Milky Way's Baby Stars Linked to Stellar Growth Spurt

Star formation in the center of the Milky Way underwent a growth spurt approximately 25 million years ago.

After a slow period, the mass of baby stars that were created more than tripled, according to new research. Such a peak could indicate an influx of gas into the galactic bulge.

To figure out star birth rates, an accurate count of the ages of stars in the area first had to be determined.

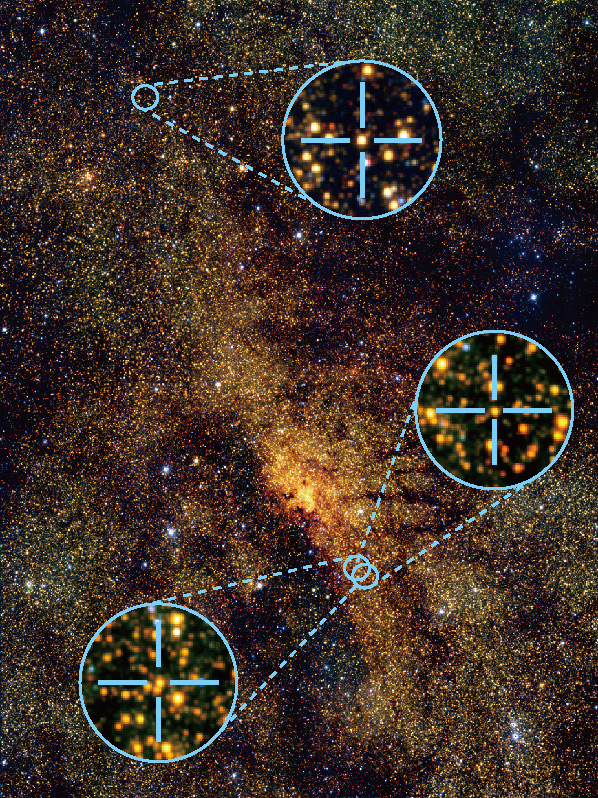

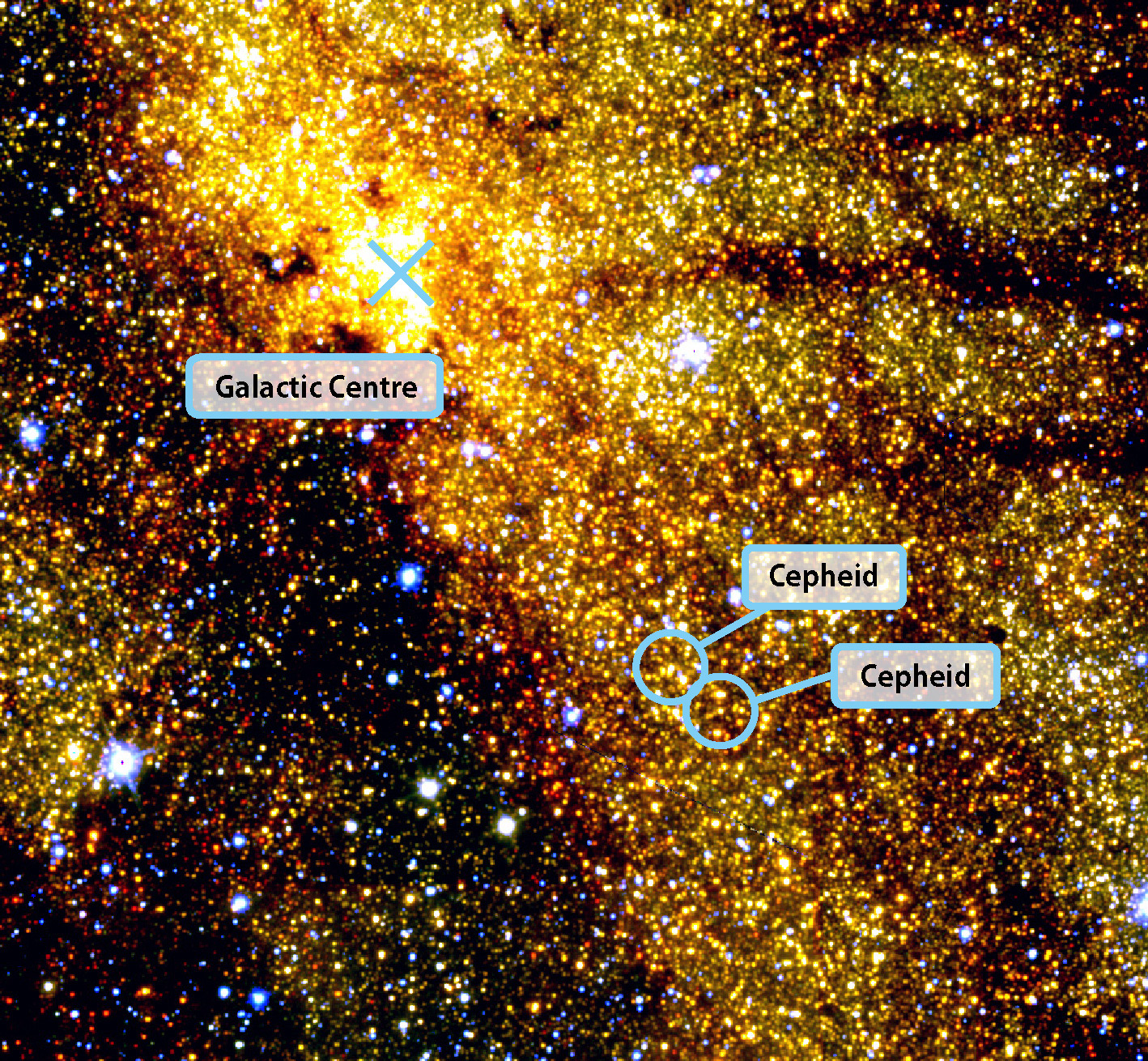

An international team of astronomers turned the Infrared Survey Facility at the South African Astronomical Observatory toward the center of the galaxy in search of a special kind of pulsing star known as Cepheid variables. [Top 10 Star Mysteries]

"It is difficult to determine the ages of stars unless they have some special characteristic," primary author Noriyuki Matsunaga, of the University of Tokyo, told SPACE.com via email.

Counting stars

The steady strobe of Cepheids is related to their age. As they grow older, they flash faster and faster, allowing astronomers to determine just how long they've been around.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It takes stars approximately 10 million years to develop the pulse Cepheids are known for. The stars can last up to 200 million years before dying. This should have provided astronomers with a range of stars to study.

But oddly enough, the only Cepheids the astronomers located were all between 20 million and 30 million years old.

Matsunaga explained that the probability of seeing younger Cepheids was low. Because a star takes around 10 million years to evolve into a variable, it was possible that none of the stars within the field of view would have spent only 10 million years — a brief span of time, astronomically — as a Cepheid.

