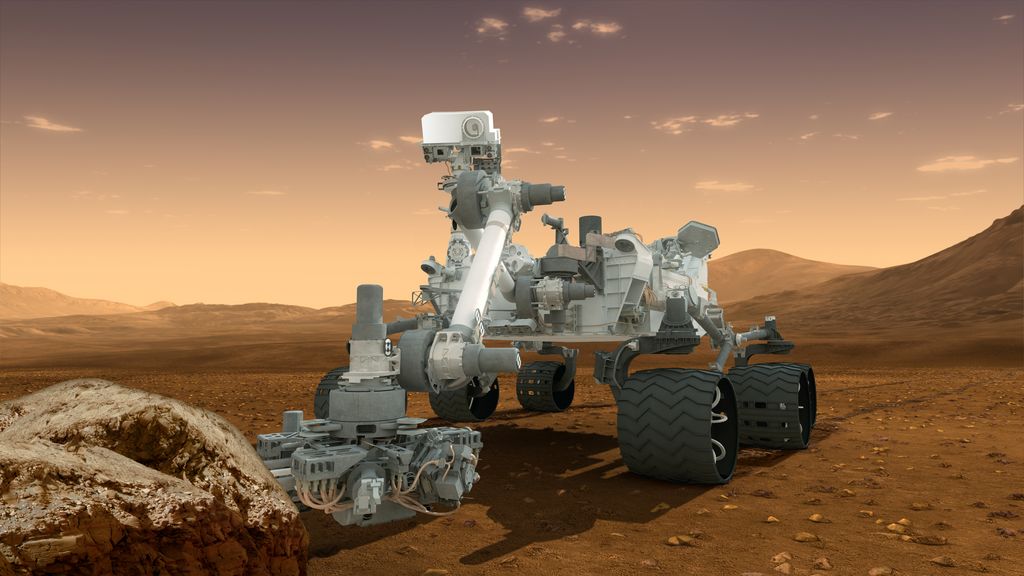

How NASA's New Mars Rover Will Phone Home

After NASA's Curiosity rover lands on Mars this weekend, one of its first orders of business will be to call home.

Mission managers back on Earth will be eagerly awaiting news of the $2.5 billion Mars Science Laboratory rover, which is due to land at 10:30 p.m. PDT on Aug. 5 (1:30 a.m. EDT, 0530 GMT, Aug. 6), beginning a two-year mission. In fact, for the first 90 days of the mission, controllers will work together as if each day were 24 hours and 40 minutes long — the approximate length of a Martian day.

"It's to get the most use possible for the rover while it's fresh and new on Mars," says Ashwin Vasavada, MSL's deputy project scientist. "Ideally, we'd do it for the next 10 years, but the reality is, after 90 days it's better for everyone to go back to Earth time."

Controllers on Earth will have three ways of hailing Curiosity as it trundles around Gale Crater. Two are direct links through NASA's Deep Space Network, a worldwide collection of antennas. It provides both a fixed low-gain antenna, best for basic commands and emergencies, and a pointable high-gain antenna for complex commands. [11 Amazing Things NASA's Mars Rover Can Do]

Curiosity also has a higher-speed ultra-high frequency (UHF) communications system that can send signals to spacecraft orbiting Mars, which in turn would relay them to Earth.

To send back imagery, Curiosity must stay in touch with the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Mars Odyssey spacecraft, two probes orbiting Mars that each can talk to the rover twice a day. (Odyssey is currently recovering from the loss of one of its three reaction wheels.)

"The high-gain antenna only gives us a moderate amount of bandwidth," Vasavada told SPACE.com. "We can transmit a series of commands every morning. But it's not enough to transmit hundreds of images every day."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For navigation purposes, the rover has two guidance systems on board. One keeps the rover apprised of its position on the Red Planet, which is needed to find Earth in the sky and keep in contact with NASA. The other system calculates how close Curiosity is to rocks and other obstacles.

"For that system, we don't care exactly where we are in the universe," Vasavada said. "We care about it if we can shoot at this rock with our laser or not."

For measuring the distance to rocks and other objects, Curiosity will use several cameras to create stereo range maps and gain a three-dimensional view of its surroundings.

Controllers then must decide how Curiosity will guide itself to the target. It can use a "blind" mode, where it is told to drive a certain distance in one direction, or it can switch to a hazard-avoidance situation, in which the rover frequently checks the environment to make sure it can move safely.

Curiosity has sensors to sense if it's slipping, and it will stop movement immediately if it drops beyond a certain threshold. A previous rover, Spirit, ended its journey in a sand trap, but Vasavada says Curiosity's slip-avoidance system was not necessarily included in response to Spirit's fate.

"You just have to make a risk assessment before you send the command," he says. "Spirit's problem was it was a layered surface. What was on the surface tricked everyone involved into thinking it was safe to drive on, and then it punched through that layer."

With Curiosity, "we're going to be very careful and have this group of scientists and engineers work together every time we command a drive."

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.