'In Search of Stardust': Photo Book Highlights the Beauty and Mysteries of Tiny Space Rocks

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A new book zooms in on micrometeorites — incredibly small, surprisingly complex, undeniably beautiful space rocks that liter the surface of the Earth.

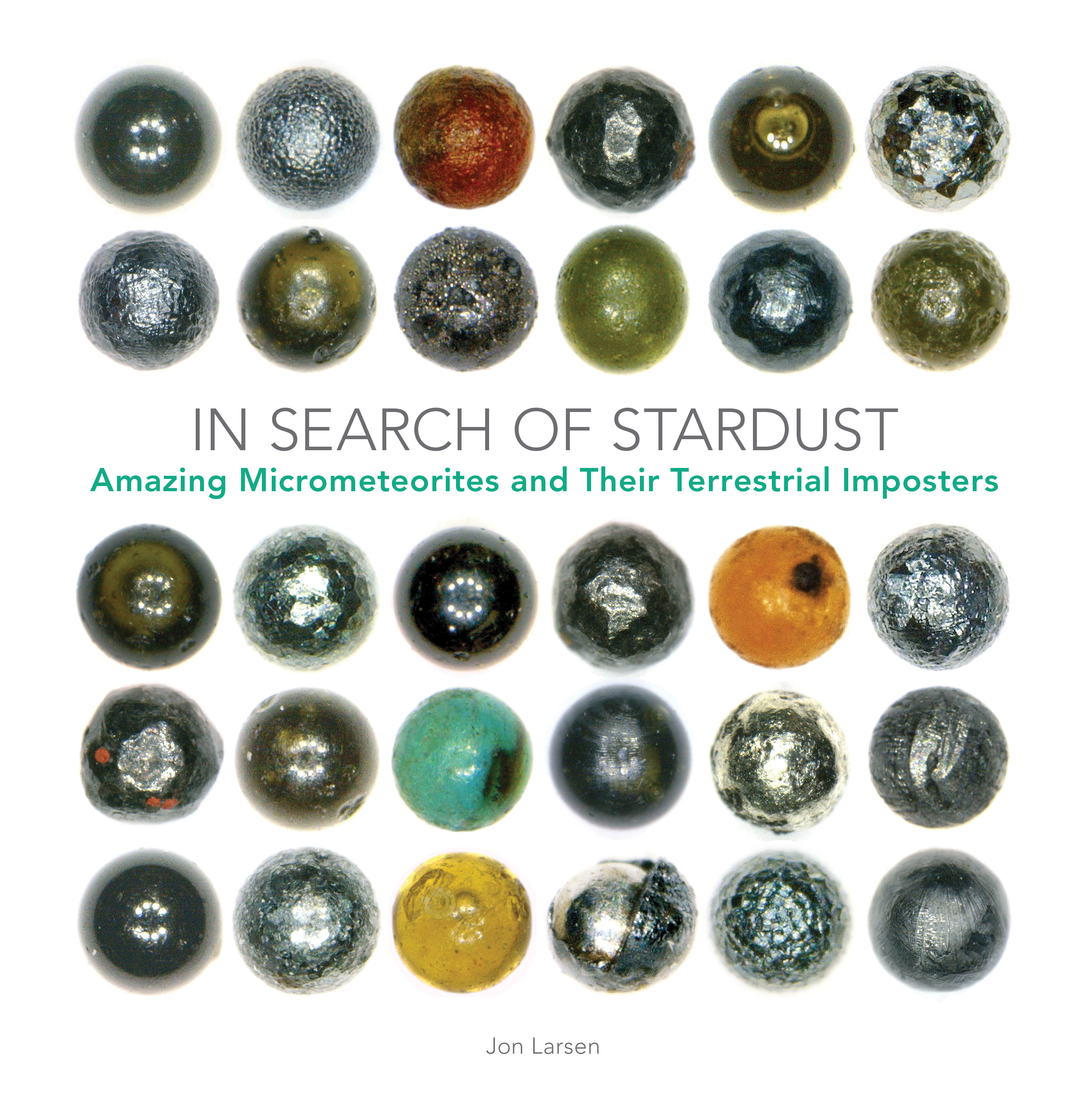

"In Search of Stardust: Amazing Meteorites and Their Terrestrial Imposters" is primarily a photography book. It contains hundreds of images of micrometeorites — averaging between 0.2 and 0.4 millimeters — that traveled through the cold reaches of space before hurtling through Earth's atmosphere.

