What Would It Mean for Astronomers If the WFIRST Space Telescope Is Killed?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

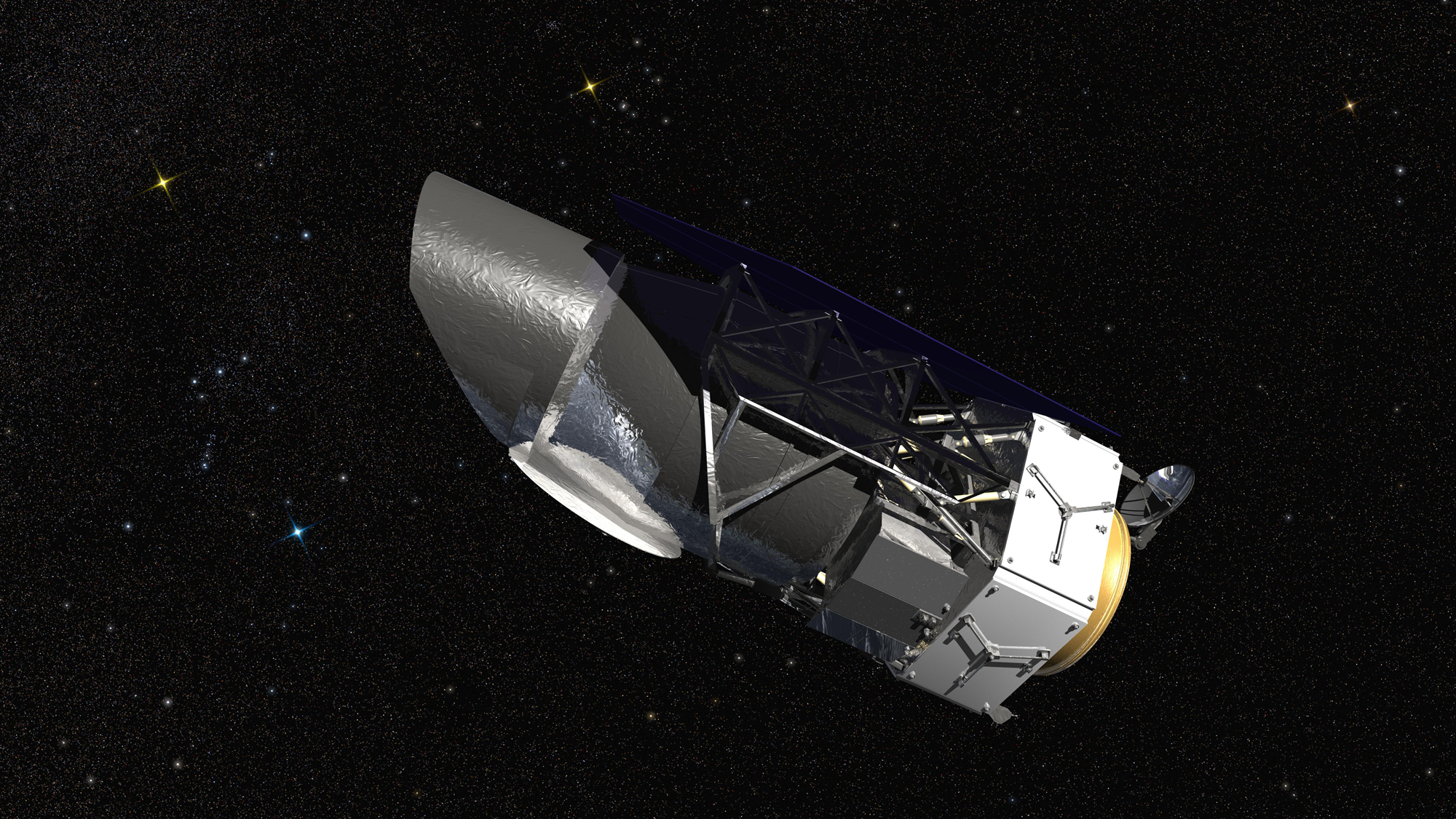

The White House budget proposal has called for the cancellation of the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), a move that could be interpreted as a warning to the mission's leaders to rein in the program's expanding costs. But if the cancellation goes through, some scientists worry it could hurt the international standing of the U.S. astrophysics community.

WFIRST was tentatively scheduled to launch in the mid-2020s, to become NASA's next "flagship mission," a classification applied to large-scale missions with broad science objectives. Other NASA flagship missions include the Hubble Space Telescope, the Chandra X-Ray Telescope, and the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope.

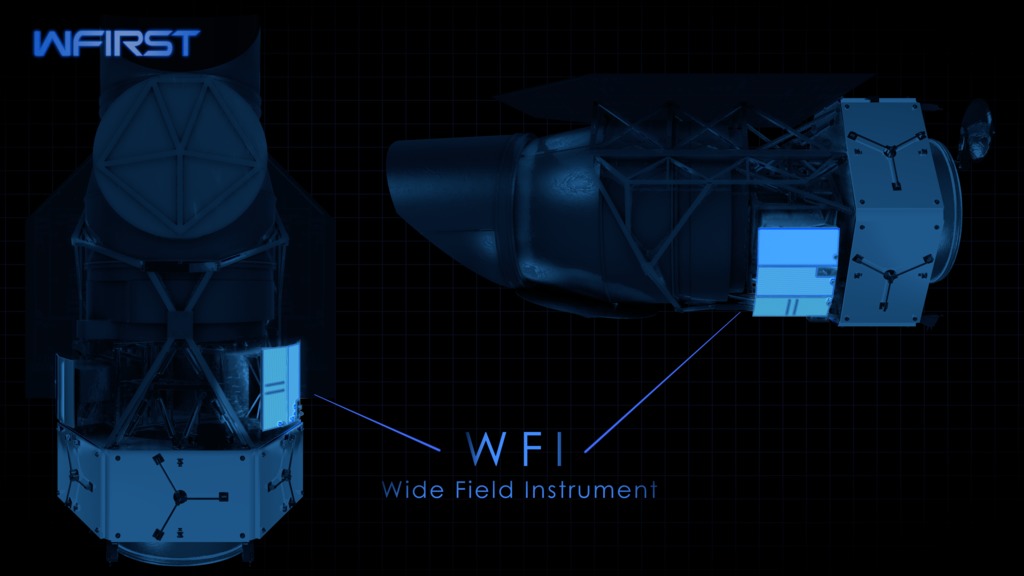

Among its many science capabilities, WFIRST was designed to search for and study planets around other stars, and answer key questions in cosmology. That also included a focus on understanding the nature of dark energy, that mysterious force that is believed responsible for the universe's accelerating expansion. David Spergel, a physicist at Princeton university and co-chair of the WFIRST science team, wrote on Twitter about the value of WFIRST, citing some of the many questions that it could help scientists answer.

"What is driving the acceleration of the universe? What are the properties of exoplanet atmospheres? How did our galaxy and its neighbors form and evolve? What determines the architecture of exoplanets? US should be leading the world in addressing these big questions," he wrote.

The importance of WFIRST's science program was emphasized when it was selected as the top mission priority for the U.S. astronomy and astrophysics community in the 2010 decadal survey titled New Worlds, New Horizons in Astronomy and Astrophysics. That report, put out once every 10 years by the National Academy of Sciences, is a multiyear project that ultimately provides a roadmap for funding agencies regarding which missions or mission concepts should be pursued. Typically, NASA (as well as other agencies like the National Science Foundation) follow the recommendations of the decadal survey.

"I think it's a poor decision and an unnecessary one," Spergel told Space.com regarding the decision to cancel WFIRST. "I see it as abandoning U.S. leadership in space astronomy. Canada, Japan, the European Space Agency, France — they are all ready to partner with us and make contributions to the mission. They join in because they think this is something we'll do, because it's our top [decadal survey] priority."

