Cassini's Journey into the Unknown: NASA Engineer Talks Saturn Risks & Rewards (Video)

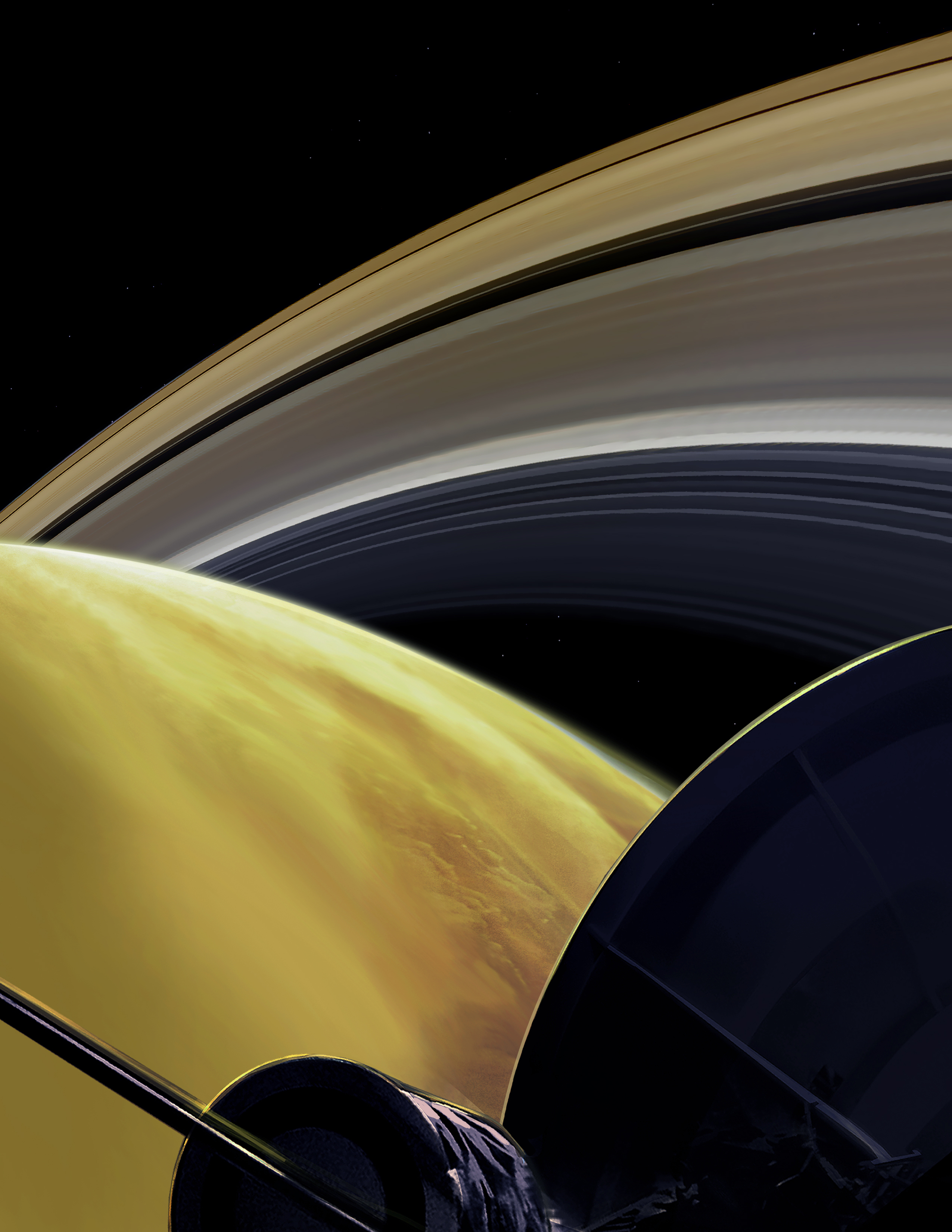

NASA's Cassini spacecraft has gone where no craft has ventured before: diving through the narrow gap between Saturn and its icy rings for the first of 22 planned plunges before it dives into Saturn's atmosphere Sept. 15.

Space.com talked with Joan Stupik, a guidance and control engineer for Cassini at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, about the risks of that first pass between the planet and rings and what scientists hope to learn over the course of its unprecedented journey. You can view a video of the conversation here.

At the time of the interview, Cassini had already passed through the 1,200-mile gap (1,900 km), but scientists on Earth had yet to hear back from the spacecraft — Cassini turned around to use its antenna as a shield, and wasn't set to report back until early this morning (April 27). [Cassini's "Grand Finale" at Saturn in Pictures]

"The ring scientists have spent a long time, more than a decade, characterizing those rings, but that small gap between the inside of the innermost ring and the top of the atmosphere where the ring ends isn't known fully," Stupik told Space.com. "We think that it's clear of debris, but there's a small possibility that there could be small bits of debris particles, flecks of dust in there … going up to 45 times the speed of a bullet."

In fact, Cassini will use that same maneuver when necessary as it explores different parts of the gap over the next 21 dives, Stupik said.

"The risk to the spacecraft varies based on where we're crossing that gap," she said. "We have plans in place; if the area is more thick with debris than we expect, then the engineers are ready to make last-minute changes to how we go through the ring … [to] use the antenna as a shield just for that little time that we're crossing through the rings," she said.

Whenever the coast is clear, though, scientists will be free to orient Cassini to gather as much data as possible about the planet and rings from their new perspective.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This is the first time we're going to be able to look at the rings and Saturn separately," Stupik said. "We'll be able to learn how old the rings are, and that will tell us a lot of information about how they were formed, and also to learn about what the interior of Saturn looks like; how big is the core, what is the inside made of, how does the magnetic field work."

By the way, she added, whether or not Cassini meets with misfortune along the way, like an unexpected piece of debris, it's still gravitationally set for its final plunge into the planet's atmosphere Sept. 15. The only question is whether scientists are able to catalog its journey.

Cassini's final dive was one of two potential endings for its 13-year exploration of Saturn's system — both were intended to protect the planet's moons from contamination that could distort our future searches for the building blocks of life.

"Because Cassini has learned of two moons at Saturn, both Titan and the moon Enceladus, that could harbor life as we know it, the requirements are that we have to make sure that Cassini cannot possibly contaminate one of those moons," Stupik said. (JPL scientists have clarified that protecting Titan from further contact is a bonus — a lander has already explored that moon as part of the mission. Geyser-blasting Enceladus is the main target of the protection standards.)

"Because we're almost out of gas, and we have no way of refilling — the nearest gas station's a billion miles away back on Earth — our choices were either to throw it out really far away from Saturn so it would never crash, or to dispose of the spacecraft inside of Saturn," Stupik added.

The scientists and engineers of the Cassini mission chose the second option — to learn as much about the planet as possible in one final, epic dive, collecting data about the planet's mysteries, which scientists will be analyzing for years to come.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.