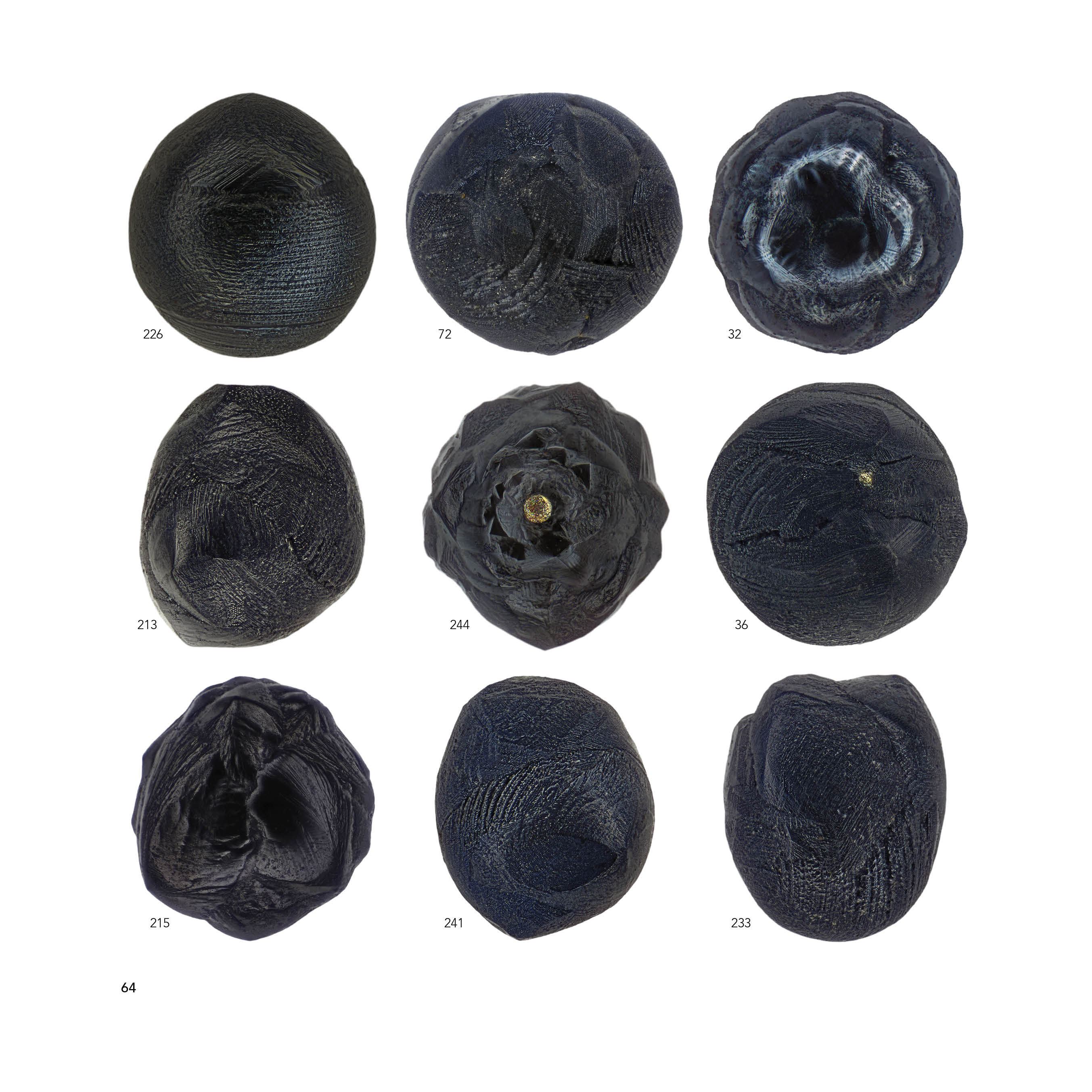

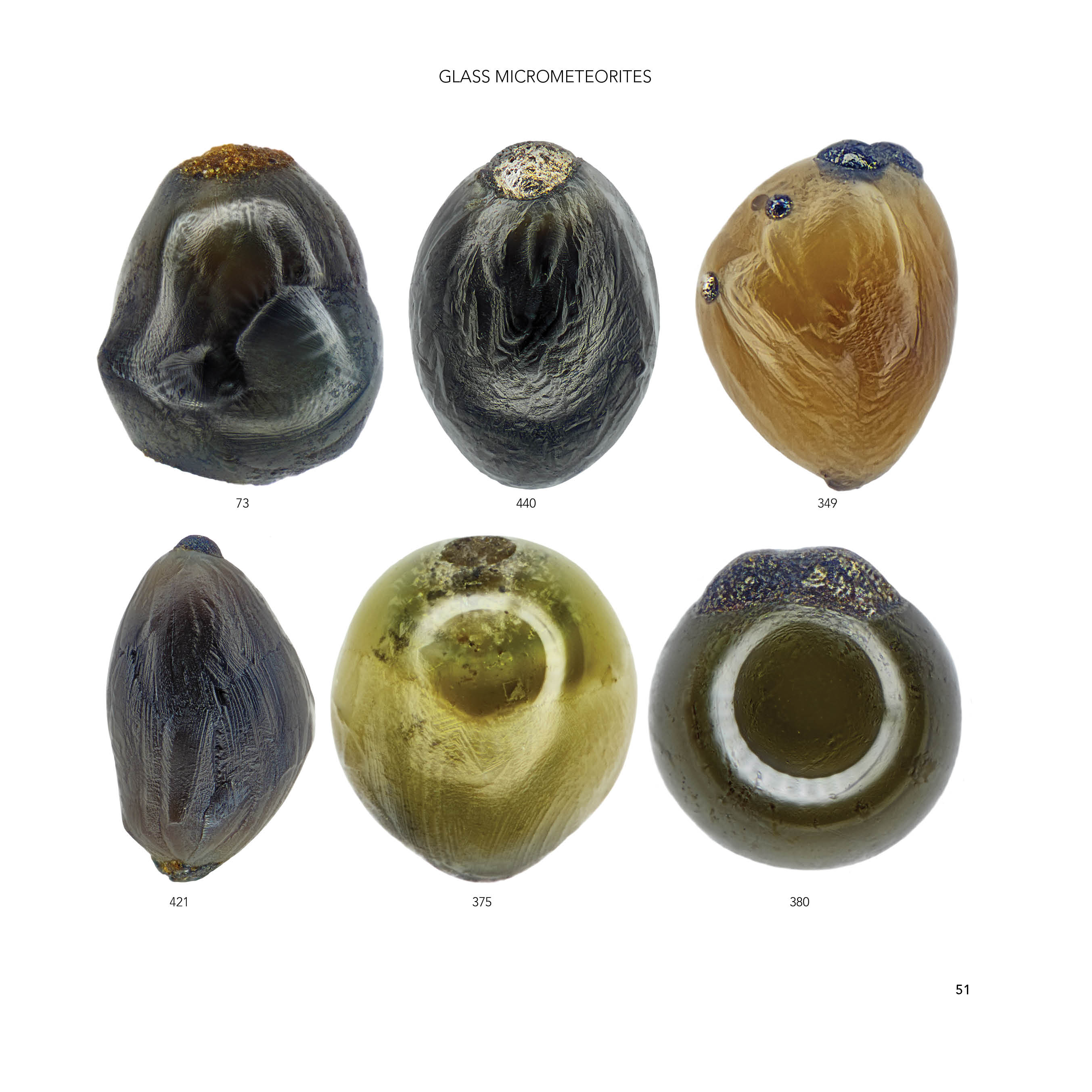

Just like snowflakes, no two micrometeorites are exactly alike. Captured using various methods of magnification, the images in "In Search of Stardust" show the intricate surface textures found on micrometeorites. Some are covered in consecutive ridges, bumps and ripples, similar to the multitude of patterns that can arise on the surface of a lake during rough winds. One micrometeorite is dotted with protruding pyramids that make the whole thing look somewhat like a strange, 3D soccer ball. Many of the oblong space rocks feature a lump of material at one end that look different from the rest of the meteorite's surface — an indication of the rock's long, arduous journey, perhaps? ['In Search of Stardust' in Pictures: Micrometeorites and More]

The book documents the results of an effort called the Stardust Project, which aimed to find and identify micrometeorites in populated areas. Historically, the book explains, researchers hunted for these tiny space rocks in regions where there was very little human interference. But that method eliminates many potentially ripe hunting grounds. The book's author, Jon Larsen, initiated the project and eventually collected micrometeorites from nearly 50 countries, according to the book. His photo database contains images of more than 40,000 individual objects.

How does someone know if a very tiny rock came from space? Larsen dives into the details in his introduction, and more than half of the book focuses on other types of miniature "spherules" and the ways they differ from true micrometeorites. For example, there are images of "extraterrestrial spherules" that break off of larger meteorites only after the parent rock has fallen through the atmosphere. (A true micrometeorite makes the journey alone). There are also photos of human-made spherules; these often come from processes such as welding, so most of those spheres have a metallic shine. The book also features some fascinating and beautiful photographs of a wide variety of naturally occurring spherules that have undergone similarly intense processes on Earth. These bits of material can be organized into subgroups, with names like Darwin glass, fulgurites, volchovites, ooids and pisoids.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In a statement about the book, the publisher says there is no other book quite like "In Search of Stardust," and we'd have to agree. (Larsen recommends some more academic works for anyone interested in taking a deep dive into the study of micrometeorites.) The book is light on text, but its images work to convey the very big story of these very small rocks, some of which might be older than planet Earth, or might have traveled across billions of miles of space and just happened to land on our own little blue spherule. The beauty of the photographs will likely capture anyone's eye but will be an especially wonderful treat for anyone who is fascinated by the microscopic world, or by the incredible life stories of these micrometeorites.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter