How We Snapped a Picture-Perfect Space Shuttle Launch: A Photography Team's Triumph

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. ? "T minus 10 . . . 9 . . . 8 . . . 7 . . . 6 . . . 5 . . . 4 . . . All three engines up and burning . . . 2 . . 1 . . . Zero and liftoff, the final liftoff of Atlantis."

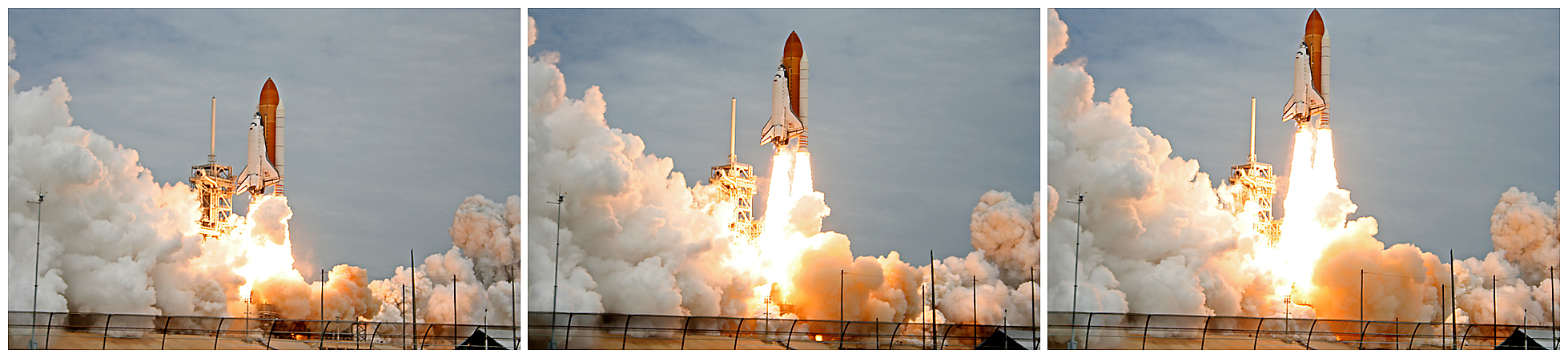

Those were the words hundreds of thousands of people gathered at NASA's Kennedy Space Center had been waiting to hear. The spectacular fiery ascent of the space shuttle Atlantis and her crew into orbit and into history was the happy culmination of a week filled with tension and anxiety.

And for the hundreds of media photographers and videographers like us who had set up remote cameras around the launch pad to capture this historic flight, the effort was well worth the rain, heat, humidity and nasty mosquitoes. Months of preparations paid off, and many came away with stunning images of Atlantis breaking the bonds of Earth's gravity. [Photos of NASA's Last Space Shuttle Launch]

It's now or never

We had watched four shuttle landings at Edwards Air Force Base in California back in the late 1980s, but we had never seen or experienced a shuttle launch.

The closest we came was last November, during Discovery's STS-133 mission. We stayed for a week in Florida, but a series of weather and technical problems kept delaying liftoff until ground controllers finally decided to move the launch date to February. We were heartbroken, especially after driving more than 1,500 miles from Boston in 24 hours.

So we decided we would fly down to Kennedy Space Center for STS-135. We told ourselves: It's now or never!

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Adventures with the remote camera

We have led and/or organized eight successful expeditions to observe total eclipses of the sun from Asia, North America, the Caribbean, Europe, Africa and the Pacific. The level of detail needed to prepare for a shuttle launch was no different.

We had a checklist to make sure we didn't leave behind any critical adapter, cable or screw that would jeopardize our objective, and we had to practice our technique with our setups to make sure we could track Atlantis smoothly as it cleared the tower. (Our years of shooting military jets at air shows really helped.)

For the final mission, STS-135, we decided to bring a remote camera in addition to our regular photographic gear. This setup was designed to automatically take close-up shots of the shuttle on the launch pad, better than we could ever hope to capture from the media press site some three miles away.

Our biggest challenge was how to construct weatherproof housing for the camera (an old Canon EOS Digital Rebel XT) and a sound-activated trigger that would fire the camera's shutter once it picked up the roar from the shuttle's main engines. And we had to finish building and testing the system in less than two weeks. Talk about time pressure!

Fortunately, Joel Therrien, an electrical and computer engineering professor at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, volunteered to collaborate on the project, helping us design and build the electronic circuit for the sound trigger from scratch.

The trigger would have to be robust enough to withstand the shock wave from the shuttle's combined 6.5 million pounds of thrust, but not too sensitive that it would produce false triggers from thunderclaps or passing cars. And everything had to run on eight D cells that should last for at least 72 hours, in case of launch delays.

For the camera housing, we were inspired by the design of Charles A. Braswell Jr., a veteran launch photographer from Taylorsville, N.C., who uses regular toolboxes. So we picked up a plastic toolbox from a local Home Depot for less than $9, cut holes in the bottom for the camera lens and sound trigger, and mounted the whole unit on a sturdy, heavy-duty tripod.

We finished everything just two days before our flight to Florida. But when we tested the unit, the sound trigger wouldn't fire, even when we used our car's horn. (People must have wondered what we were doing in the parking lot!) Worse, something was draining the camera's battery completely in less than a half hour.

With one day to go before our departure, Joel had to redesign the circuit, modify the connection between the trigger and the camera, and adjust the trigger's sensitivity. It worked! That night, we disassembled the setup and hastily packed everything into a single suitcase.

Our biggest worry flying to Orlando — aside from flight delays or cancellations — was that our check-in baggage containing our tripods and accessories for the remote might get lost. Another concern was that airport-security screeners would confiscate the luggage after they saw wires, transistors, and battery holders inside the toolbox. (We initially wanted to add a digital timer to the circuit to help conserve battery power but decided it might attract too much attention.) Fortunately, everything went smoothly and we breathed a sigh of relief.

Since there were a lot of photographers who wanted to set up remote cameras on the eve of the launch, there was great demand for NASA vehicles and media escorts. Charles was able to arrange for a minivan that would take our group to the launch pad late that afternoon.

The swarm

It was close to 9 p.m. by the time we were able to set up our remote camera. We chose a spot called "the Mound," located southeast of Launch Complex 39A, just outside the perimeter fence.

Since we didn't expect to be setting up in the dark, we had no flashlight, so it was a challenge setting the camera controls. Adding to the misery was our constant battle against swarms of hungry mosquitoes that kept attacking us in all directions. They must have escaped from a secret science experiment — they really had a bad attitude!

Although we smothered ourselves and our clothing, the 25 percent DEET bug spray wasn't enough to keep the attackers from any piece of unprotected skin ? fingertips, lips, eyelids. We must have lost a pint of blood during the half hour it took us to finish the setup. Some big, mean-looking welts marked our arms, necks and faces by the time we were able to take cover inside the minivan.

During the ride back to the press site, we ran through the checklist in our mind. Had we remembered to attach all the cables securely? Put in the batteries properly? All we could do was hope and pray.

July fireworks

We had watched dozens of shuttle launches on TV and YouTube, but nothing beats the real thing. [10 Amazing Space Shuttle Photos]

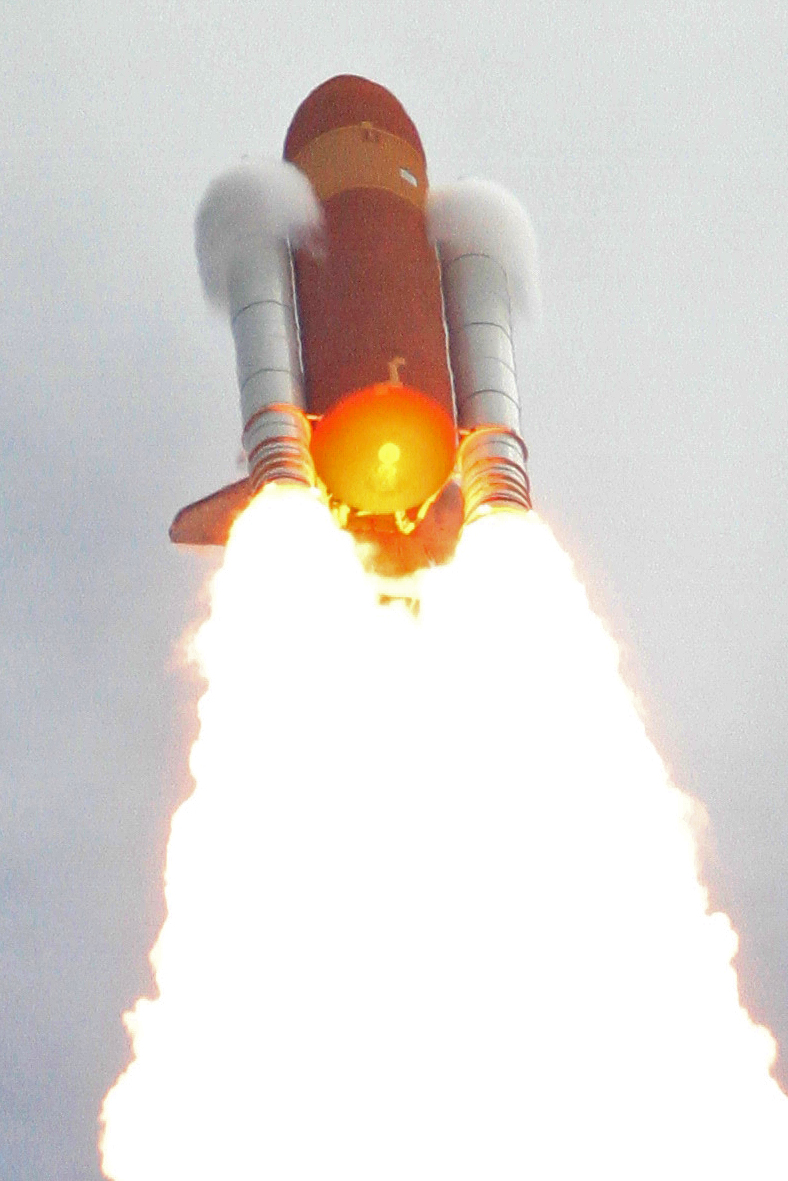

As smoke billowed above the treetops and Atlantis began its slow, majestic rise above the tower, we felt a rush of adrenaline through our veins. This was followed by a wave of pulsating pressure on our chests as the shuttle's acoustic energy reached our viewing site.

As the shuttle rose higher and faster, we were struck by how brilliant and magnificent the reddish orange plumes from the twin SRBs appeared through the cameras' viewfinders. They were blowtorches searing the hazy, humid morning sky. And it was hard to imagine that four brave souls, whom we had just seen board the NASA van earlier that day, were actually riding atop this immense pillar of fire.

With our cameras trained on the shuttle, we fired off several frames per second until Atlantis punched through the low-lying deck of clouds. Forty seconds after it left the launch pad for the final time, Atlantis was gone, but we could still hear the shuttle's rattling sound and follow the shadow cast by its contrail on the cloud deck. Squinting our eyes and craning our necks, we tried to catch one last glimpse of Atlantis in flight. Soon afterward, people cheered, hugged, shook hands and high-fived. Everyone had a big smile — Atlantis had just put on the most spectacular July fireworks of the year, and we had a ringside seat to it!

The end of an era

A couple of hours later that afternoon, after NASA determined that no rocket-exhaust residue had remained on the launch pad and it was safe to let people back in, we scrambled to retrieve our remote camera. It was a mad dash to cut the tripod loose from its anchor and grab the setup — those darn mosquitoes were still on the hunt, even in broad daylight.

Inside the SUV, we excitedly opened the camera housing and played back the camera's memory card. And there it was: In 63 frames the camera had captured the launch in all its raw power and glory — from main engine start to the time Atlantis cleared the tower and moved out of the camera's field of view. The sound trigger had worked flawlessly. We were ecstatic.

The final launch of Atlantis was profoundly bittersweet for us: Our first successful shuttle launch signaled the beginning of the end for the storied 3-decades-long shuttle program, a program marked by technological triumphs as well as tragic disasters. But for 40 seconds that hazy Friday morning, Atlantis was a sight to behold. It was a moment seared into our memory, and one that we will cherish for the rest of our lives.

Thank you, Atlantis!

Boston-based science journalists and photographers Imelda Joson and Edwin Aguirre have been following the shuttle program since 1981. Among their favorite movies are "The Right Stuff," "Apollo 13"and of course, "Space Camp."

Imelda B. Joson is a veteran astrophotographer, as well as an eclipse chaser and world traveler. With her husband, Edwin Aguirre, she has organized, led and/or participated in 11 solar eclipse expeditions in North America, Asia and Africa. The pair also conceptualized and created National Astronomy Week, an event that celebrates and publicizes astronomy in the Philippines.