4 NASA Satellites to Seek Energy Eruptions in Earth's Magnetic Field

NASA is gearing up to launch a quartet of new satellites this month, to study a driving force behind solar storms that threaten Earth's satellites and power grids.

The satellites, which make up NASA's Magnetospheric Multiscale mission (or MMS), will launch on March 12 from Florida's Cape Canaveral Air Force Station to study a phenomenon known as magnetic reconnection in the magnetic field around Earth.

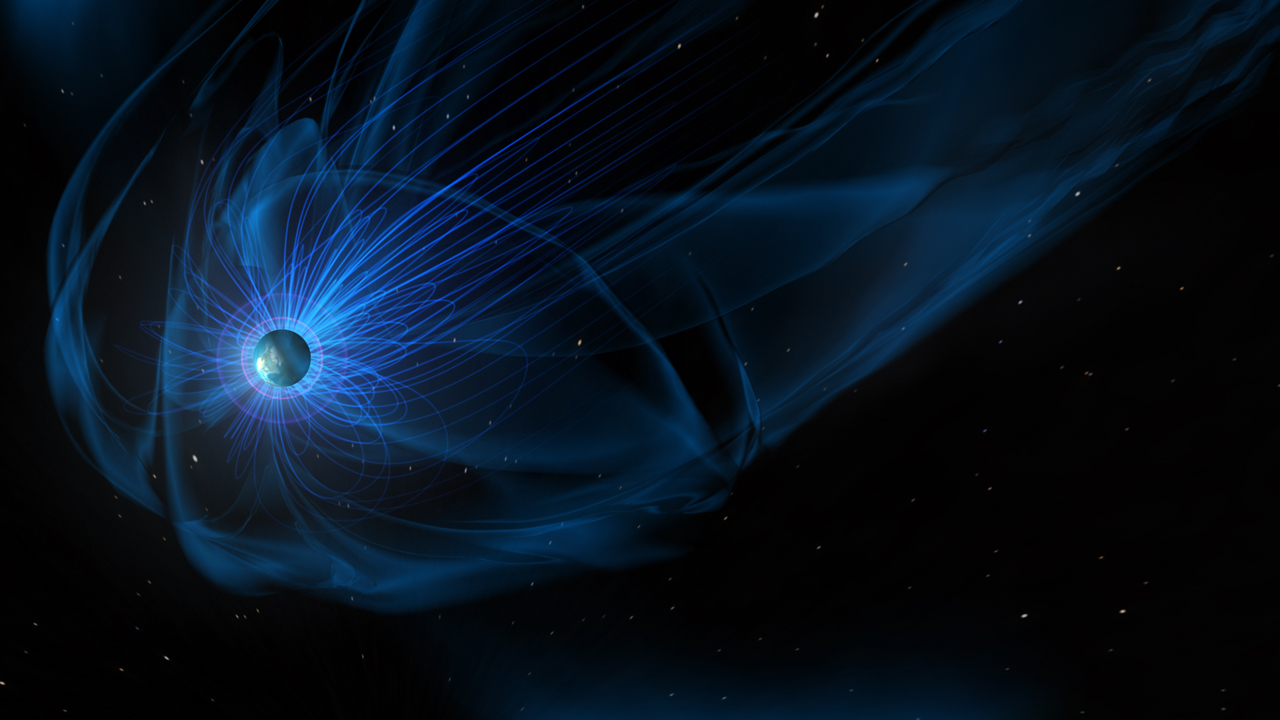

Magnetic reconnection occurs when magnetic field lines break apart and reconnect, releasing huge amounts of energy and charged particles — sometimes straight at the Earth. While scientists have studied magnetic reconnection for decades in an effort to better understand its relation to space weather and solar storms, the MMS satellites will be the first experiment to intentionally pass directly through areas where the phenomenon occurs and create a three-dimensional view of it, mission scientists said. [Worst Solar Storms in History]

The two-year MMS mission will conduct "a definitive experiment in space that will finally allow us to understand how magnetic reconnection works," Jim Burch, principal investigator of MM's Instrument Suite, said in a news briefing last week.

Magnetic fields are pervasive in the universe: the sun, the Earth, many other planets and stars, black holes and other objects generate powerful forests of magnetic field lines. Magnetic reconnection also occurs in many of these places.

In the sun, looped magnetic field lines are occasionally illuminated, and can be seen popping up through the star's fiery surface. Less visible are the magnetic field lines that reach out into the solar system, all the way to Earth's front door.

The sun's magnetic field lines bump up against the protective magnetosphere created by Earth's magnetic field, and reconnection occurs: the field lines snap apart like rubber bands, only to find other disconnected lines to merge with. This process turns magnetic energy into heat and kinetic energy, often sending showers of powerful particles toward the planet.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The MMS mission will send four, 3,000-lb. (1,360 kilograms) spacecraft into orbit around the Earth and take measurements from two primary locations where magnetic reconnection occurs.

The blasts of hot particles that reach the Earth's atmosphere can be harmless, or even beautiful: they excite particles of gas above the Earth, causing them to radiate light, which creates the dazzling displays known as auroras, or the northern and southern lights.

"The particles can cause problems too," Paul Cassak, an associate professor at West Virginia University, Morgantown, said in the Feb. 25 news briefing. "There's a number of satellites in space that we use for very important things like cellphone communication and GPS. If these particles run into the satellites they can short out the circuits and can knock out the satellites."

"The moving magnetic fields can also drive electric currents on the Earth and that can overload transformers and lead to power outages, which has happened in Canada and the United States and parts of Europe," Cassak said. "So all of these are aspects of what's known as space weather. So you can see that magnetic reconnection plays a very important part in space weather, and that's why it's important for us to study the fundamental science of magnetic reconnection so we can understand it."

NASA already has a fleet of spacecraft dedicated to studying the sun and space weather, both for scientific purposes, and to protect satellites and power grids.

"We're studying the sun, how the solar storms erupt from the sun, how they travel through space, how they interact with the Earth's magnetic environment," Jeff Newmark, interim director of NASA's Heliophysics Division, said at the news briefing. "So we need this whole system together. MMS is going to fill a key part of this system."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter