Solar Storm Warning System May Predict Dangerous Radiation

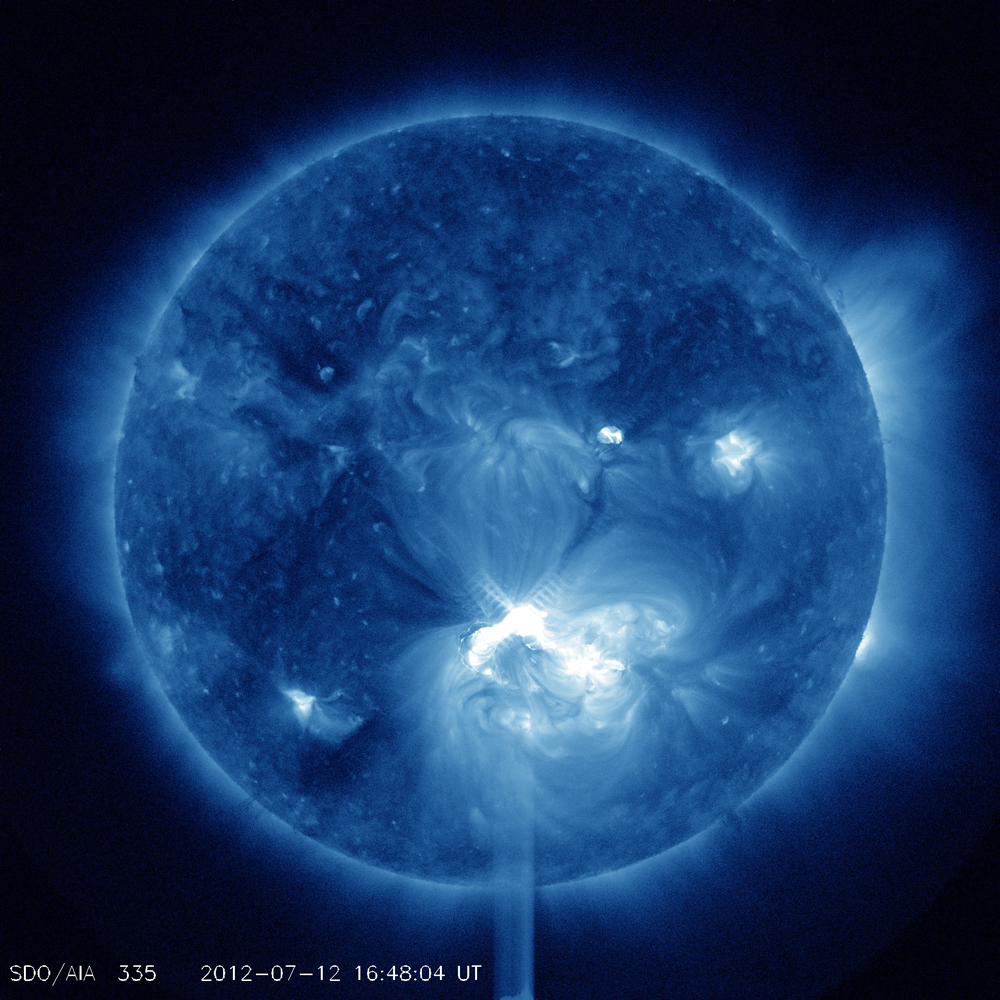

A new warning system that measures high-energy particles spewed from the sun during powerful solar storms may help scientists forecast the intensity of potentially harmful radiation when these solar tempests are aimed directly at Earth.

The warning system was developed by physicists at the University of Delaware in the U.S. and the Chungnam National University and Hanyang University in South Korea. For certain radiation levels, the system is designed to predict when incoming charged particles will be at their strongest point.

In some cases at lower energies, measurements from the space weather warning system may provide up to 166 minutes, or nearly three hours, of advance notice.

Solar eruptions unleash plasma and charged particles into space that can pose radiation hazards to satellites in orbit, astronauts in space and electronics infrastructure on Earth. Depending on the strength of the storm, these outbursts can cause radio blackouts, disrupt power grids and pose health risks to spaceflyers. During solar storms, airlines often reroute planes that would normally fly over Earth's polar regions as a precautionary measure.

"If you're in a plane flying over the poles, there is an increased radiation exposure comparable to having an extra chest X-ray you weren't planning on," study co-author John Bieber, of the University of Delaware's Bartol Research Institute, said in a statement. "However, if you're an astronaut on the way to the moon or Mars, it's a big problem. It could kill you."

Space weather prediction

With the sun's activity ramping up toward an expected peak next year, being able to forecast these storms could prove to be a highly useful tool. As NASA plans future missions beyond low-Earth orbit — to an asteroid, the moon or Mars — it will also be crucial for solar physicists to be able to determine when solar storms pose health threats for astronauts.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Traveling nearly at the speed of light, it takes just 10 minutes for the first particles ejected from a solar storm to reach Earth," Bieber said.

To develop the warning system, the researchers analyzed data collected by two neutron monitors at the South Pole — one inside and one outside of the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. These instruments measured the intensity of the high-energy, fast-moving particles that first arrive at Earth from solar eruptions.

Studying these particles that reach Earth first helps the scientists estimate when slower-moving but more dangerous particles will follow.

"These slower-moving particles are more dangerous because there are so many more of them," Bieber said. "That's where the danger lies."

Since the particles are less energetic, the radiation is also more likely to affect humans, such as astronauts on space missions.

"The lower-energy protons are sufficiently slow that we slow them down and stop them with our bodies, so they do more damage," said Joseph Kunches, a scientist at the Space Weather Prediction Center, which is jointly managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Weather Service.

The Space Weather Prediction Center monitors solar activity and assesses the potential impact of solar storms.

"Generally speaking, if they're slower, they'll deposit all of the energy into your body because they're not fast enough to fly right through," Kunches told SPACE.com.

Measuring radiation from the sun

To test the accuracy of their warning system, the researchers matched their calculations for 12 solar storms to observations made by geosynchronous satellites, and found comparable results for charged particles with energies higher than 40 million to 80 million (or megaelectron) volts.

According to Kunches, the new system is particularly useful to protect astronauts on future missions beyond low-Earth orbit, but the energy levels measured are still too low.

"The energy that they focus on is like the energy that would be a serious issue if you were going to go to Mars and go back to the moon," Kunches explained. "As you go to higher energies, your lead time is diminished."

Still, Kunches said the system represents an incremental improvement in space weather forecasting.

"It's valuable, but I think it's valuable for really educated users who know exactly what energies may be problematic for them," Kunches said.

Details of the warning system are reported in the journal Space Weather: The International Journal of Research and Applications, which is published by the American Geophysical Union.

The research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea through the South Korean government and by the U.S. National Science Foundation and NASA.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.