Cassini Saturn Probe Survives 1st 'Grand Finale' Dive

NASA's Cassini spacecraft has survived its first plunge through the narrow gap between Saturn's cloud tops and the giant planet's innermost rings, a region that no probe had ever explored before.

The space agency's Deep Space Network Goldstone Complex in California picked up Cassini's signal at 11:56 p.m. PDT yesterday (April 26; 2:56 a.m. EDT and 0656 GMT today, April 27) — nearly a full day after the historic dive took place. Data began coming in from the probe 5 minutes after contact was established, NASA officials said.

"In the grandest tradition of exploration, NASA's Cassini spacecraft has once again blazed a trail, showing us new wonders and demonstrating where our curiosity can take us if we dare," Jim Green, director of NASA's Planetary Science Division, in Washington, D.C., said in a statement. [Cassini's 'Grand Finale' Saturn Orbits Explained (Video)]

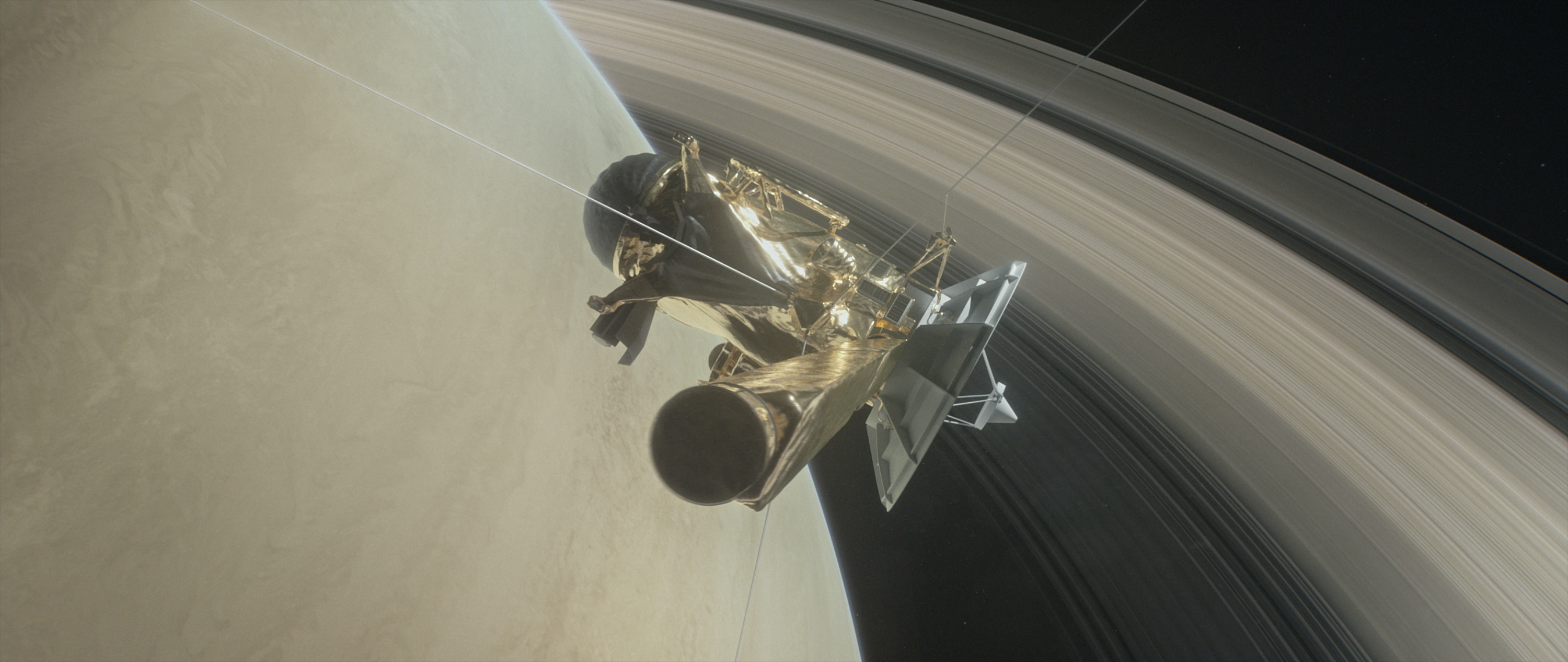

Cassini zipped through the gap at 2 a.m. PDT (5 a.m. EDT and 0900 GMT) yesterday, coming within about 1,900 miles (3,000 kilometers) of Saturn's upper atmosphere and 190 miles (300 km) of the visible edge of the innermost rings, NASA officials said.

The probe crossed the ring plane at about 77,000 mph (124,000 km/h) relative to Saturn, they added — fast enough that a collision with even a small particle could have seriously damaged Cassini. To minimize that possibility, the spacecraft used its dish-shaped, 13-foot-wide (4 meters) high-gain antenna as a shield during the dive.

Because the antenna was oriented toward incoming particles, Cassini couldn't communicate with Earth as it dove. The probe was programmed to gather science data during the plunge and then re-establish contact with mission controllers 20 hours later, NASA officials said. (It currently takes 78 minutes for signals to travel from Cassini to its handlers here on Earth.)

"No spacecraft has ever been this close to Saturn before. We could only rely on predictions, based on our experience with Saturn's other rings, of what we thought this gap between the rings and Saturn would be like," Cassini project manager Earl Maize, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in the same statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I am delighted to report that Cassini shot through the gap just as we planned and has come out the other side in excellent shape," Maize added.

Cassini is scheduled to perform 21 more of these dives during the current "Grand Finale" phase of its mission, with the events occurring about once every week. The next plunge will come on May 2.

The $3.2 billion Cassini-Huygens mission — a joint effort involving NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency — launched in October 1997 and reached the Saturn system in July 2004. (Huygens was a piggyback lander that touched down on Saturn's largest moon, Titan, in January 2005.)

Cassini has made a series of remarkable discoveries during its nearly 13 years of orbiting the ringed planet. For example, the probe spotted seas of liquid hydrocarbons on Titan and geysers of water ice, as well as organic molecules and other materials, blasting from the south polar region of fellow Saturn satellite Enceladus. Further Cassini observations have revealed that Enceladus harbors a potentially habitable ocean of liquid water beneath its icy shell.

But Cassini is running out of fuel, and its mission will soon come to an end. The spacecraft will perform an intentional death dive into Saturn's thick atmosphere on Sept. 15, to ensure that it doesn't contaminate Titan or Enceladus — both of which may be capable of supporting life — with microbes from Earth.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.