"On the other hand, the probability to see the older Cepheids is higher," Matsunaga said. "If stars 30 [million] to 70 million years old existed, we should have detected several." [Biggest Revelations of the Space Age]

Instead, they saw none.

"The absence of the shorter-period Cepheids was unexpected," Matsunaga said.

Stellar birth rates

Calculating star formation rates is an exercise in probability. Astronomers know how likely a Cepheid is to form, versus other, nonpulsing stars. The team took the three Cepheids they found and worked backward to determine star formation rates during the two periods.

When these three pulsing stars formed, the bulge of the Milky Way was churning out approximately 0.075 solar masses per year.

The lack of older pulsing stars implied that, overall, less stars were forming 30 million to 70 million years ago. If more stars were created, then more Cepheids would have been seen. Matsunaga's calculations put the rate of star formation at 0.02 solar masses a year.

"Stars are formed more actively in a region with more massive and more dense gas," Matsunaga said.

"Therefore, the change in star formation rate suggests that the gas density in the bulge was higher 25 million years ago."

He went on to explain that other research reveals that different formations within a galaxy could lead to random inflows of gas, which would fuel star formation.

Such an inflow seems to have occurred 20 million to 30 million years ago, bolstering the rate at which stars are created.

Understanding these inflows provides astronomers with a better idea of how the Milky Way evolved, and what it may do in the future.

The paper was published in the Aug. 24 issue of the journal Nature.

Visit SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky