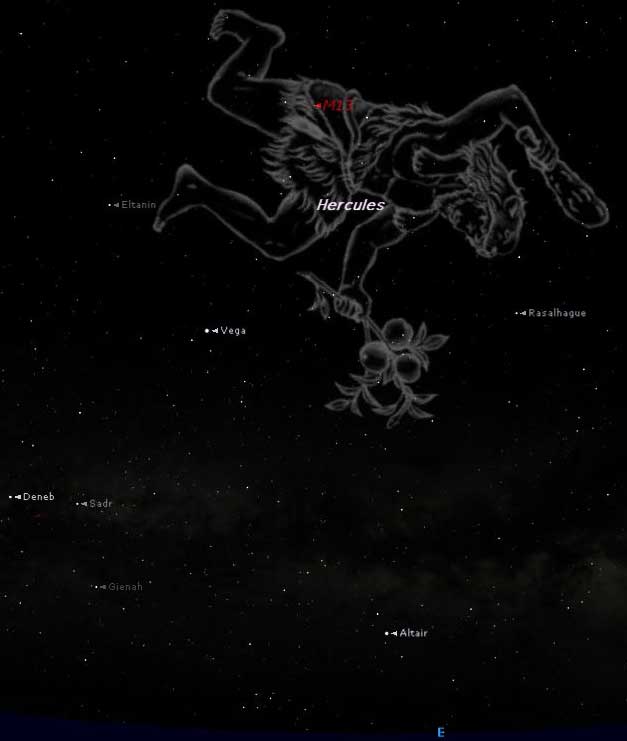

Hercules Constellation Now Showing in Summer Night Sky

With the bright moon out of the late evening sky early this week, stargazers will be treated to views of the "celestial strongman" in the night sky: the constellation of Hercules.

To spot the constellation of Hercules, look high overhead at around 10 p.m. local time. The star pattern of the traditional mythological figure is difficult for modern skywatchers to visualize, but astronomer Robert H. Baker (1880-1962) described its six brightest stars as a "butterfly with outspread wings." Others sometimes describe those same stars as outlining the initial "H" for Hercules.

In ancient times, however, primitive men seemed to have no difficulty picturing these stars as forming the figure of a kneeling man.

In about 260 B.C., the Greek poet Aratus noted that "... no one knows how to read that sign clearly, nor on what task he is bent."

Strongman or danceman?

Aratus referred to Hercules as a "phantom," and pointed out that Hermes brought a Lyre into heaven (the nearby constellation of Lyra) and set it in front of the unknown phantom near his left hand.

Lyra was known to the Greeks as the first string instrument of their bards. In fact, the Arabs called the kneeling phantom, "Al Rakis, the Dancer," and also the "One Who Kneels On Both Knees." The old Arabic name of its brightest star, Ras Algethi, means "The Head of the Kneeler."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The poets from 22 centuries ago were actually singers and dancers — the early bards danced and sang, accompanying themselves on the harp with appropriate music. Some experts in mythology believe that the constellation we now call Hercules may have originally represented Thamyris, a son of the king Philammon whose main avocation was to sing, dance and play the harp. [Skywatching Maps & Charts]

So, exactly who are these stars supposed to represent? Was it really Hercules, the half-mortal son of Zeus who was immensely strong and revered throughout the Mediterranean? Or perhaps it was Thamyris, who otherwise might have become known as the celestial song and dance man of the sky?

The Great Cluster in Hercules

Within Hercules is quite possibly the most celebrated object in the summertime skies: The Great Cluster in Hercules, which is also known as M13. The M represents the initial of the famed 18th century comet observer, Charles Messier (1730-1817).

Messier was deeply interested in discovering comets but he was plagued by the same trouble that besets all comet hunters: he kept finding "comets" that were not comets at all, but star clusters and nebulas. Messier's hopes were dashed so often that for his own convenience, he kept a list of these deceiving objects, which he published in a catalogue.

To locate Messier 13, look toward the four stars, known as the "Keystone," which supposedly forms the body of Hercules. A keystone is the stone atop an arch, and its shape is narrower at one end.

It is between the two western stars of the keystone that we can find the Great Globular Cluster of Hercules. It’s about a third of the way along a line drawn from the stars Eta to Zeta.

Actually, it was not Messier, but Edmund Halley (who discovered the famous comet of the same name), who first mentioned it in 1715, having discovered it the previous year: "This is but a little Patch," he wrote, "but it shows itself to the naked Eye, when the Sky is serene and the Moon absent."

A celestial chrysanthemum

Located about 25,000 light-years away, the Hercules Cluster measures 160 light-years across, and is estimated to be made up of a ball of tens of thousands of stars.

Messier first saw the cluster in June 1764 and described it as a "round and brilliant nebula with a brighter center, which I am sure contains no stars."

Today, if you use good binoculars and look toward that spot in the sky where M13 is located, you will likely see a similar view: a vaguely round glow or patch of light.

Moving up to a telescope, the view dramatically improves. With a 4- to 6-inch telescope, the "patch" starts to become resolved into hundreds of tiny pinpoints of light. In larger instruments, Messier 13 is transformed into a spectacular celestial chrysanthemum.

In his Celestial Handbook, Robert Burnham (1931-1993) describes the view of the cluster in a 12-inch or larger telescope as, "... an incredibly wonderful sight; the vast swarm of thousands of glittering stars, when seen for the first time or the hundredth, is an absolutely amazing spectacle."

Editor's note: If you have an amazing skywatching photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.