Early Meteorite Bits Reveal Clues About Solar System's Evolution

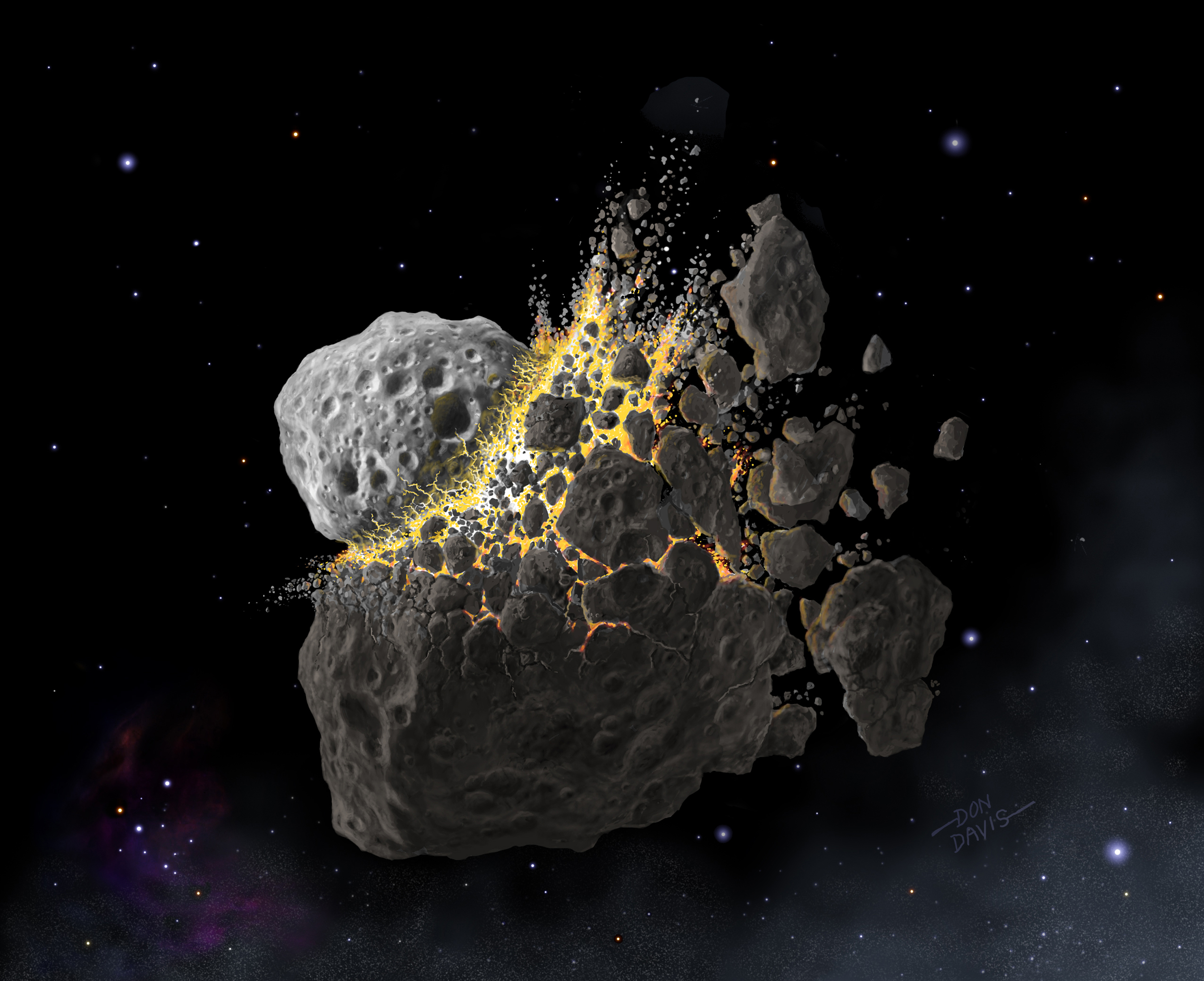

Many meteorites found on Earth are remnants of one titanic solar-system collision that took place more than 460 million years ago. But for the first time, researchers have specifically targeted meteorites that fell to Earth just before that asteroid collision and found that the composition of those earlier space rocks is quite different than those today.

By sifting through the minuscule remnants of those ancient solar-system crashes, called micrometeorites, the researchers found that the most common types of meteorites today used to be quite rare — and the rarest ones used to be common. Understanding the makeup of asteroids provides insight into the history of solar-system collisions and the evolution of the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, scientists say.

"We spend lots of time studying the debris from the big asteroid destruction event 466 million years ago, but recently, we went a little bit further back in time," said Philipp Heck, a researcher at The Field Museum in Chicago and lead author of the new research paper. "We found it very different from what comes down today — that was our big surprise," Heck told Space.com. [The Strangest Asteriods in the Solar System]

Meteorites come from flying debris after a collision of two bodies in the solar system, and their makeup reflects the asteroid, comet, moon or planet that suffered through the crash. The rarest meteorites found on Earth today come from differentiated or partially differentiated bodies — big clusters of dust and debris that got hot enough to form (or partially form) a core, mantle and crust, as on Earth, Mars or the asteroid Vesta. It's much more common for meteorites today to come from undifferentiated bodies, which remained mixtures of rock, dust and metal.

But according to the new research, that type of meteorite, called an ordinary chondrite, used to be much less common than ones from differentiated bodies were. By avoiding the most recent meteorites, researchers can get a glimpse of more collisions in the solar system's past.

