40 Years Later, NASA's Pioneer 11 Probe's Solar System Legacy Lives On

On April 5, 1973, exactly 40 years ago, Pioneer 11 blasted off from Cape Canaveral for a risky mission that would take the small satellite dangerously close to Jupiter's surface and through Saturn's outer rings, paving the way even more ambitious explorations of the solar system.

The spacecraft had a tough act to follow. Its sister craft, Pioneer 10, which launched on March 2, 1972, was the first to fly beyond Mars, the first to fly through the asteroid belt and the first to zip by Jupiter, sending volumes of scientific data back to Earth.

But Pioneer 10's success allowed NASA managers to set their sights higher for the 9.5-foot (2.8-m), 570-pound (258-kg) Pioneer 11. The spacecraft would fly not only three times closer to Jupiter than Pioneer 10 but it would also whiz past the next planet out: Saturn.

Pioneer 11 made its closest approach to Jupiter on Dec. 3, 1974, at just 27,000 miles (43,000 km) from the gas giant's atmosphere, flying over the planet's poles to avoid the intense radiation belts around the Jupiter's equator. The planet's massive gravitational pull was used as a slingshot to send Pioneer 11 hurtling toward Saturn.

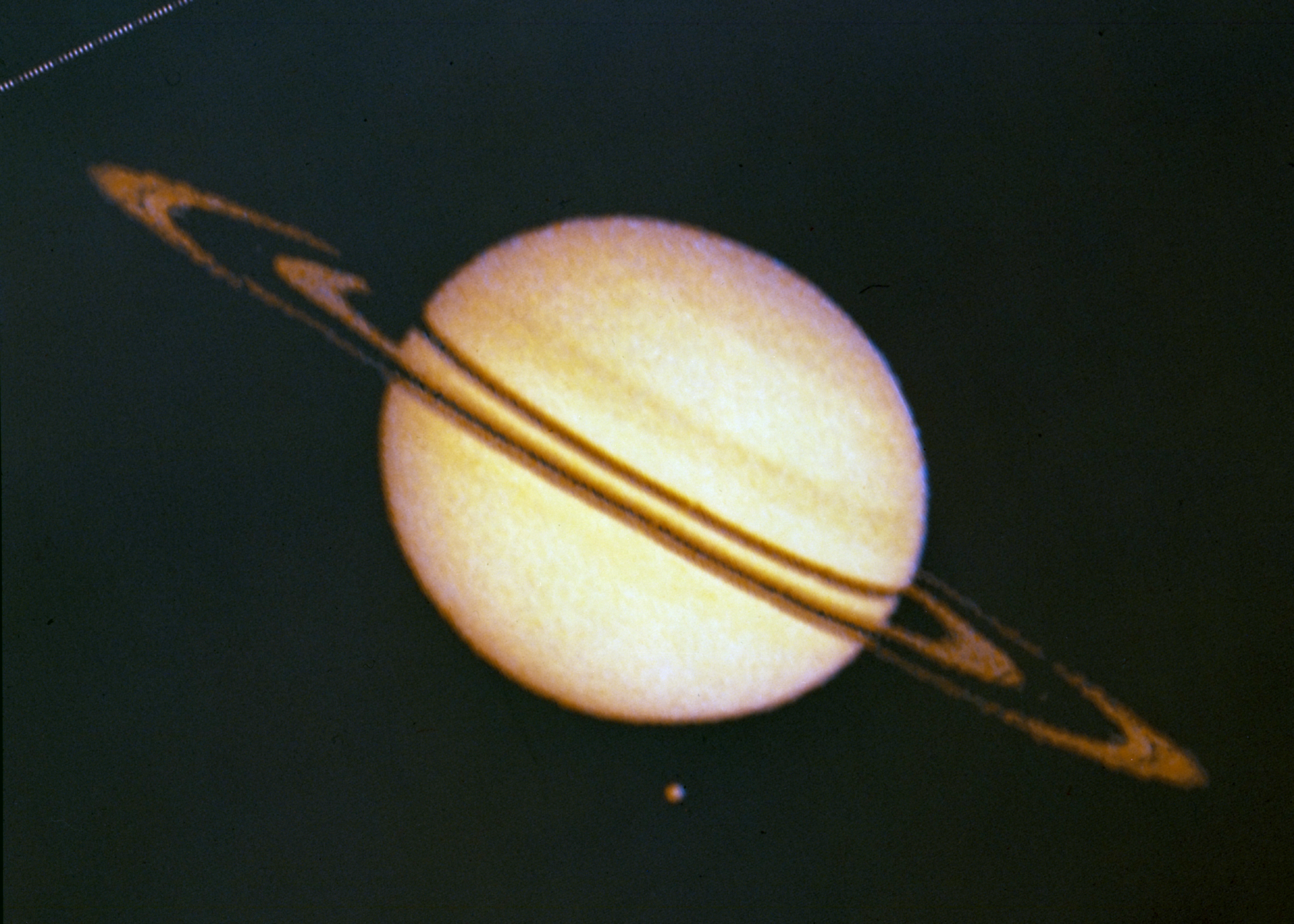

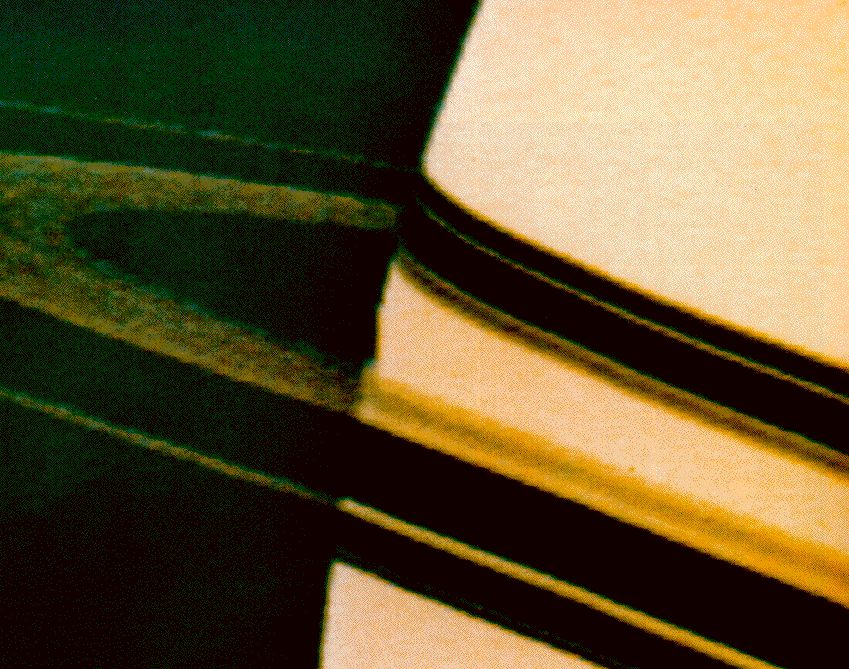

The Pioneer team originally wanted to send the spacecraft through Saturn's elusive inner rings, but NASA decided to have it take a less risky path through Saturn's outer A ring, in order to test a critical part of the route Voyager 2 would take on its "Grand Tour" of the solar system. Managers at the space agency reasoned that Voyager 2's safe passage to Uranus and Neptune would be more important for science than a Pioneer journey through the inner rings of Saturn.

"It was a controversial decision at the time," Pioneer's last project manager, Larry Lasher, said in a statement NASA released today to mark the mission's 40th anniversary. "But with the brave path it forged, Pioneer 11 was proud to contribute to the success of Voyager 2 in its completion of the 'Grand Tour,' and the exploration of two of the outermost planets in our Solar System."

This safer route still allowed Pioneer 11 to capture amazing images of Saturn, and it even discovered a couple of previously unknown small moons around the planet, and a new ring, dubbed the F ring.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The last transmission from Pioneer 11 was received in 1995. According to NASA, the spacecraft is now thought to be 8 billion miles (13 billion km) from the sun and traveling in the direction of the constellation Scutum.

Should they ever be intercepted by extraterrestrials, Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 both carry gold plaques to describe where the spacecraft came from, with images of an unclothed man and unclothed woman, a diagram of a solar system and a pictorial showing the sun relative to other nearby stars. The plaque was co-designed by SETI founder Frank Drake and television host and astronomer Carl Sagan.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.