Do Gravitational Waves Cause Tiny Earthquakes?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Earth can serve as a giant detector for theoretical ripples in the fabric of space-time given off by stars, black holes and other massive objects in deep space, researchers say.

The moon could be employed in the same way and potentially return even better results, scientists added.

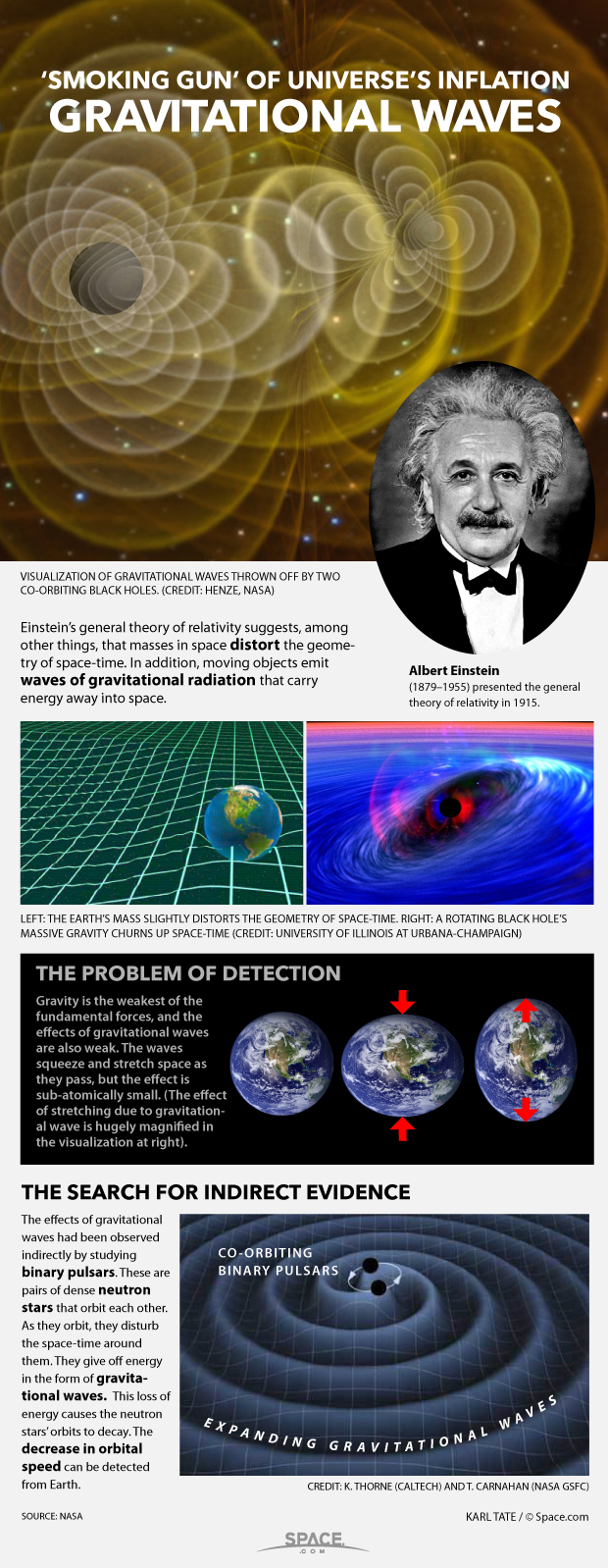

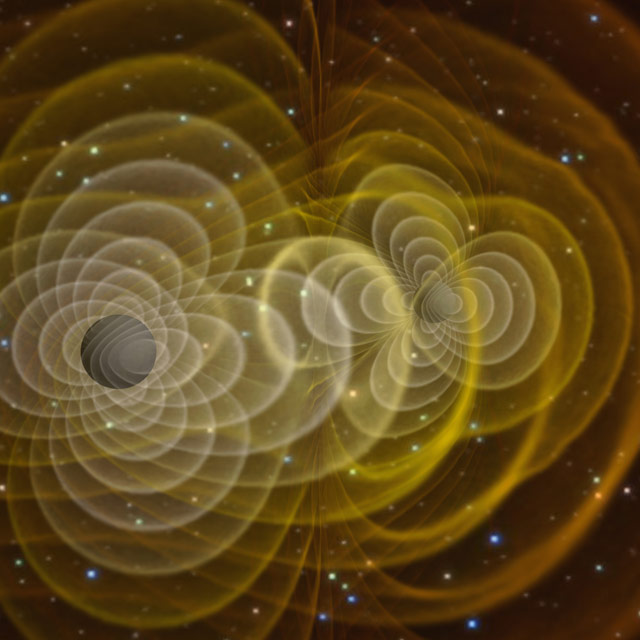

Gravity is the consequence of masses such as planets warping the fabric of space and time around them, according to Einstein's theory of general relativity. When massive bodies such as stars and black holes move, they are predicted to radiate ripples in space-time called gravitational waves. [The Search for Gravitational Waves (Gallery)]

When a gravitational wave passes through an object, it should trigger very small but potentially detectable vibrations. Gravitational wave detectors range from instruments that can fit on desks to devices that are miles long. However, so far no one has reported directly detecting a gravitational wave.

Scientists reasoned that Earth itself could be used as a gravitational wave detector. One might potentially detect the combined effects of gravitational waves streaming through the planet by analyzing its seismic activity — that is, how much Earth shakes.

In the new study, researchers focused on gravitational waves with frequencies of 0.05 to 1 hertz, a band largely overlooked by other detection efforts. Potential emitters in this range include pairs of cosmic objects such as white dwarfs, neutron stars and black holes as they orbit each other. Gravitational waves with such frequencies also may be given off by rapidly spinning neutron stars known as pulsars.

The scientists employed supercomputers to comb through a year's worth of publicly available data from a global network of 40 seismometers normally used to study earthquakes and the internal structure of the Earth. They did not detect the effects of gravitational waves per se, but they set a new upper limit for the amount of energy the planet might receive from gravitational waves of these frequencies. This upper bound improves by a factor of a billion the limits set by previous lab experiments, researchers said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers intend to carry out a similar analysis using seismometers that NASA's Apollo missions placed on the moon. These could provide even better data than instruments on Earth because the moon is far less seismically active than Earth, lead study author Michael Coughlin, a physicist at Harvard University, told Space.com.

Coughlin and his colleague Jan Harms detailed their findings online March 13 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us