Extreme Space Weather Storms Spark Satellite Failures, Study Suggests

High-speed eruptions of charged particles from the sun may be to blame for recent failures of satellites that people rely on to watch TV and use the Internet, scientists say.

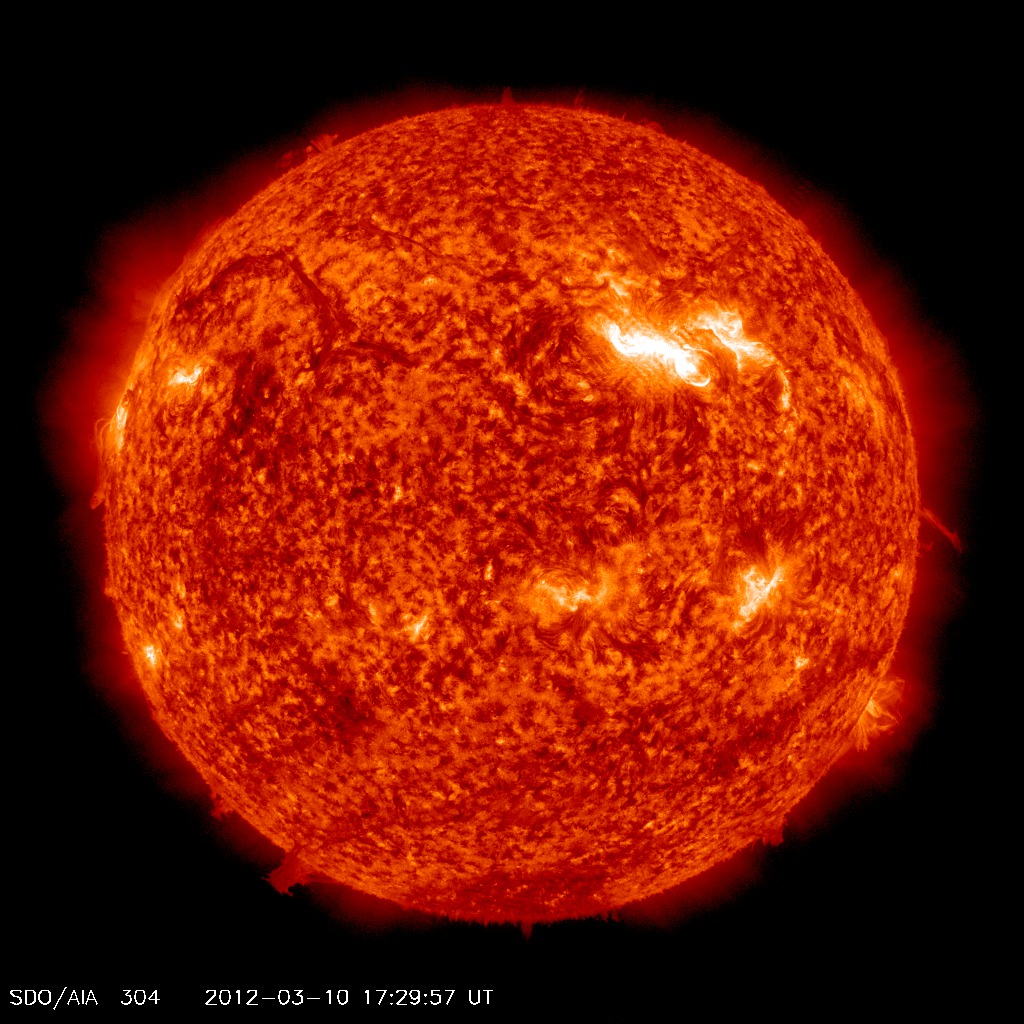

From 93 million miles (150 million kilometers) away, the sun spawns solar flares, coronal mass ejections and other space weather events, which can send highly energized particles racing toward Earth. Some solar storms have been known to disrupt communications systems and damage satellites.

To better understand these disturbances, a team of MIT researchers investigated the space weather conditions at the time of 26 failures in eight geostationary satellites operated by the London-based company Inmarsat. Geostationary satellites orbit at the same rate as the Earth’s rotation, meaning they always hover above the same location on the planet. [The Sun's Wrath: Worst Solar Storms in History]

Most of the glitches, from 1996 to 2012, coincided with high-energy electron activity during declining phases of the solar cycle, the study found.

The researchers think these charged particles may have accumulated in the satellites over time. Despite protective shielding, the buildup likely caused internal charging that damaged the satellites' amplifiers, which are needed to strengthen and relay a signal back to Earth. Over an extended mission, the researchers warn that this phenomenon could also cause the satellites' backup amplifiers to fail.

"Once you get into a 15-year mission, you may run out of redundant amplifiers," study researcher Whitney Lohmeyer, a aeronautics and astronautics graduate student at MIT, said in a statement. "If a company has invested over $200 million in a satellite, they need to be able to assure that it works for that period of time. We really need to improve our method of quantifying and understanding the space environment, so we can better improve design."

Space weather can be much more dynamic than predicted by the models engineers use when crafting satellites, explained Kerri Cahoy, a co-author of the study and an assistant professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"There are many different ways that charged particles can wreak havoc on your satellite's electronics," Cahoy said in a statement. "The hard part about satellites is that when something goes wrong, you don't get it back to do analysis and figure out what happened."

Lohmeyer and Cahoy's findings also suggest that some assumptions about solar storms and space weather risks may need to be revised. Researchers often take geomagnetic disturbances into consideration when assessing the vulnerability of spacecraft to space weather, according to a statement from MIT. But Lohmeyer found that most of the amplifier breakdowns occurred during times of low geomagnetic activity that would normally be considered safe.

"If we can understand how the environment affects these satellites, and we can design to improve the satellites to be more tolerant, then it would be very beneficial not just in cost, but also in efficiency," Lohmeyer added.

The team's research is detailed in the journal Space Weather.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @SPACEdotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.