover]

This hammering was key to Curiosity's original drilling technique, allowing the rover to bore 2.5 inches (6.4 centimeters) into rock.

Curiosity will test the new technique, with the percussion component, on Saturday night (May 19), mission team members said. The resulting data will help engineers improve the drilling method over the next few months, the team said.

"This is our next big test to restore drilling closer to the way it worked before," Steven Lee, Curiosity deputy project manager at JPL, said in a statement. "Based on how it performs, we can fine-tune the process, trying things like increasing the amount of force we apply while drilling."

If the new technique allows Curiosity to snag a powdered-rock sample, the engineering team will "immediately begin testing a new process for delivering that sample to the rover's internal laboratories," NASA officials said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Curiosity has been steadily climbing the foothills of the 3.5-mile-high (5.5 kilometers) Mount Sharp since September 2014, studying the rocks for clues about how and when Mars' climate changed long ago. Such observations are key to the rover's mission, which involves assessing the Red Planet's past potential to host life.

Recently, the rover was making its way uphill along a landform called Vera Rubin Ridge. But last month, mission team members directed Curiosity a bit downhill, toward an area they'd like to sample. This change in direction reflects the team's confidence that Curiosity soon will be able to drill nearly as effectively as it once did.

"We've purposely driven backwards, because the team believes there's high value in drilling a distinct kind of rock that makes up a 200-foot-thick [about 60 m] layer below the ridge," Curiosity project scientist Ashwin Vasavada, also of JPL, said in the same statement. "We're fortunately in a position to drive back a short way and still pick up a target on the top of this layer."

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter@salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.