"I think if it's cancelled it'll be a terribly sad day for the community," Roger Blandford, a physicist at Stanford University who chaired the 2010 decadal survey committee, told Space.com. "WFIRST was the top-rated space mission from the decadal survey. That was a community-wide, bottom-up process, and [the mission] emerged with this ranking after a large number of people had been involved."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In addition to WFIRST's capabilities in cosmology and exoplanet science, the program would allow researchers in other fields to apply for time and use WFIRST for other types of space research. That would "open the door for an unscripted discovery," Blandford said, adding that "It was that broad user base, I think, that led to a lot of people really liking it as a mission."

Andrew Hunter, NASA's acting chief financial officer, told reporters in a telephone news conference yesterday (Feb. 12) that WFIRST was not cut due to "prejudice against the science."

In its 2019 NASA budget proposal, the White House mentioned cost as its reason for cutting the mission, noting that the program would require budget increases in coming years. (In the budget proposal, some of the money that would have funded WFIRST will be redirected to "exploration activities," according to Hunter, which include efforts to send humans back to the moon. Money was also diverted to lunar exploration activities from Earth science and education.)

WFIRST is still in the concept and planning stages, and the early stages of construction, when mission members solidify the scope of the mission's concept and clarify the technology it will use. But for years, the mission's estimated budget has been swelling beyond the initial projection of a $2 billion life-cycle cost, to an estimated $3.6 billion as of 2017. (For comparison, the Webb telescope is now expected to cost about $8.8 billion over its lifetime; Hubble's lifetime cost has exceeded $10 billion, although both of those telescopes have a more diverse array of science instruments than WFIRST.)

In 2016, the National Academies put out a midterm report to reassess the priorities that were set in the decadal survey in 2010. The report reiterated that NASA should continue with the WFIRST mission, but it also noted that WFIRST's budget was swelling to dangerous levels.

In response to that report, in April 2017, NASA assembled an independent review panel to investigate the WFIRST cost overruns. The panel's report found that the instrument's design had become more complex than originally planned. In October, Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA's science mission directorate, announced that he was directing the WFIRST mission team to come up with a plan to keep the budget under $3.2 billion. The results of that effort are scheduled to be presented to the NASA directorate in March.

It's possible that the budget proposal is the Trump administration's way of telling NASA to keep the WFIRST budget on track, according to Marcia Rieke, an astronomy professor at University of Arizona and the Seward Observatory.

"Canceling it may be … sending a message to the people building it that it's not just the mid-decadal review that says they need to get back into the cost box," she said. "It's a harsher form of what has already been said in several other venues."

Rieke is co-chair of the National Academy of Sciences' Committee on Astronomy and Astrophysics, which is "chartered with looking out for how the decadal survey recommendations are being implemented by our funding agencies," she told Space.com. If WFIRST is to be revived during budget discussions in the House and Senate, she said it will need some strong supporters.

Sen. Bill Nelson, D-Fla., a former space shuttle astronaut, said in a statement to the Orlando Sentinel that "the administration's budget for NASA is a nonstarter." Nelson's objections to the budget were largely focused on the termination of government support for the International Space Station in 2025, but he also noted the "deep cuts to … science programs."

"If the astronomy community and those who are interested in astronomy push back, we will be able to reverse the cuts in the astronomy budget," Spergel wrote on Twitter. "These cuts imperil not only WFIRST but any future major mission. Push back!"

But if WFIRST does get canceled, it will leave the astronomy community with the difficult challenge of figuring out how pursue the science goals of the mission.

"WFIRST was the top space recommendation in the 2010 astronomy decadal survey. That gives an indication of how important the science is to the community," Rieke said. "If one canceled [WFIRST], that science still needs to be done. And it can only be done by a space mission. So, it'll be interesting to see how we proceed … We'll have to think through how to achieve that science starting all over again."

Editor's Note: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Marcia Rieke is a professor at the Massachusetts Insittute of Technology; she received her PhD at MIT but is currently a professor at University of Arizona.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter