NASA to Launch New Sun-Watching Satellite This Month

A new NASA spacecraft is weeks away from launching into orbit to study a region of the sun that will help scientists better understand how the solar atmosphere works, scientists said today (June 4).

The Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) probe is slated to launch on June 26 from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. The satellite will be carried aboard an Orbital Sciences Pegasus XL rocket, which will be released from the company's L-1011 aircraft at an altitude of 39,000 feet (about 12,000 meters).

IRIS will study the sun's lower atmosphere, which is an area known as the "interface region." The satellite is expected to provide the most detailed look at this part of the solar atmosphere, which has been largely unexplored until now, said Jeffrey Newmark, an IRIS program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

"IRIS will fill crucial gaps in our understanding of the role the interface region plays in powering its million-degree atmosphere, called the corona," Newmark told reporters in a news briefing today. [Infographic: How the Tiny IRIS Sun Observing Satellite Works]

The sun's atmosphere

The sun's interface region, where most of the star's ultraviolet emissions are generated, is located between the sun's visible surfaceand its upper atmosphere. Activity in this area powers the sun's atmosphere and drives solar wind, said Alan Title, principal investigator of the IRIS mission at Lockheed Martin's Advanced Technology Center in Palo Alto, Calif.

Temperatures in the interface region reach approximately 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (more than 5,500 degrees Celsius), and IRIS will examine how solar material moves, gathers energy and heats up as it travels through this part of the lower atmosphere.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Immediately above [the interface region], temperatures rise to a million degrees in the corona, but how that happens is a mystery," Title said. "What are the processes that occur there?"

Previous solar observations have suggested that massive structures in the lower atmosphere help funnel energy into the sun's upper atmosphere. These jet-like features, which occupy an area roughly the size of Los Angeles, can stretch up to 100,000 miles (161,000 kilometers) long and travel at a blistering pace of 360,000 miles per hour (579,000 km/h), Title said.

IRIS will be able to observe these structures in unprecedented detail, including gathering information about the structures' velocity, temperature and density, Title said.

"What we want to discover is what the basic physical processes are to transfer energy and material from the surface of the sun out to the outer atmosphere, to the corona," he said.

Satellite specs

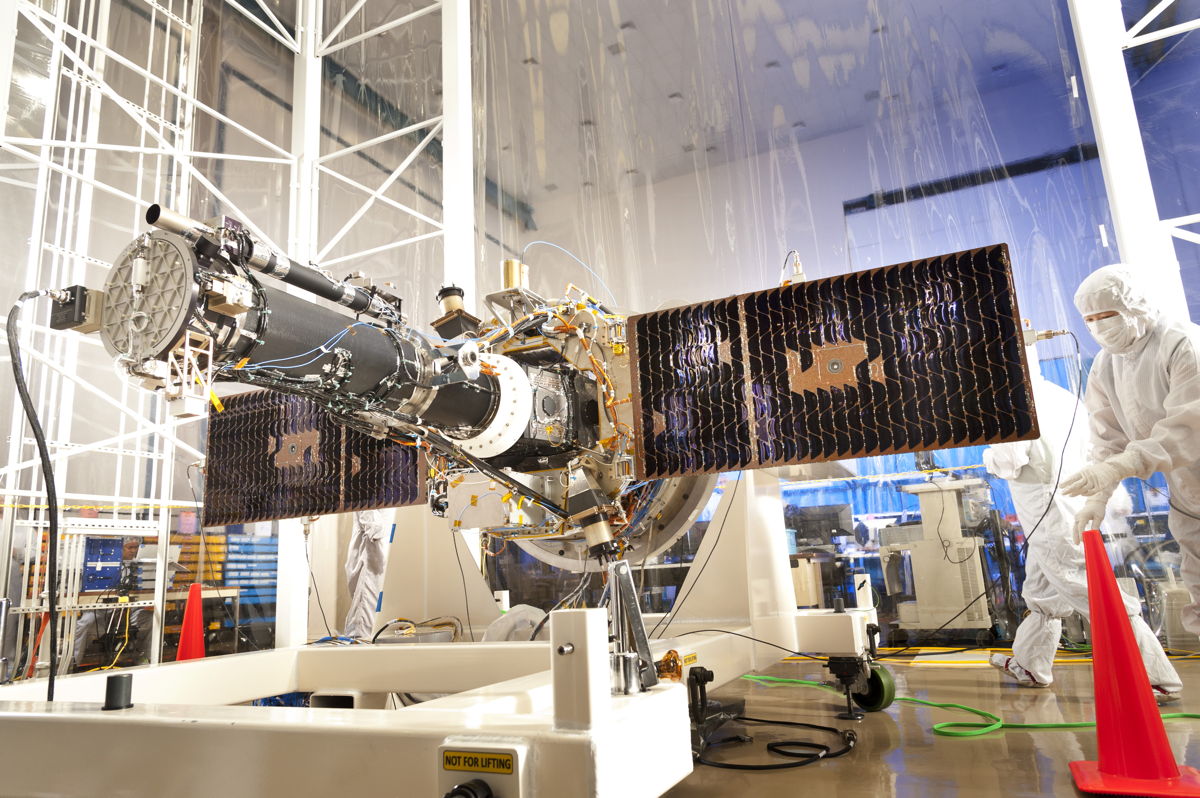

IRIS is equipped with an ultraviolet telescope that is designed to take high-resolution images every few seconds and provide observations of areas as small as 150 miles (241 km) on the sun, according to NASA officials.

The satellite will circle Earth in a sun-synchronous polar orbit, which means it will fly along the planet's dawn/dusk line, looking toward the sun, said John Marmie, IRIS assistant project manager at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif.

Each orbit will take 97 minutes to complete, which will allow IRIS to circle the planet about 14 or 15 times each day, from an altitude of about 373 miles (600 km). This path, which is designed to take the spacecraft over the equator at the same local time every day, allows for nearly continuous looks at the sun, mission planners said.

After IRIS reaches orbit, mission managers will spend about a month checking the onboard instruments before the satellite officially begins collecting scientific data.

The IRIS probe weighs 400 pounds (181 kilograms), and measures 12 feet across (3.7 meters) with its solar panels fully extended.

The $181 million mission is designed to operate for about two years, but mission planners say IRIS could operate for much longer, since the satellite will not be carrying any fuel or other consumable materials.

"If, after two years, the observatory is healthy and productive, NASA has the option to extend operations," Title said.

When launched, IRIS will join a fleet of sun-watching spacecraft operated by NASA and its partner agencies, including the Solar Dynamics Observatory and the Hinode probe.

"Together they will explore how the solar atmosphere works, and how it impacts Earth," Newmark said.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.