"This is not an event, what we're looking at — this is basically the background," Heck said. "You can say these are tails of different events; the results of different [collision] events in the solar system, in the asteroid belt, that generated fragments … and those fragments arrived to Earth."

A few events and asteroid populations seem to dominate that background, he added: 34 percent of the micrometeorites came from partially differentiated bodies, which had partially melted and begun to separate out, whereas only 0.45 percent of meteorites today are that type. This indicates that many more of those bodies were experiencing collisions in the past, Heck said. The researchers also found micrometeorites that originated from a collision at Vesta, the brightest asteroid visible from Earth, billions of years ago, as well as meteorites that the researchers think came from the formation of the Flora asteroid family, also about a billion years ago. Both reside in the asteroid belt.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Notably, there were very few ordinary chondrites — most were generated later, by the 466-million-year-old collision or by an even later event, which generated another type of ordinary chondrite, Heck said.

"Using relict minerals in the rock record to determine the previous asteroid flux is incredibly inventive," Tasha Dunn, a planetary geologist at Colby College who was not involved in the research, told Space.com by email. "I was quite surprised by the results."

Dunn noted that the proportions of meteorite types that rain down today don't match the populations of asteroids found in the belt — a disparity that has puzzled meteorite researchers. "Trying to understand why the proportion of asteroids in the asteroid belt doesn't match what we see in the meteorite collection has been one of the biggest questions in meteorics for some time," she said.

Dunn said she was particularly interested in seeing the large proportion of meteorites from the Flora family back then, because researchers have wondered why there weren't many of them coming down despite the Floras' good position. Maybe, she said, much of the material was expelled during the initial breakup of the family. [The Asteroid Belt Explained (Infographic)]

"Needle in a haystack"

Understandably, meteorites that fell more than 466 million years ago are difficult to find. Heck's Russian and Swedish colleagues turned to micrometeorites less than 2 millimeters (0.08 inches) across. By sifting through samples of rock from a river valley in Russia that used to be seafloor, they managed to separate some. They chose a location that would have had a slow buildup of sediment, leading to a greater proportion of the desired micrometeorites.

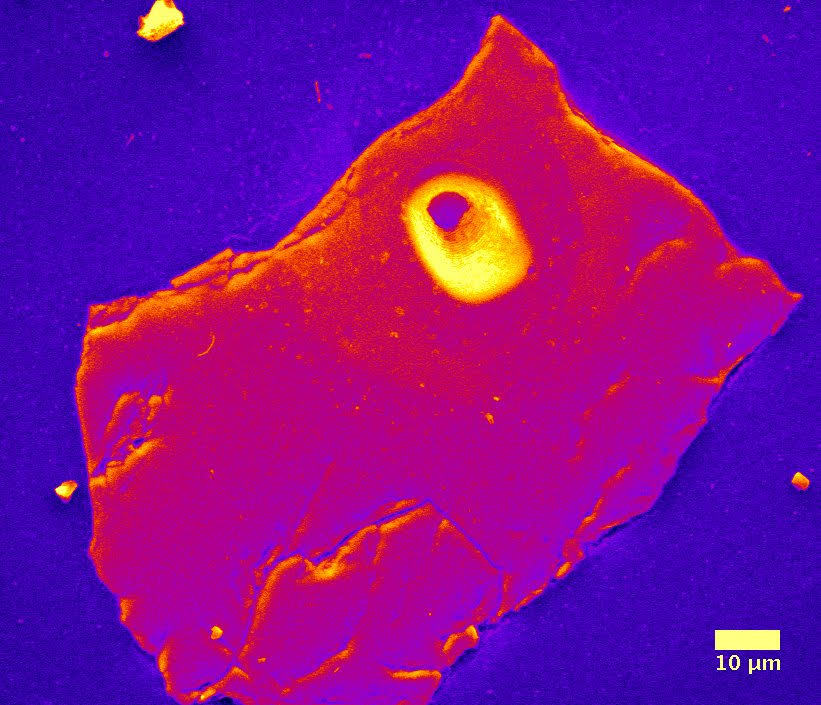

The researchers took advantage of a lucky fact: chromites and chrome spinels, the key grains necessary to determine the age and makeup of a micrometeorite, are resistant to acid. So to find the meteorite compounds, they treated the material with hydrochloric or hydrofluoric acid to eat away the Earthly sediments, leaving the meteorite markers behind.

"The approach is essentially a needle-in-a-haystack problem, and we use the crude method of burning down the haystack to find the needle," Heck said.

Heck's group analyzed samples dating back from the target era, zeroing in on the chromites and chrome spinels whose makeup can help scientists classify the type of object they came from.

"Even almost 500 million years in the sediment didn't change them," Heck said. "They still preserve the original composition, which makes it a really, really good and robust mineral to study meteorites that arrived in the past."

They also measured the oxygen isotopes — that is, oxygen with different numbers of neutrons — whose proportions likely represent how far from the sun the body formed, Heck said.

Going forward, Heck said, researchers should look at different time windows to try to understand those earlier solar system collisions, like the one that blasted fragments off of Vesta.

"We can do that for the different types of fragments from different parent bodies, parent asteroids, and get a better picture of what collisions happened and what were the effects on planets in the inner solar system," he said. One could also track meteorite fragments on places like the moon and Mars for a more complete view. All results can be fitted into models of the events, increasing their accuracy and our understanding of the solar system's evolution — and, potentially, those titanic crashes' impact on Earth's life and climate.

"It's really a multidisciplinary collaboration with different fields — geology, cosmochemistry, planetary science, chemistry — all working together to try to tackle that problem," Heck said.

The new research was detailed today (Jan. 23) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.