Sun's Magnetic Field Will Flip Soon (Video)

The sun's polarity is getting closer to flipping. The star's northern hemisphere's polarity has already reversed, and the southern hemisphere should follow suit soon, scientists say.

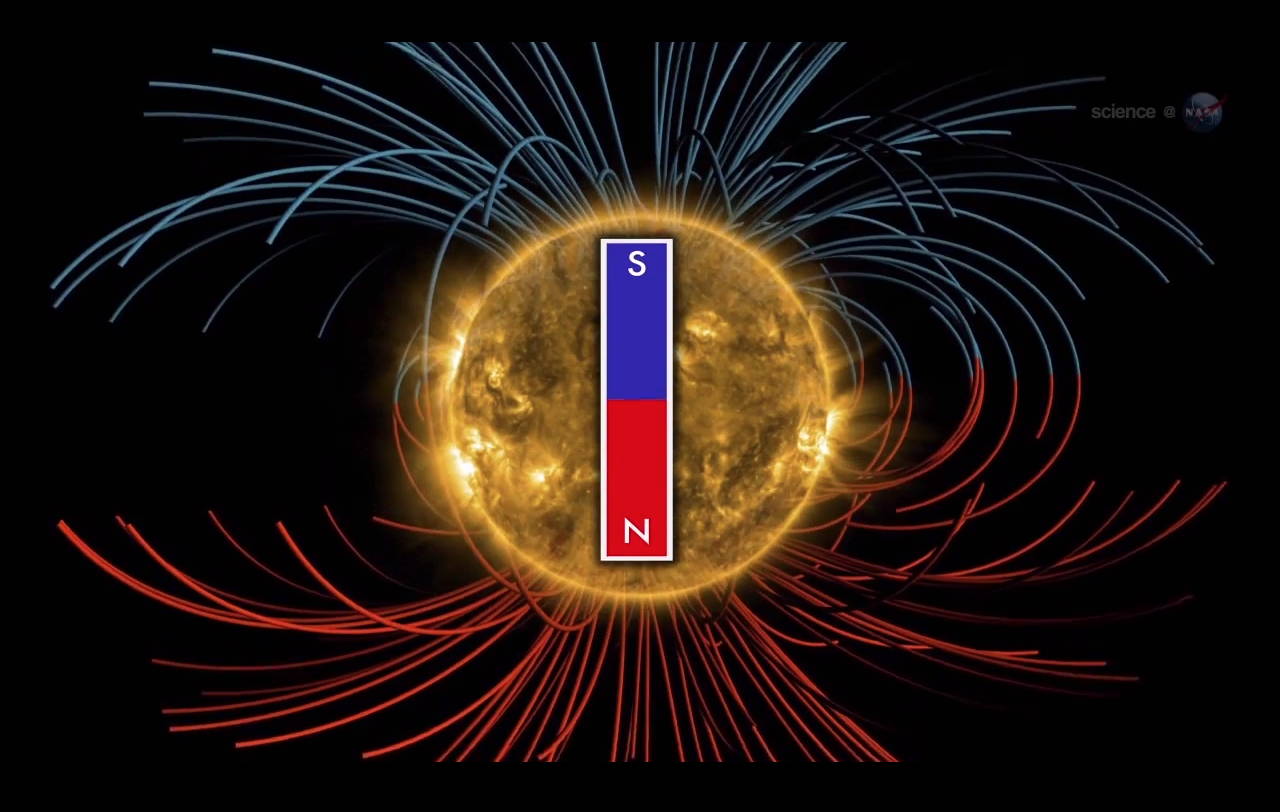

Every 11 years or so, the two hemispheres of the sun reverse their polarity, creating a ripple effect that can be felt throughout the far reaches of the solar system. The sun is currently going through one of those flips in its cycle, said scientists working at Stanford University's Wilcox Solar Observatory, which has monitored the sun's magnetic field since 1975.

"The sun's poles are reversing, and this is a large-scale process that takes place over a few months, but it happens once every 11 years," Todd Hoeksema, a solar physicist at Stanford said in a video about the polarity reversal. "What we're looking at is really a reversal of the whole heliosphere, everything from the sun out past the planets."

The polarity reversal builds up over time. A sunspot spreads out, causing the sun's magnetic field to migrate from the equator of the star to one of the sun's poles. As this change occurs, the sun's magnetic field reduces to zero and then comes back with the opposite polarity, Hoeksema said in a statement. [Solar Max: Photos of the Active Sun in 2013]

"When that reverses it effects us here on Earth because not only do we see more cosmic rays, but there's also more activity on the sun," Hoeksema said. "That activity comes in and it affects the Earth's magnetic field."

The planet's magnetic field affects technology on Earth like GPS systems and power grids, Hoeksema said. The uptick in solar activity can also create brilliant auroras on Earth and on certain planets of the solar system.

"We also see the effects of this on other planets," Hoeksema said in a statement. "Jupiter has storms, Saturn has auroras, and this is all driven by activity of the sun."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

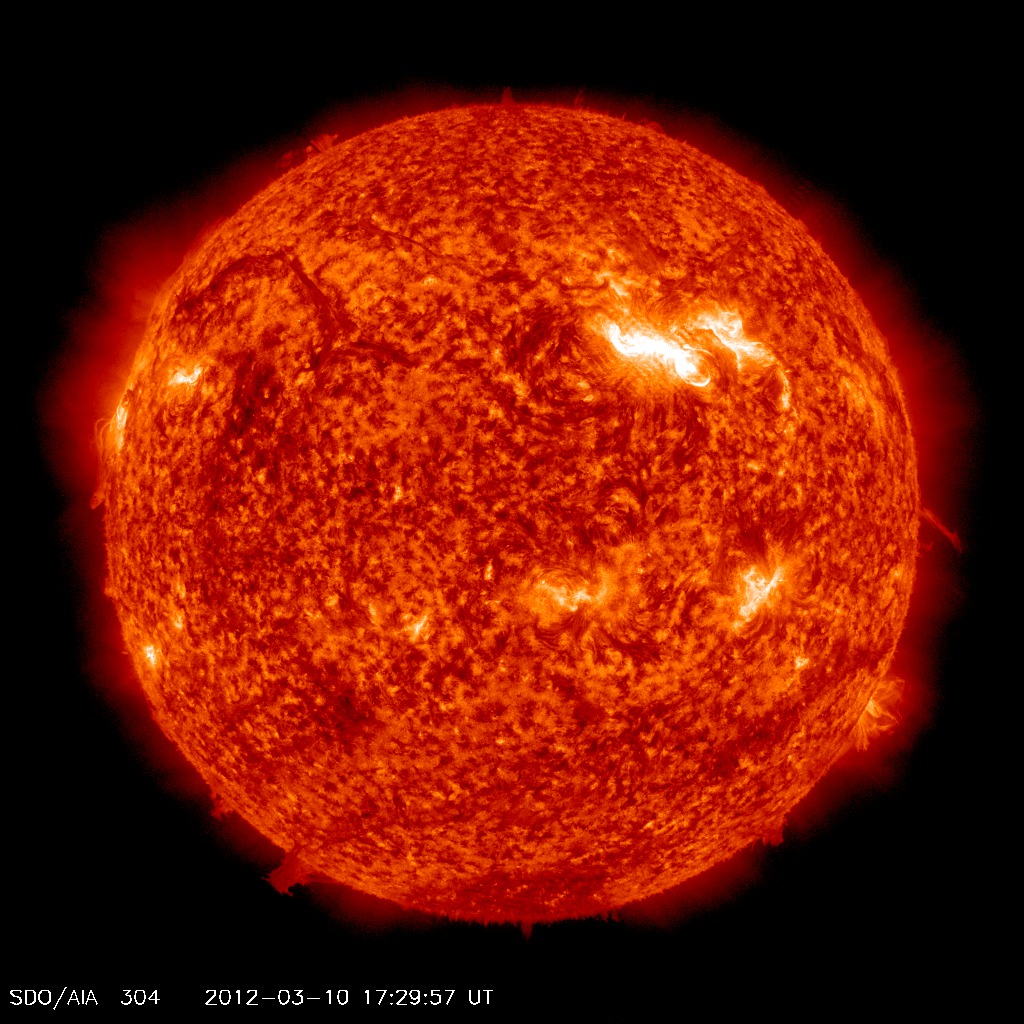

This part of the sun's cycle is known as the "solar maximum." The solar max marks the peak in the star's activity. Usually, the sun's polarity reversal happens during this period of the solar cycle, however, the reversal isn't responsible for the increased number of solar flares and eruptions known as coronal mass ejections usually observed around solar max.

The increased activity acts as an indicator that the polarity reversal will occur, but it doesn't cause the sun to become more active, Hoeksema said in an earlier interview with SPACE.com.

The polarity reversal probably won't harmfully impact Earth, in fact, it could even protect the planet in some ways, scientists have said.

The sun's huge "current sheet" — a surface extending out from the sun's equator — becomes wavier as the poles reverse. The sheet's crinkles can create a better barrier against the cosmic rays that can damage satellites, other spacecraft and people in orbit, scientists said.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.