Comet's Death Dive Into Sun Seen in Detail for 1st Time

A comet has been spotted disintegrating in the atmosphere of the sun for the first time.

Such sun-diving comets are common but none have been seen surviving entry into the sun's atmosphere until now. They could help reveal what comets are made of and also uncover hidden properties of the sun's atmosphere, researchers said today (Jan. 19) as they announced the discovery.

A group of comets known as the Kreutz family regularly flies perilously close to the sun.

In the past 15 years, more than 1,400 of these dirty snowballs have been detected, likely originating from a giant parent comet 20 to 100 kilometers wide (12 to 62 miles) that broke apart as recently as 2,500 years ago. However, until now, none of the telescopes trained on the sun was sensitive enough to follow any of these comets to their demise in the sun's atmosphere.

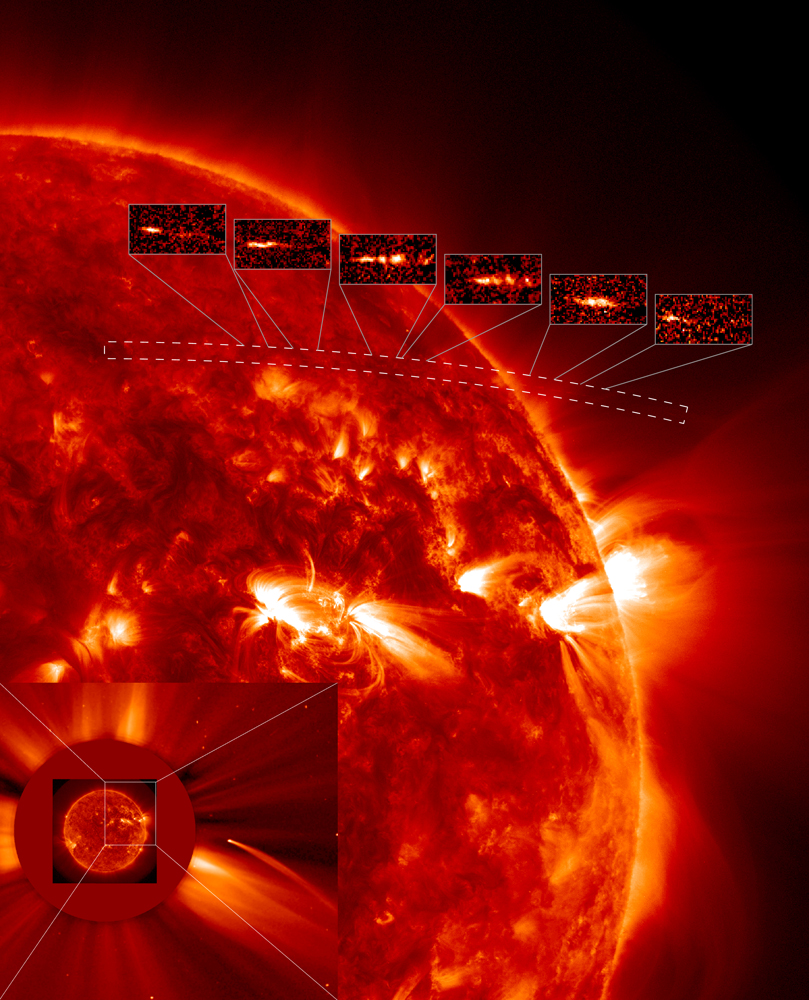

Using NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), Solar Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) and Solar-Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO), scientists followed the Kreutz comet C/2011 N3 in its mad dash to the sun. [Photos of Death-Defying Comet Lovejoy]

"It was very surprising to see this comet at all," Karel Schrijver, an astrophysicist at Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center in Palo Alto, Calif., told SPACE.com. "We may think that an object of some 60,000 metric tons and some 50 meters [164 feet] across is large and heavy, but if you compare it to the sun, which can easily hold a million Earths, it is astonishing that such a small object glows brightly enough to be seen."

Schrijver is the lead author of the study of the disintegrating comet. The scientists detail their findings in the Jan. 20 issue of the journal Science.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Doomed comet's death dive

Researchers first detected the comet last July 4, two days before its destruction. It initially had a tail more than 6,200 miles (10,000 kilometers) long and was diving at the sun at about 1.3 million mph (2.1 million kilometers per hour). During the final 10 minutes of observations, the comet lost about 1.5 million to 150 million pounds (700,000 to 70 million kilograms).

"We've been able to bracket its size as between 30 and 150 feet (9 and 45 meters) long, with a greater likelihood that it lies at the upper end of that range," Schrijver said. "And it most likely weighed in at as much as 70,000 tons, giving it about the weight of an aircraft carrier when it first became visible."

On July 6, the comet managed to reach deep into the sun's atmosphere, about 62,000 miles (100,000 km) from the surface. As it approached that point, it broke up into many large pieces ranging in size from dust up to about 150 feet (45 meters) wide. Then it completely vaporized.

A glimpse inside comets

As sun-diving comets disintegrate, they could reveal much about how comets in general are put together and what their components are scientists say. Since comets date back to the origins of the solar system, such details about their death throes could lead to a better understanding of how the planets evolved from protoplanetary gas and dust.

The behavior of these comets as they graze the sun also could shed light on the sun's mysterious high-altitude atmosphere. Scientists normally are unable to see this part of the sun because its glow is not bright enough for telescopes, while it is still too close to the sun to observe with instruments that block out the bright disk of the sun, Schrijver said.

Understanding how the sun's atmosphere works could in turn reveal more about the operations of the sun's roiling surface, which can often burst with solar flares that affect Earth.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us